Tenerife airport disaster facts for kids

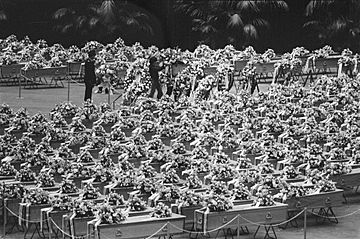

Wreckage of the KLM aircraft on the runway at Los Rodeos

|

|

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | March 27, 1977 |

| Summary | Runway collision |

| Place |

28°28′53.94″N 16°20′18.24″W / 28.4816500°N 16.3384000°W |

| Total injuries (non-fatal) | 61 |

| Total fatalities | 583 |

| Total survivors | 61 |

| First aircraft | |

PH-BUF, the KLM Boeing 747-206B involved in the accident |

|

| Type | Boeing 747-206B |

| Name | Rijn ("Rhine") |

| Airline/user | KLM Royal Dutch Airlines |

| Registration | PH-BUF |

| Flew from | Amsterdam Airport Schiphol Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Flying to | Gran Canaria Airport Gran Canaria, Canary Islands |

| Passengers | 234 |

| Crew | 14 |

| Fatalities | 248 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Second aircraft | |

N736PA, the Pan Am Boeing 747-121 involved in the accident |

|

| Type | Boeing 747-121 |

| Name | Clipper Victor |

| Airline/user | Pan American World Airways |

| Registration | N736PA |

| Flew from | Los Angeles International Airport Los Angeles, United States |

| Stopover | John F. Kennedy International Airport, New York City, U.S. |

| Flying to | Gran Canaria Airport Gran Canaria, Canary Islands |

| Passengers | 380 |

| Crew | 16 |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 61 |

| Fatalities | 335 |

| Survivors | 61 |

The Tenerife airport disaster happened on March 27, 1977. Two large Boeing 747 passenger planes crashed on the runway at Los Rodeos Airport in Tenerife, Spain. This airport is now called Tenerife North Airport.

The crash happened when KLM Flight 4805 started its takeoff in thick fog. At the same time, Pan Am Flight 1736 was still on the same runway. The planes crashed into each other. Everyone on the KLM plane died. Most people on the Pan Am plane also died. Only 61 people survived from the front part of the Pan Am plane.

This accident was the worst aviation disaster in Spain. With 583 people killed, it is also the deadliest accident in aviation history.

Contents

What Caused the Disaster?

A bomb had gone off at Gran Canaria Airport. This caused many flights, including the two planes that crashed, to be sent to Los Rodeos. The airport quickly became very crowded. Parked planes blocked the main taxiway. This meant planes had to use the runway to move around.

Thick fog also started to cover the airport. This made it very hard for pilots and the control tower to see.

Spanish investigators later said the main reason for the crash was the KLM captain's decision to take off. He wrongly believed he had permission from air traffic control (ATC). Dutch investigators also pointed to misunderstandings in radio talks. KLM later accepted that their crew was responsible. They agreed to pay money to the families of the victims.

This disaster changed how the airline industry works. It showed how important it is to use clear, standard words in radio messages. Rules for how pilots work together in the cockpit also changed. This led to a new way of training pilots called crew resource management. Now, pilots are encouraged to work as a team. The captain is not the only one making decisions.

People Affected

Both planes were completely destroyed in the crash. All 248 people on the KLM plane died. This included passengers and crew. On the Pan Am plane, 335 people died. This was mainly because of the fire and explosions from the fuel.

Sixty-one people on the Pan Am plane survived. At first, 70 people survived, but 9 later died from their injuries. The captain, first officer, and flight engineer of the Pan Am plane were among the survivors. Most survivors got out by walking onto the left wing of the plane. This was the side away from the crash. They found holes in the plane's body to escape.

The Pan Am's engines kept running for a few minutes after the crash. The top part of the cockpit, where the engine controls were, was destroyed. This meant the crew could not turn off the engines. Survivors waited for help. But firefighters first thought there was only one plane involved. They focused on the KLM wreckage far away in the fog. Eventually, most survivors on the wing dropped to the ground.

Notable People Who Died

- Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten: He was a chief flight instructor for KLM. He was also the captain of the KLM flight.

- Eve Meyer: She was a model and actress. She was on the Pan Am flight.

- A. P. Hamann: He was a former city manager of San Jose, California. He was on the Pan Am flight.

What Happened After

The day after the crash, the Canary Islands Independence Movement said they were not responsible for the accident. This group had set off the bomb at Gran Canaria Airport earlier.

Los Rodeos Airport was closed to all planes for two days. The first investigators arrived by boat from Las Palmas. A U.S. Air Force C-130 transport plane was the first aircraft to land. It landed on the airport's main taxiway on March 29. This plane helped transport injured survivors to hospitals.

Spanish Army soldiers cleared the wreckage from the runways. By March 30, small planes could use the airport again. Large jets could not land yet. Los Rodeos fully reopened on April 3. This was after all wreckage was removed and repairs were done.

The Investigation

Spain's Civil Aviation Accident and Incident Investigation Commission (CIAIAC) investigated the accident. About 70 people helped with the investigation. This included experts from the United States, the Netherlands, and both airlines. They found that there were misunderstandings before the crash.

Recordings from the cockpit showed the KLM pilot thought he was cleared for takeoff. But the control tower thought the KLM plane was still waiting at the end of the runway.

Main Cause of the Crash

The investigation concluded that the main cause was the KLM captain, Veldhuyzen van Zanten. He tried to take off without permission. Investigators thought he wanted to leave quickly. This was to meet KLM's rules about how long pilots could work. He also wanted to leave before the weather got worse.

Other big reasons for the accident were:

- The sudden fog made it very hard to see. The control tower and both crews could not see each other.

- Other radio messages made it hard to hear important instructions.

Some other factors contributed but were not the main cause:

- The KLM co-pilot and the control tower used unclear words. For example, "We're at take off" and "OK."

- The Pan Am plane did not leave the runway at the correct exit.

- The airport was very crowded because of the bomb threat. This changed how taxiways were normally used.

What Else Was Considered

This was one of the first investigations to look at "human factors." These included:

- Captain Veldhuyzen van Zanten had not flown regular routes for 12 weeks. He was a training captain and mostly worked on simulators.

- The KLM crew was worried about working too many hours. Dutch law had recently made these rules stricter. This might have made the captain want to refuel quickly at Tenerife.

- The flight engineer and first officer seemed to hesitate to challenge the captain. The investigation suggested this was because he was a very respected pilot. However, some who knew them disagreed. The first officer did try to stop the captain once. The flight engineer asked if the runway was clear. But they were not firm enough to stop the takeoff.

- The flight engineer was the only one who reacted to the control tower's message, "report the runway clear." This might be because he had finished his checks. The other pilots were busy as visibility got worse.

- The KLM crew might not have known the message "Papa Alpha One Seven Three Six, report the runway clear" was for the Pan Am. This was the first time the Pan Am was called by that name. Before, it was called "Clipper One Seven Three Six."

The extra fuel the KLM plane took on also played a role:

- It delayed takeoff by 35 minutes, giving the fog more time to settle.

- It added over 45 tonnes of weight. This made it harder for the plane to take off and clear the Pan Am.

- The extra fuel made the fire much worse. This led to everyone on board dying.

What Changed After

Because of this accident, big changes were made to airline rules around the world.

- Aviation authorities now require standard phrases for radio talks. English is now the main working language for pilots and controllers.

- Pilots must not just say "OK" or "Roger" to confirm instructions. They must repeat the important parts of the instruction. This shows they truly understand.

- The word "takeoff" is now only used when permission to take off is given or canceled. Before that, pilots and controllers use "departure."

- If a plane is already on the runway, any clearance must start with "hold position."

Cockpit rules also changed.

- The idea that the captain is always right was changed. Now, team decision-making is encouraged.

- Less experienced crew members are told to speak up if they think something is wrong. Captains are told to listen to their crew.

- This led to crew resource management (CRM). CRM teaches that all pilots, no matter their experience, can question each other. This was a problem in the crash. The flight engineer asked if the runway was clear. But the captain, who had flown for over 11,000 hours, said it was. The flight engineer then decided not to argue.

- CRM training has been required for all airline pilots since 2006.

In 1978, a second airport opened in Tenerife. This was the new Tenerife South Airport (TFS). It now handles most international tourist flights. Los Rodeos was renamed Tenerife North Airport (TFN). It was used for flights within Spain until 2002. Then, a new terminal opened, and Tenerife North started handling international flights again.

The Spanish government also put in a ground radar system at Tenerife North Airport after the accident.

Memorials

There is a memorial and resting place for the KLM victims in Amsterdam, Netherlands. It is at Westgaarde cemetery. There is also a memorial at Westminster Memorial Park in Westminster, California, USA.

In 1977, a cross was dedicated in Rancho Bernardo. It honored 19 local people who died in the disaster.

In 2007, on the 30th anniversary, Dutch and American families of victims met. Aid workers from Tenerife also joined them. They held a special service at the Auditorio de Tenerife. The International Tenerife Memorial March 27, 1977 was opened that day. It was designed by Dutch artist Rudi van de Wint.

Documentaries

The Tenerife disaster has been shown in many TV shows and documentaries. Some of these include:

- Survival in the Sky, "Blaming the Pilot" (1996)

- Seconds From Disaster, "Collision on the Runway" (2004)

- PBS's NOVA, "The Deadliest Plane Crash" (2006)

- Destroyed in Seconds

- Mayday (also known as Air Crash Investigation), "Disaster at Tenerife" (2016) and "Crash of the Century" (2005).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Desastre aéreo de Tenerife para niños

In Spanish: Desastre aéreo de Tenerife para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |