Sue Bailey Thurman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sue Bailey Thurman

|

|

|---|---|

Sue Bailey Thurman, 1953

|

|

| Born |

Sue Elvie Bailey

August 26, 1903 |

| Died | December 25, 1996 (aged 93) San Francisco, California

|

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | writer, lecturer, historian, civil rights activist |

| Years active | 1926–95 |

Sue Bailey Thurman (born Sue Elvie Bailey; August 26, 1903 – December 25, 1996) was an American writer, speaker, historian, and a champion for equal rights. She made history as the first non-white student to get a music degree from Oberlin College in Ohio.

After teaching for a short time, she started working internationally with the YWCA in 1930. On a trip to Asia in the 1930s, Sue Bailey Thurman became the first African-American woman to meet Mahatma Gandhi. This meeting inspired her and her husband, Howard Thurman, to spread the idea of peaceful protest to bring about change. They shared these ideas with a young preacher, Martin Luther King Jr..

Even though they didn't join protests, the Thurmans helped many people involved in the Civil Rights Movement by offering spiritual guidance. They also helped start the first church in the United States that welcomed people of all races and beliefs.

Thurman worked to create international student groups. These groups helped students from other countries feel less alone while studying abroad. She also started one of the first scholarship programs for African-American women to study overseas. She studied how racism and unfair treatment affected people around the world. She even traveled around the world twice!

To preserve black history, she wrote books and newspaper articles. She also helped the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) start publishing by creating the Aframerican Women's Journal. In 1958, she published a cookbook that also shared stories about black professional women. This was important because, at the time, black Americans had few civil rights. Thurman used the idea of food to share the lives of black women who were not just domestic workers. She also attended international meetings about peace and women's rights. In 1945, she was part of a special group at the meeting to create the United Nations. Thurman also founded museums, like the Museum of Afro-American History in Boston in 1963.

Thurman and her husband retired in San Francisco in 1965. She worked with the San Francisco Public Library in 1969 to create resources about black history in the American West. In 1979, she received an award from Spelman College. After her husband passed away in 1981, Thurman managed the Howard Thurman Educational Trust. This trust supported research and helped black students with scholarships. When she died in 1996, she left their large collection of historical papers to many universities.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Sue Elvie Bailey was born on August 26, 1903, in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Her parents were Reverend Isaac and Susie Bailey. She went to primary school at Nannie Burroughs' School for Girls in Washington, D.C.

In 1920, she finished high school at Spelman Seminary, which is now Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia. She then went to Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio. In 1926, she graduated with degrees in music and liberal arts. This made her the first black student to earn a music degree from Oberlin.

While at Oberlin, Sue became friends with Louise Thompson. Louise later became important in the Harlem Renaissance movement. Sue also encouraged Langston Hughes, a famous poet, to read his jazz poetry there. Sue traveled with a music group, performing concerts in cities like Cleveland, New York, and Philadelphia, as well as London and Paris.

Starting Her Career

After college, Thurman became a music teacher at the Hampton Institute in Virginia. However, she didn't enjoy the job much. Her friend, Louise Thompson, who also taught there, had secretly written to W. E. B. Du Bois. He was a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Louise complained about the college's management, which was mostly white.

Even though Sue was suspected of writing the letter, she didn't tell on Louise. Instead, she invited Langston Hughes to Hampton to give a poetry reading and offer support. In 1930, Sue left Hampton to become a traveling National Secretary for the Student Division of the YWCA. She gave talks across Europe and helped create the first World Fellowship Committee for the YWCA.

On June 12, 1932, Sue Bailey married Howard Thurman (1900–1981) in Kings Mountain, North Carolina. Howard was a minister, writer, and later became a dean at several major U.S. universities. At the time they married, he was a dean and professor at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Journey to Asia

In 1935, Sue and Howard Thurman went on a six-month trip through southern Asia. They visited Burma, Ceylon, and India. The trip ended with a "Pilgrimage of Friendship" to an International Student Conference in India. Howard led the American group and gave talks at over forty universities.

Sue was asked to meet with reporters and students. She discussed race relations and compared the situation of Indians under British rule to that of African Americans in the U.S. Howard had first turned down the trip, and Sue was not included in the original offer. But when the trip was finally agreed upon, both of them participated. The committee chose Sue not just as Howard's wife, but because she was one of "four persons best able to do this particular job." This was special for the time, as black women were often overlooked in important social roles.

During the trip, Thurman gave talks about black women and their organizations. She also spoke about international cooperation and culture. When they met Rabindranath Tagore in Santiniketan, she presented a paper called "The History of Negro Music." She also sang and taught songs to local choirs. She even shared her knowledge about art, which she had learned on an earlier trip to Mexico.

The Thurmans met with Mahatma Gandhi, becoming the first African Americans to have a meeting with him. When Thurman asked him to bring his message to the United States, he said his work in India was not yet finished. A key part of their meeting was discussing how peaceful resistance could lead to social change. This meeting deeply affected the Thurmans, changing their lives.

Even though they remained Christians, meeting Gandhi made them think about starting a church free from prejudice. They wanted a church that would go beyond racial, social, economic, and spiritual differences. After they returned to the U.S., Howard decided to take on the challenge of founding such a church in San Francisco. Sue went with him, bringing their two daughters, because she strongly believed in this cause.

Important Work in the Mid-Career Years

Helping Students and Preserving History

In the late 1930s, Thurman started the Juliette Derricotte Scholarship. This scholarship helped African-American undergraduate women with excellent grades study and travel abroad. The first two students to receive this scholarship were Marian Banfield and Anna V. Brown.

In 1940, Thurman founded the Aframerican Women's Journal. This was the first magazine published by the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). She edited it from 1940 to 1944. In 1941, a committee was formed to collect writings about the achievements of African-American women. In 1944, Thurman became the head of this committee. Her mother donated $1,000 to help create the National Council of Negro Women's National Library, Archives, and Museum. On June 30, 1946, they held a drive to collect photos, books, and mementos. They opened the first part of the library at what is now the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

In 1943, Thurman and her husband moved to San Francisco. She wrote several articles about their trip to Asia. She shared information, discussed their meeting with Gandhi, and pushed for student exchange programs for black students at Indian universities. It was from the Thurmans' talks and writings that Martin Luther King Jr. learned about peaceful resistance as a way to protest.

By 1944, the church they had dreamed of after meeting Gandhi became real. They, along with Fisk, opened the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples. It was the first church in the United States that welcomed people of all races and beliefs. While her husband was the pastor, Thurman organized discussions and talks. These events helped members learn about other cultures, like Native Americans, Africans, and Asians.

In 1945, Thurman attended the San Francisco Conference where the United Nations was founded. She was part of a special group of observers. The official African-American group included important leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois and Mary McLeod Bethune. Bethune insisted on sending three more observers from the NCNW, and Thurman was one of them. After the event, Thurman wrote a report where she questioned why people of color had such a small role in the meetings. She pointed out that the large populations in developing countries would become very important.

In 1947, Thurman attended a women's conference in Guatemala City, Guatemala. This meeting discussed many issues she cared about, such as women's rights, international cooperation, and peace. In 1949, she led a group from her church to Paris for a meeting of UNESCO.

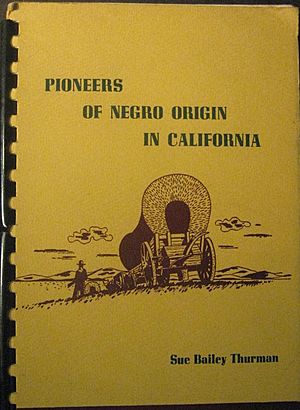

After researching black history in California, Thurman wrote eight articles for a newspaper series called "Pioneers of Negro Origin in California." In 1952, she published these articles as a book with the same title. This was the second history of black Californians ever published. It helped fill a gap because, at the time, academic history in America mostly focused on white men.

Life in Boston

In 1953, Howard Thurman became the Dean of the Boston University School of Theology. After ten years in California, the couple moved to Boston. They wanted to share their ideas of welcoming everyone in a university setting. They knew it would be challenging for the first black pastor to work in a white university. From the start, Thurman worked to create a welcoming environment. She organized monthly dinners for the Marsh Chapel Choir members and their friends.

Thurman also started the International Student Hostess Committee. This committee helped international students feel less alone. By 1965, the committee was helping 500 international students at Boston University. Some people criticized the Thurmans for not being more active in the Civil Rights Movement. However, they believed their role was to support the spiritual needs of those who were actively protesting. Many letters from civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. himself, thanked the Thurmans for their spiritual guidance.

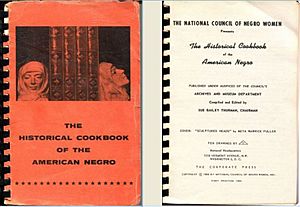

Thurman continued her writing in Boston. In 1958, she published The Historical Cookbook of the American Negro. This book not only had recipes but also included black history. It shared stories of professional black women to challenge the idea that all black women were maids. She knew that to tell their history, she needed a new way, as there wasn't a big market for African-American histories. In her book's introduction, she called it "palatable history," showing her clever marketing skills.

During the 1960s, the Thurmans traveled widely to study how racial barriers prevented communities from forming. A two-year break from Boston University made these travels possible. In 1962, they went to Saskatchewan, Canada, to meet with tribal leaders about discrimination. In 1963, they traveled to Nigeria, Israel, Hawaii, and California. In Nigeria, Howard Thurman lectured at the University of Ibadan. The couple's second trip around the world took them to Japan, the Philippines, and Egypt.

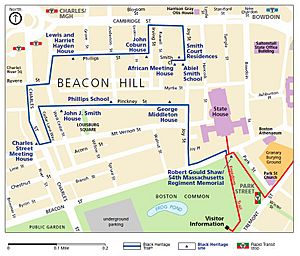

In 1963, Thurman founded the Museum of Afro-American History in Boston. She was very interested in history. She found a place where free black people had lived before the Civil War. She also found their 1808 African Meeting House, which was Boston's first black church and the first segregated public school. The museum was created to save this site and buy other important properties to preserve African-American heritage.

Thurman also created a map of important African-American historical sites in Boston with her daughter, Anne Chiarenza. She called it "Negro Freedom Trails of Boston." The map highlighted twenty-two places important to black history in the city. It was partly created to help black schoolchildren feel they were part of the city's history. What is now known as the Black Heritage Trail was inspired by Thurman's original idea.

While in Boston in 1962, Thurman arranged for the sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller to create a "freedom plaque" for Livingstone College. In 1963, Thurman was a guest speaker at Livingstone. To celebrate United Nations Day, she donated a collection of dolls representing the member nations to the college. Since the 1930s, Thurman had collected dolls from different cultures and given them to universities to help people understand cultural differences. In 1967, Livingstone College gave her an honorary doctorate degree.

Return to San Francisco

Howard Thurman retired from Boston University in 1965, and the couple moved back to San Francisco. Thurman continued her work in preserving history. In 1969, she worked with the San Francisco Public Library to develop resources about black history in the American West. In the 1970s, the couple traveled to the Pacific region. In 1979, she received a special award at Spelman College. She shared this honor with UNESCO director Herschelle Sullivan Challenor.

After her husband's death in 1981, Thurman took over managing the Howard Thurman Educational Trust. This trust supported research for literary, religious, and scientific purposes. It also provided scholarships for black students and helped charitable projects. Thurman was the mother of Anne Spencer Thurman and stepmother to Olive Thurman, her husband's daughter from his first marriage.

Sue Bailey Thurman passed away on Christmas Day, 1996, at the San Francisco Zen Buddhist Hospice Center.

Her Lasting Impact

After her death in 1996, Sue and Howard Thurman's large collections of documents and writings were donated to many universities, as they had wished. The biggest collection of their papers is at Boston University. Other collections are at Oberlin, Emory University, and other places. These include the National Council of Negro Women's archives in Washington, D.C., and libraries in Arkansas named after her mother, Mrs. Susie Ford Bailey. The collection at Emory University includes letters between the Thurmans and Mrs. Bailey, their personal libraries, and nearly one thousand photographs.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |