The Four Hundred (Gilded Age) facts for kids

The Four Hundred was a special list of important people in New York City during a time called the Gilded Age. This group was led for many years by Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, who everyone knew as "Mrs. Astor." After she passed away, three other women took her place in society: Mamie Fish, Theresa Fair Oelrichs, and Alva Belmont. They were known as the "triumvirate" of American society.

On February 16, 1892, The New York Times newspaper printed the "official" list of people in the Four Hundred. This list was given by Ward McAllister, a close friend of Mrs. Astor and a social expert. People had been asking for years to know exactly who was on this famous list.

Contents

The History of the Four Hundred

How the "Four Hundred" List Started

After the American Civil War, New York City grew very quickly. Many new people, including immigrants and wealthy newcomers from the Midwestern United States, started to challenge the old, established families of New York. Mrs. Astor, with help from Ward McAllister, tried to set rules for good manners and decide who among these new wealthy people was "acceptable" in high society. They wanted to protect the traditions of the old, rich families.

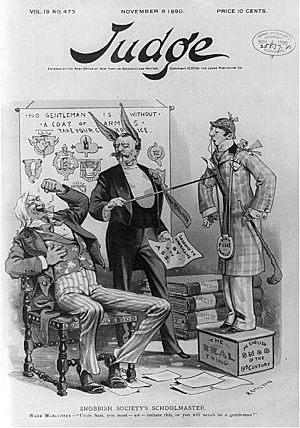

It's said that Ward McAllister came up with the name "the Four Hundred." He claimed there were "only 400 people in fashionable New York Society." According to him, these were the only people in New York who truly mattered. They were the ones who felt comfortable at fancy parties and balls. In 1888, McAllister told the New-York Tribune newspaper that if you went outside this number, you would find people who were either not comfortable at a ball or made others uncomfortable.

Many people believe the number "four hundred" came from the size of Mrs. Astor's ballroom. Her large home at 350 Fifth Avenue and East 34th Street (where the Empire State Building stands today) could supposedly fit only 400 guests. However, the exact reason for the number isn't fully known. Other places in New York at the time, like Delmonico's restaurant and local cotillion dances, also had a maximum capacity of around 400 people. This might have helped make the number "four hundred" popular.

The Official List of February 1892

Other newspapers, like the New York World, started publishing their own lists of New York society members. The World even claimed there were only 150 truly important people. In response, McAllister spoke with The New York Times. He disagreed with the World article and gave the Times what he called the "official list." This list was published on February 16, 1892.

McAllister explained that the "Four Hundred" had not shrunk to 150 names. He said the other lists were "incomplete" and unfair to many wealthy people who should be included. He mentioned important names like Chauncey Depew, Gen. Alexander S. Webb, and the Vanderbilt family.

He also explained that during the social season, there were three big dinner dances. Invitations were sent to different people each time. So, while only 150 people were at each dinner dance, a total of 400 different invitations were sent out over the season. He promised the Times a "correct list" that would be "authorized, reliable, and the only correct list."

This "official" list was supposed to include the very best of New York society. It mostly featured bankers, lawyers, stockbrokers, real estate owners, and railroad owners. There was also one editor, one publisher, one artist, and two architects. The list included both "Nobs" and "Swells." "Nobs" were people from old money families, like the Astors and the Livingstons. "Swells" were the nouveau riche, meaning newly rich people. Mrs. Astor, even if she didn't always like it, felt these "Swells" could join polite society. The Vanderbilt family is a good example of these "Swells."

Reactions to the List

After McAllister's list of the Four Hundred was published in The New York Times, many people were not happy. There was a lot of criticism against the idea of having a fixed list of "acceptable society" members. People also criticized McAllister himself. Newspapers started calling him "Mr. Make-a-Lister." He had also published his memories in a book called Society as I Have Found It in 1890. These actions made the "old guard" (the very traditional wealthy families) dislike him even more. They valued their privacy, especially since society leaders back then were like today's movie stars.

William d'Alton Mann, who owned a gossip magazine called Town Topics, felt it was his job to share the secrets of society. He often criticized the Four Hundred.

Years later, a famous author named O. Henry wrote a collection of short stories called The Four Million. This was his way of reacting to the "Four Hundred" list. He believed that every person in New York City was important and deserved to be noticed, not just a select few.

In 2009, the Museum of the City of New York created its own list called "The New York City 400." This list included 400 "movers and shakers" who had made a big difference in the 400 years of New York City history since Henry Hudson arrived in 1609. Interestingly, McAllister was the only person from the original Four Hundred list who also made it onto the museum's new list.

Notable Members of "The Four Hundred"

McAllister's list had fewer than 400 people. It also had many mistakes. Names were often spelled wrong or were incomplete. Many spouses were left out or included even if they had already passed away. At that time, social rules said that only the oldest unmarried daughter in a family used the title "Miss" without her first name. But McAllister often ignored this rule.

Here are some of the people who were named on the list:

- Mrs. Astor

- Ward McAllister

- Chauncey Depew

- Mamie Fish

- Alva Belmont

- Cornelius Vanderbilt II and Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt

- William Kissam Vanderbilt

- Ogden Mills and Ruth Livingston Mills

- Bradley Martin and Cornelia Sherman Martin

- William Collins Whitney

- George Washington Vanderbilt II

Images for kids

-

Alva Smith Vanderbilt at her 1883 Ball, dressed as a "Venetian Renaissance Lady." She was one of Mrs. Astor's successors.

-

Mamie Fish, wife of Stuyvesant Fish, and one of Mrs. Astor's successors.

-

Portrait of Elizabeth Astor Winthrop Chanler, painted by John Singer Sargent in 1893.

-

Chauncey Depew, a U.S. Senator and president of the Vanderbilt's New York Central Railroad, around 1908.

-

Julia Dent Grant, who married Prince Mikhail Cantacuzène in 1899. She was the granddaughter of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant. Photo taken in 1904.

-

William Kissam Vanderbilt, first husband of Alva Smith Vanderbilt.

-

Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, at Alva's 1883 Ball, dressed as 'Electric Light'. Her gown was by Charles Frederick Worth.

-

Portrait of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, husband of Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt, by John Singer Sargent, 1890.

-

A small portrait of Cornelia Sherman Martin, wife of Bradley Martin. She hosted the famous Bradley-Martin Ball in 1897.

-

Portrait of Emily Thorn Vanderbilt, wife of businessman William Douglas Sloane, by Benjamin Curtis Porter, 1888.

-

Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Anson Phelps Stokes, a merchant and banker, by Cecilia Beaux around 1898.

-

Portrait of Florence Adele Vanderbilt Twombly, wife of Hamilton McKown Twombly, by John Singer Sargent, 1890.

-

Portrait of George Washington Vanderbilt II, who built the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, by John Singer Sargent, 1890.

-

William Collins Whitney, former U.S. Secretary of the Navy during the Cleveland administration, photographed around 1892.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |