Stephen and Harriet Myers House facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence

|

|

North (front) elevation, 2015

|

|

| Location | Albany, NY |

|---|---|

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1847 |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 04000999 |

| Added to NRHP | November 30, 2004 |

The Stephen and Harriet Myers Residence is a historic house in Albany, New York. It was built in the mid-1800s in the Greek Revival style. This building is special because it was a key spot on the Underground Railroad.

In 2004, the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places. It is also part of the New York State Underground Railroad Heritage Trail. The National Park Service also recognizes it as a site on its National Network to Freedom.

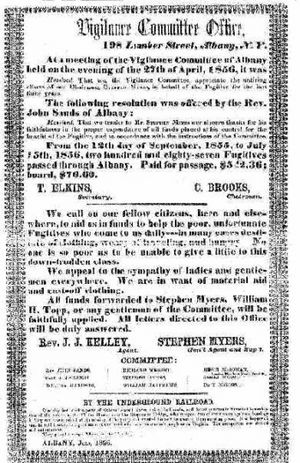

Stephen Myers was freed from slavery when he was young. He became a leader in the Vigilance Committee of Albany. This group helped people escape slavery. Stephen and his wife, Harriet, helped many people for almost 30 years.

Stephen also wrote for abolitionist newspapers. He even spoke with famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He worked hard to make life better for the African American community in Albany. He helped start one of the first schools for them in the city.

The house was almost torn down in the 1970s. Luckily, it was saved. Now, the Underground Railroad History Project of the Capital Region is working to restore it. They are using money from both public and private sources.

Contents

What Does the Myers Residence Look Like?

The Myers Residence is on Livingston Avenue in Albany's Arbor Hill neighborhood. This area is north of downtown Albany. The house is one of the few brick buildings on its street. It stands among older wooden buildings.

The land slopes down towards the Hudson River to the east. To the west, the ground is flat. Nearby is the Arbor Hill Historic District–Ten Broeck Triangle. This area is also listed on the National Register. The Ten Broeck Mansion is also in this historic district.

Outside the House

The house has 2+1⁄2 stories and is made of brick. It has three sections, called bays, and an exposed basement. Wooden steps lead up to the main front door. There are no windows on the sides of the house. The back of the house is currently covered with asphalt shingles. However, during restoration, the original brick will be seen again.

The house has special stone trim. This trim is made of sandstone. The window frames and sills are plain and rectangular. The main entrance has a triangular stone above it. The first-floor windows have their original six-over-six panes. Upstairs, only the western window has its original panes. The others will be restored to match. There are also small windows in the basement and attic. All these older parts will be restored.

Inside the House

The main entrance is set back a little. Many of its original decorations are gone. It currently has a modern door with clear panels.

Below the steps is the basement entrance. It opens into a long hallway. At the front, there is a large room. This was probably the dining room. Most of the inside decorations are worn out. But, the original wooden panels on the walls and a wooden fireplace mantel are still there. The fireplace opening is closed off with bricks.

At the back of the hall, the stairs begin. There is a newel post at the bottom of the stairs. However, the railing is missing. The stairs turn 180 degrees. The windows on the stairwell are a bit lower than other windows on the same floor.

The first floor has a similar layout. The ceilings in the front rooms, called parlors, are higher. These rooms also have plaster decorations on the ceilings. The fireplace areas have lost their original plaster. But the window frames, wall panels below the windows, and flooring are all original.

The second floor has the same layout. There is a small room at the front of the hallway. The bedrooms have their original wooden trim. However, they do not have fireplaces. There are small closets on either side of the fireplace area in the back room.

The attic has two main sections. The front room is divided into a large and small room. Some original wooden trim remains, even with the modern wall panels.

The Story of Stephen Myers

The history of the Myers house is mostly about Stephen Myers. He did not own the house. But he was its second and most famous resident. He made it a very important stop on the Underground Railroad.

Stephen Myers' Early Life (1800–1846)

Stephen Myers was born into slavery around 1800. This was near Hoosick, northeast of Albany. Some records say he was freed by General Warren in 1818. However, details about this are not clear.

For the next ten years, he worked in different jobs. These included being a grocer and a steamboat worker. In 1827, he married Harriet Johnson in Troy. They had four children together.

Myers began helping people escape slavery in 1831. He was also very active in Albany's African American community. Many members of this community lived in Arbor Hill. They often lived in neighborhoods with people of all races.

Myers believed in the importance of work and education. He raised money for these causes himself. One of his supporters was John Clarkson Jay, the grandson of John Jay. A historian says Myers helped start the first African-American school in Albany. Myers was the first leader of the school at the Methodist Episcopal Church.

He also worked to get better voting rights for African Americans. He started the Albany Suffrage Club. He was also president of the New York State Suffrage Association. He spoke directly with state lawmakers. He also spoke out against using public money to send freed slaves to Africa.

Myers started his first newspaper, The Elevator, for a short time. Later, he joined the Northern Star Association. This group helped people escaping slavery. They also published a newspaper called The Northern Star and Freemen's Advocate. Myers wrote many articles for this paper. They spoke out against slavery and supported temperance (avoiding alcohol). They also promoted African American self-help, education, and jobs.

The Northern Star Association was at first a rival to Albany's older Vigilance Committee. The Vigilance Committee had a wider group of members. These included established African American families and religious groups against slavery. They also published a newspaper called the Tocsin of Liberty.

The two groups sometimes criticized each other. They argued about who was doing a better job helping people escape slavery. At one point, the Tocsin accused Myers of keeping money meant for the committee. But he had only accepted it for his own association.

In the mid-1840s, the groups became more friendly. This happened after two important clergymen from the Vigilance Committee died. One died from pneumonia while speaking against slavery. The other, Charles Torrey, died in prison in Maryland. He had been arrested for helping escaped slaves. After this, the two groups joined together. Stephen Myers became the leader of the larger Vigilance Committee.

From this new role, Myers became well-known in the abolition movement. He continued to publish The Northern Star. He also spoke at anti-slavery events. Sometimes he shared the stage with Frederick Douglass. Douglass later said Myers was very important to the Underground Railroad. From the Myers' house, people escaping slavery were sent west. They eventually crossed into Canada to find freedom.

Building the House (1847)

In 1847, John Johnson built the house at what was then 198 Lumber Street. John Johnson was an African American boat captain. He owned a boat called the Miriam. The neighborhood was mostly working class. Many people worked on the boats or docks. City records show an Abram Johnson living nearby. The 1855 Census shows John was Abram's son. Harriet, who married Stephen Myers, was Abram's daughter.

John Johnson owned the house. It is not known how Stephen Myers and his family lived there. No architect is known for the house. It seems to have been a typical Albany rowhouse of that time.

Later Life and Activism (1848–1870s)

Two years after moving into the new house, in 1849, Myers combined his newspaper, The Northern Star, with another paper. This was The True American, published by Samuel Ringgold Ward. The new paper was called The Impartial Citizen. It was published from Syracuse. But it only lasted two more years before going out of business.

The 1850s were hard for anti-slavery activists. This was because of the new Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law made it harder to help people escape slavery. It also increased punishments for those who helped. Myers started another newspaper, The Telegraph and Journal. But he closed it in 1855. He asked his readers to subscribe to Douglass's newspaper instead.

In 1850, Myers was elected to a committee for the American League of Colored Laborers. This showed his continued work beyond just ending slavery. Two years later, he stepped down as head of the Vigilance Committee. But he kept working for the Underground Railroad. In 1856, the Vigilance Committee honored him. They said he had helped 287 people escape in less than a year. A historian later wrote that Myers' house was "the best-run part of the Underground Railroad in the state."

Paul Stewart, a historian, says the Myers family was very open about their work. They were welcoming to the people escaping slavery. "When you say Underground Railroad, you think of a lot of secrecy," he said. "But the closer you look at things, the more you learn. They entertained people at their dinner table. They probably had them sleeping in the upstairs bedroom. It's not like they were hiding them in the basement." Myers sent many people to Syracuse or Oswego. Some went directly north to Canada. They often traveled by steamboat on Lake Champlain.

Without his newspapers, Myers needed other work. In August 1860, he worked as a butler in Lake George. Back in Albany, Harriet kept the station running. She wrote that she helped ten people escape that month. By the end of the year, Stephen said he had helped more people in two months than in any four-month period before.

This was because the American Civil War was about to begin. Myers remained active during the war. He organized celebrations for the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. He also helped recruit soldiers for the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. This was a black unit raised by Massachusetts.

After the Union won the war in 1865, Harriet Myers died. Her obituary mentioned her help in assisting those escaping slavery. It also noted her support for her husband's newspapers. Five years later, Stephen died. The Albany Evening Times said he had been working as a janitor. They claimed he "did more for his people than any other colored man living." He is buried in Albany Rural Cemetery.

Restoring the House (1871–Present)

After the Myers family, other people owned the house. It stayed mostly the same. The house next door was replaced in 1872.

By the mid-1900s, the house was empty and falling apart. Many houses in the Arbor Hill neighborhood were torn down. This was part of a city plan in 1962. But the Myers house and some older houses nearby were saved.

However, the house continued to be neglected. By the 2000s, the county owned it because of unpaid taxes. Local historian Paul Stewart and his wife, Mary Liz, learned about Myers. They started the Underground Railroad History Project of the Capital Region. They began holding a yearly meeting about slavery in 2001.

The group bought the house from the county in 2004 for $1,500. For several years, they raised money to restore the house. Their goal is to make it a historic house museum. It will teach people about Myers and the local Underground Railroad. The state gave them a $50,000 grant at first. By 2007, they had raised over half a million dollars. Four years later, the state gave them another $350,000 grant. The group hopes to finish the restoration and open the house to the public soon.

Images for kids

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |