Stalag Luft III facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stalag Luft III |

|

|---|---|

| German: Stammlager Luft | |

| Part of Luftwaffe | |

| Sagan, Lower Silesia, Nazi Germany (now Żagań, Poland) |

|

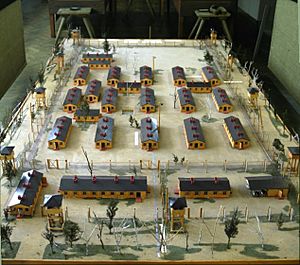

Model of the set used to film the movie The Great Escape. It depicts a smaller version of a single compound in Stalag Luft III. The model is now at the museum near where the prison camp was located.

|

|

| Coordinates | 51°35′55″N 15°18′27″E / 51.5986°N 15.3075°E |

| Type | Prisoner-of-war camp |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| In use | March 1942 – January 1945 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Events | The "Great Escape" |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders |

Oberst Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau |

| Occupants | Allied air crews |

Stalag Luft III was a special prison camp during World War II. It was run by the Luftwaffe, which was the German air force. This camp held captured airmen from the Allied countries.

The camp was built in March 1942 near a town called Sagan in what was then Nazi Germany. Today, this area is in Żagań, Poland. It was chosen because its sandy soil made it very hard for prisoners to dig escape tunnels.

Stalag Luft III is famous for two big escape plans by Allied prisoners. One happened in 1943 and inspired the movie The Wooden Horse (1950). The second, even more famous escape, was in March 1944. This was called the Great Escape. It was planned by Royal Air Force Squadron Leader Roger Bushell. A movie called The Great Escape (1963) was made about it.

The camp was freed by Soviet forces in January 1945. Today, the old camp site is a museum called the 'Stalag Luft III Prisoner Camp Museum'.

Contents

Life in the Camp: 1942–1944

The German military had a rule: each part of the military was in charge of prisoners from similar military branches. So, the Luftwaffe looked after captured Allied airmen. This included pilots from the British Fleet Air Arm. Sometimes, other non-air force people were also kept at Stalag Luft III.

Stammlager Luft meant "Main Camp, Air" in German. It was the Luftwaffe's name for a prisoner-of-war camp. At first, the camp only held officers. Later, more areas were added for non-commissioned officers (NCOs).

The first part of the camp, called the East Compound, opened in March 1942. The first prisoners, or kriegies (from the German word for "Prisoner of War"), were British and other Commonwealth officers. The Centre Compound opened in April 1942. It first held British NCOs, but by late 1942, American airmen took their place.

The North Compound, where the "Great Escape" happened, opened in March 1943 for British airmen. A South Compound for Americans opened in September 1943. By July 1944, a West Compound was also opened for US officers. Each area had fifteen small huts. Each bunkroom was about 10 by 12 feet and slept fifteen men in five triple-deck bunks.

The camp grew to about 60 acres. It held around 2,500 British officers and about 7,500 US airmen. There were also about 900 officers from other Allied air forces. In total, about 10,949 prisoners were held there.

Making Escape Hard

The prison camp had special features to make escaping very difficult. Digging tunnels was especially hard because of several things:

- The prisoner huts were raised about 60 centimeters (2 feet) off the ground. This made it easier for guards to spot any digging.

- The camp was built on very sandy soil. This loose sand made tunnels likely to collapse.

- The surface soil was dark grey, but the sand underneath was bright yellow. If prisoners brought the yellow sand to the surface, it would be easy for guards to see.

- Microphones were placed around the camp edges. These were meant to pick up any digging sounds.

Daily Life and Activities

Prisoners had a large library and school facilities. Many prisoners studied for degrees in subjects like languages, engineering, or law. The Red Cross provided exams, and academics who were also prisoners supervised them.

The prisoners also built a theater. They put on high-quality shows every two weeks. They even used the camp's sound system to broadcast a radio station called Station KRGY. They also published two newspapers, the Circuit and the Kriegie Times, four times a week.

Prisoners had a system to check new arrivals. This was to make sure no German spies got into their group. If a new prisoner couldn't be confirmed by two others, they were questioned closely. They were also watched by other prisoners until they were sure he was a real Allied prisoner. This method helped them find several spies.

The German guards were called "goons" by the prisoners. The guards didn't know what it meant and accepted the name. They were told it stood for "German Officer Or Non-Com." Prisoners watched the guards closely. They used a system of signals to warn others where the guards were. The guards' movements were written down in a logbook. The Germans couldn't stop this "Duty Pilot" system. Once, the camp commander even used the book to punish two guards who left their duty early.

The camp had about 800 Luftwaffe guards. They were either too old for fighting or recovering from injuries. Because they were air force personnel, the prisoners were treated better than other prisoners in Germany. The Deputy Commandant, Major Gustav Simoleit, was a former professor. He spoke many languages and was kind to the airmen. He even gave full military honors at funerals for Allied prisoners, including one for a Jewish airman.

Food was always a worry for the prisoners. A normal adult needs about 2,150 calories a day. The camp gave out German civilian rations, which were about 1,928 calories a day. The rest of the food came from Red Cross parcels from America, Canada, and Britain. Families also sent items to the prisoners. Red Cross parcels were shared equally among the men.

The camp also had a system for trading goods called a Foodacco. Prisoners could trade extra items for "points" to buy other things. German officers received a small amount of camp money (lagergeld). This money was used to buy goods from the German administration. Every three months, weak beer was sold in the canteen. All the camp money was put together for group purchases.

Stalag Luft III had the best sports program of any German POW camp. Each compound had sports fields and volleyball courts. Prisoners played basketball, softball, boxing, touch football, volleyball, table tennis, and fencing. They even had leagues for most sports. A large pool, used for fire-fighting water, was sometimes available for swimming.

Many of these activities were possible thanks to Henry Söderberg, a Swedish lawyer. He was a YMCA representative. He often brought sports equipment, religious items, and supplies for the camp's band, orchestra, and library.

The Famous Great Escape (1944)

Planning the Escape

In March 1943, Royal Air Force Squadron Leader Roger Bushell came up with a plan for a huge escape from the North Compound. He was in charge of the Escape Committee. Bushell, who had a legal background, presented his bold plan to the committee.

He told them, "Everyone here is living on borrowed time. We should all be dead! God gave us this extra life so we can make life hell for the Germans." He planned to focus all efforts on one main tunnel. No small, secret tunnels were allowed. Three very deep, very long tunnels would be dug: Tom, Dick, and Harry. He believed one would succeed!

Group Captain Herbert Massey, the senior British officer, approved the plan. Digging three tunnels at once was smart. If one was found, the guards wouldn't think two more were also being dug. The most daring part was the number of men. While past escapes involved up to 20 men, Bushell wanted over 200 to escape. They would wear civilian clothes and have fake papers. This escape was huge, so it needed amazing organization. Roger Bushell was known as "Big X." More than 600 prisoners helped dig the tunnels.

Digging the Tunnels

Three tunnels were dug for the escape: Tom, Dick, and Harry. The operation was so secret that everyone had to call each tunnel by its name. Bushell was very serious about this. He even threatened to punish anyone who said the word "tunnel."

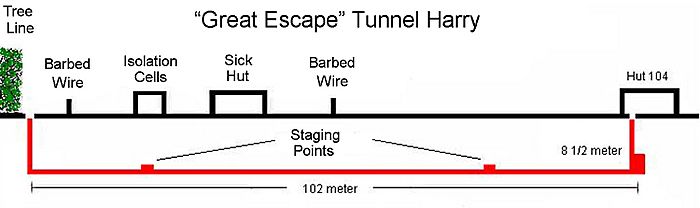

- Tom started in a dark corner of hut 123. It went west towards the forest. The Germans found it and blew it up.

- Dicks entrance was hidden in a drain in the washroom of hut 122. It had a very secure trap door. It was meant to go in the same direction as Tom. Prisoners thought this hut would not be suspected because it was further from the fence. Dick was later used to store soil and supplies. It also became a workshop.

- Harry started in hut 104. It went under the German administration area, the sick hut, and the isolation cells. It was planned to come out in the woods on the north side of the camp. The entrance to "Harry" was hidden under a stove. This tunnel was eventually used for the escape. It was discovered while the escape was happening. Only 76 of the planned 220 prisoners got out. The Germans filled it with sewage and sand, then sealed it with cement.

After the escape, the prisoners started digging another tunnel called George. But this tunnel was abandoned when the camp was emptied.

How the Tunnels Were Built

The tunnels were very deep, about 30 feet (9 meters) below the ground. They were also very small, only about 2 feet (0.6 meters) square. Larger rooms were dug for an air pump, a workshop, and resting spots. The sandy walls were held up with pieces of wood. Much of this wood came from the prisoners' beds. They used only about eight boards for each mattress instead of twenty. Other wooden furniture was also used.

Other materials were also used, like empty Klim powdered milk cans from the Red Cross. The metal from these cans was shaped into tools and lamps. The lamps burned fat skimmed from soup, with wicks made from old clothes. Klim cans were mostly used for the long air ducts in all three tunnels.

As the tunnels got longer, new ideas made the work easier and safer. Squadron Leader Bob Nelson invented a pump to push fresh air through the ducts. These pumps were made from bed pieces, hockey sticks, knapsacks, and Klim cans.

The usual way to get rid of the sand was to scatter it secretly on the ground. Prisoners made small pouches from towels or long underwear. They attached these inside their trousers. As they walked around, they could release the sand. Sometimes, they dumped sand into the small gardens they were allowed to tend. One prisoner would turn the soil while another released sand, making it look like they were just talking. Prisoners wore long coats to hide the sand bulges. They were called "penguins" because of how they looked. On sunny days, sand was carried out in blankets used for sunbathing. Over 200 blankets were used for about 25,000 trips.

The Germans knew something was happening but didn't find any tunnels for a long time. To stop an escape, nineteen main suspects were moved to another camp. Only six of them had actually worked on the tunnels. One of them, a Canadian named Wally Floody, was in charge of digging and camouflage.

Eventually, prisoners couldn't hide sand above ground anymore. Snow also made it impossible to scatter sand without being seen. After "Dick"'s planned exit was covered by a new camp building, they decided to fill it up. Since "Dick"'s entrance was well hidden, it was also used to store maps, stamps, fake travel permits, compasses, and clothes. Some guards helped by giving them train timetables, maps, and official papers to forge. Some real civilian clothes were bought by bribing German staff with cigarettes, coffee, or chocolate. These were used by escapees to travel more easily, especially by train.

The prisoners ran out of places to hide sand. There was a large empty space under the theater seats. When the theater was built, the prisoners had promised not to misuse the materials. But after discussing it, the senior British officers decided that the finished building was not part of that promise. A seat in the back row was hinged, and the sand problem was solved.

More American prisoners started arriving. The Germans decided to build new camps just for US airmen. To help as many people escape as possible, including Americans, work on the remaining two tunnels sped up. This drew attention from guards. In September 1943, the entrance to "Tom" was found. Guards in the woods saw sand being removed from the hut. Work on "Harry" stopped until January 1944.

The Great Escape Begins

"Harry" was finally ready in March 1944. By then, most Americans had been moved. Only one American, Major Johnnie Dodge, who had become a British citizen, took part in the "Great Escape." The escape was planned for summer because of good weather. But in early 1944, the Gestapo (German secret police) visited the camp. They ordered more effort to find escapes. Rather than risk waiting and having their tunnel found, Bushell ordered the escape to happen as soon as "Harry" was ready.

Many Germans helped the escape in small ways. The movie suggests that forgers could make perfect copies of any German pass. In reality, the forgers got a lot of help from Germans who lived far away. Several German guards, who didn't support the Nazis, also willingly gave prisoners items and help.

Out of the 600 who worked on the tunnels, only 200 were planned to escape. Prisoners were split into two groups. The first group of 100, called "serial offenders," were guaranteed a spot. This included 30 who spoke good German or had escaped before, and 70 who had worked the most on the tunnels. The second group, chosen by drawing lots, had less chance of success. They were called "hard-arsers." They would have to travel at night because they spoke little German and had only basic fake papers.

The prisoners waited for a night with no moon. On Friday, March 24, the escape began. As night fell, those chosen went to Hut 104. The exit trap door of Harry was frozen solid, which delayed the escape by an hour and a half. Then, they found the tunnel was too short of the forest. At 10:30 p.m., the first man came out just before the tree line, near a guard tower. The temperature was below freezing, and there was snow. Crawling to cover would leave a dark trail. To avoid being seen, escapes slowed to about ten per hour, instead of one every minute. Word was sent back that no one with a number above 100 would get out before daylight. These men changed back into their uniforms and got some sleep. An air raid then turned off the camp's lights, slowing the escape even more. Around 1 a.m., the tunnel collapsed and had to be fixed.

Despite these problems, 76 men crawled to freedom. But at 4:55 a.m. on March 25, the 77th man was spotted by a guard. Those already in the trees started running. New Zealand Squadron Leader Leonard Henry Trent VC, who had just reached the tree line, stood up and surrendered. The guards didn't know where the tunnel entrance was. They started searching the huts, giving men time to burn their fake papers. Hut 104 was one of the last to be searched. Even with dogs, the guards couldn't find the entrance. Finally, German guard Charlie Pilz crawled back through the tunnel but got stuck at the camp end. He called for help, and the prisoners opened the entrance to let him out, finally showing its location.

An early problem for the escapees was finding the railway station. Daylight showed it was in a hidden part of an underground tunnel. Many missed their night trains. They decided to walk or wait on the platform in daylight. Another problem was that it was the coldest March in thirty years, with snow up to 5 feet (1.5 meters) deep. Escapees had to leave the cover of woods and fields and stay on the roads.

The Fate of the Escapees

After the escape, the Germans checked the camp. They found out how much work had gone into the escape. Four thousand bed boards were missing, along with many other items like beds, mattresses, tables, chairs, and tools. Electric cable was also stolen. German workers who didn't report the theft were punished. After this, each bed only had nine bed boards, which guards counted regularly.

Of the 76 escapees, 73 were caught. Adolf Hitler first wanted all recaptured officers to be shot. But other German leaders told him this might lead to revenge against German pilots held by the Allies. Hitler agreed, but still ordered that "more than half" be shot. He told SS head Heinrich Himmler to execute more than half of them. Himmler passed this order to General Arthur Nebe. Fifty of the escapees were killed, one or two at a time. Roger Bushell, the escape leader, was shot by a Gestapo official. Bob Nelson was likely spared because they thought he was related to Admiral Nelson. Dick Churchill was probably spared because of his last name, which was the same as the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Seventeen captured escapees were sent back to Stalag Luft III. Four others were sent to a high-security prison at Colditz Castle or Sachsenhausen concentration camp. They managed to tunnel out and escape again from Sachsenhausen three months later, but were recaptured.

Only three escapees made it to freedom:

- Per Bergsland, a Norwegian pilot.

- Jens Müller, another Norwegian pilot.

- Bram van der Stok, a Dutch pilot.

Bergsland and Müller escaped together. They reached neutral Sweden by train and boat with help from Swedish sailors. Van der Stok, who was good with languages and escaping, traveled through occupied Europe. He got help from the French Resistance and found safety at a British consulate in Spain.

After the Escape

The Gestapo investigated the escape. The camp commander, Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau, was removed from his post. He was later wounded by Soviet troops. He surrendered to British forces and was a prisoner for two years. He testified during the investigation into the killings. He had followed the rules for treating prisoners and was respected by the senior prisoners.

On April 6, 1944, the new camp commander, Oberstleutnant Erich Cordes, told the prisoners that 41 escapees had been shot while resisting arrest. The British government learned of the deaths in May. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden announced the news to the House of Commons. He promised that those responsible would face justice after the war.

After the war, an investigation began. Several former Gestapo and military personnel were found responsible for killing escapees. They were punished for their actions.

In 1964, the West German government agreed to pay money to British victims of Nazism, including survivors of the Stalag Luft III escape.

Notable Former Prisoners

Many people held at Stalag Luft III went on to have interesting careers.

- Paul Brickhill, an Australian journalist, wrote The Great Escape, the first full story of the breakout. This book was later made into the famous movie.

- Wally Floody, a Canadian pilot, was in charge of digging and camouflage for the tunnels. He was moved from the camp before the Great Escape, which saved his life. He later became a technical adviser for The Great Escape movie. He is thought to be the real-life person behind the "Tunnel King" character in the film.

- Peter Butterworth, a British actor, was a prisoner. He was one of the men who did gymnastics over the tunnel entrance for the "Wooden Horse" escape. He later became famous for his roles in the Carry On films.

- Rupert Davies, a British actor, performed in plays at the camp theater. He later became well-known for playing Inspector Maigret on TV.

- Cy Grant, a British singer, actor, and author, was a prisoner for two years. He was the first black person to regularly appear on British television, singing the news in a "topical calypso" style.

- Phil Marchildon, a Major League Baseball pitcher, spent nine months in the camp. He continued his baseball career after the war.

- Ray Rayner, an American children's television personality, was also a prisoner in the camp.

- Justin O'Byrne, an Australian, spent over three years as a prisoner. He later served in the Australian Senate for 34 years and became its President.

- Anthony Barber, who later became Lord Barber, was a British politician. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1970 to 1974.

Leaving the Camp in 1945

Just before midnight on January 27, 1945, Soviet troops were only 16 miles (26 km) away. The remaining 11,000 prisoners were forced to march out of the camp. Their destination was Spremberg. In freezing temperatures and 6 inches (15 cm) of snow, 2,000 prisoners had to clear the road. After a 34-mile (55 km) march, they reached Bad Muskau and rested for 30 hours. Then they marched another 16 miles (26 km) to Spremberg.

On January 31, some prisoners were sent by train to Stalag VII-A at Moosburg. More followed on February 7. Thirty-two prisoners escaped during the march to Moosburg, but all were caught again. Other prisoners from Spremberg were sent to Stalag XIII-D at Nürnberg on February 2.

As US forces got closer on April 13, the American prisoners at XIII-D were marched to Stalag VII-A. Most reached VII-A on April 20. Many dropped out along the way, and the German guards did not try to stop them. Stalag VII-A was built for 14,000 prisoners, but now held 130,000 from other camps. Many lived in tents or air raid trenches. The US 14th Armored Division freed the prisoners of VII-A on April 29.

|