The Troubles (1920–1922) facts for kids

The Troubles of the 1920s was a time of fighting in what is now Northern Ireland. It lasted from June 1920 to June 1922. This happened during and after the Irish War of Independence and the partition of Ireland.

It was mainly a conflict between two groups. One group was Protestant unionists. They wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom. The other group was Catholic Irish nationalists. They wanted Ireland to be independent.

During this time, over 500 people died in Belfast. About 23,000 people lost their homes in the city. Around 50,000 people left the north of Ireland because they felt unsafe. Most of the people who died were Catholics.

During the Irish War of Independence, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) attacked British forces. In return, loyalists often attacked Catholic communities. In July 1920, loyalists forced 8,000 workers, mostly Catholics, out of the Belfast shipyards. This started violence between the groups in the city. That summer, fighting also broke out in Derry, killing twenty people. Many Catholic homes were burned, and Catholics were forced out of their homes in Dromore, Lisburn and Banbridge.

The fighting continued for two years, mostly in Belfast. There was "savage and unprecedented" violence between Protestants and Catholics. Almost 1,000 homes and businesses were destroyed. Thousands of people had to leave mixed neighborhoods. The British Army was sent in. The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), also called the "Specials," was formed to help the police. The USC was almost entirely Protestant. Members of both police groups attacked Catholics in return. The Irish Republic supported a 'Belfast Boycott' of unionist-owned businesses. The IRA made sure the boycott was followed. They stopped trains and lorries and destroyed goods.

A truce began on July 11, 1921. This stopped most of the fighting in Ireland. Before this, Belfast's Bloody Sunday happened. Twenty people were killed on that day. In early 1922, violence in Belfast started again. This included the McMahon killings and the Arnon Street killings. In May 1922, the IRA started their Northern Offensive. There were fights near the new Irish border, at Clones and the Pettigo/Belleek area. Also in May 1922, the new Northern Ireland government used the Special Powers Act. This allowed them to hold suspected IRA members without trial. It also put a nighttime curfew across the six Counties. The start of the Irish Civil War in the south on June 28, 1922, made the IRA stop its fight against the Northern government. Violence in Northern Ireland then dropped sharply.

Why the Troubles Started

In the early 1900s, all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. Most people in Ireland were Catholics and Irish nationalists. They wanted Ireland to govern itself ("home rule") or be fully independent.

However, in the north-east of Ireland, Protestants and Unionists were the majority. This was largely because of British settlement in the 1600s. Home Rule for Ireland had been a big issue for many years. In 1886, the first Home Rule Bill was introduced. Ulster Unionists fought against this Bill with violence. Many riots happened in Belfast during the 19th century.

Home rule for all of Ireland was planned with the Government of Ireland Act 1914. During the Home Rule Crisis of 1912–14, Unionists threatened to fight any Irish government. They formed a group called the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and got weapons. British Army officers even said they would resign if told to enforce the Home Rule Act. Ulster unionists wanted all or part of Ulster to be left out of Home Rule.

The Act divided Ireland along county lines. It created two self-governing parts of the UK: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Six of Ulster's nine counties became Northern Ireland. Unionists believed they could control this area. Many Irish nationalists did not want Ireland to be divided.

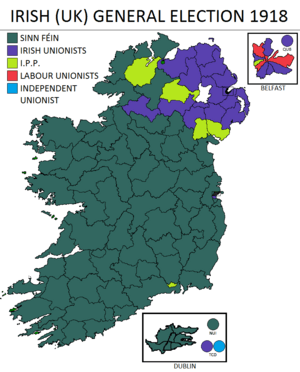

By the end of First World War, most Irish nationalists wanted full independence. In the 1918 election, the Irish republican party Sinn Féin won most Irish seats. Sinn Féin's elected members did not go to the British parliament. Instead, they formed their own Irish parliament (Dáil Éireann). They said an independent Irish Republic was formed for the whole island. Unionists, however, won most seats in Ulster. They stayed loyal to the United Kingdom.

Many Irish republicans blamed the British for the divisions in Ireland. They thought Ulster Unionists would change their minds if British rule ended. British authorities banned the Dáil in September 1919. Then, a guerrilla war started as the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) attacked British forces. This was called the Irish War of Independence.

Another reason for the violence was a bad economy after World War I. Many people lost their jobs. Some Protestant soldiers returning from war felt angry that Catholics had jobs they wanted. At the same time, Unionist leaders gave strong speeches. Loyalists and nationalists also gathered weapons.

In June 1920, the Ulster Unionist Council restarted the UVF. The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, also formed the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division. These groups were made of returning soldiers to help the police. But they became known for their harsh actions against nationalists.

Belfast Shipyard Worker Expulsions (1920)

Large numbers of workers were forced out of the shipyards in July 1920. Similar events happened in 1898 and 1912. These expulsions mainly targeted Catholic shipyard workers and some Protestant trade unionists. In 1898, about 700 Catholic workers were driven from shipyards and other businesses. In 1912, 2,400 Catholics and 600 Protestant trade unionists were forced from their jobs.

Belfast Violence and Expulsions

On The Twelfth (July 12) 1920, a Protestant celebration, Unionist leader Edward Carson gave a speech. He told thousands of Orangemen that he was "sick of words without actions." He warned the British government that if it did not protect Unionists, they would act themselves. He also linked Irish republicanism to socialism and the Catholic Church. Many Catholics believed Carson's words helped start the violence against them. They called it the Belfast Pogrom.

In Belfast, Catholics were a quarter of the city's population. But they made up two-thirds of those killed. They suffered 80% of the property damage and were 80% of the refugees. Some historians say "pogrom" is not the right word. They say the police violence was not planned.

On July 21, 1920, shipyard workers returned after holidays. A meeting of "all Unionist and Protestant workers" was called. Speeches demanded that all "non-loyal" workers be removed. Hours of threats and violence followed. Loyalists forced 8,000 co-workers from Harland and Wolff and other workplaces. All removed workers were either Catholics or Protestant labour activists. Some were beaten or thrown into the water. Three days of rioting followed. Eleven Catholics and eight Protestants were killed. Hundreds were hurt.

The removal of thousands of Catholic workers led to attacks on Protestant workers. This started a cycle of violence that lasted over two years. On November 22, 1921, bombs were thrown into a tram carrying workers. Three workers died and 16 were hurt.

In the Falls-Shankill area, seven Catholics and two Protestants were killed. Most were killed by soldiers trying to stop rioters. A Loyalist mob tried to burn a Catholic convent. Soldiers guarding it fired, wounding 15 Protestants, three of them fatally.

Expulsions continued at other workplaces. Hundreds of female textile workers were also forced out. Catholics and Socialists were driven from large companies. About 11,000 Catholic workers were expelled from their jobs. This was a tenth of Belfast's Catholic population. Sir James Craig, the Unionist leader, supported the expulsions. He said, "Do I approve of the actions you boys have taken in the past? I say yes."

Unemployed Catholic shipyard workers continued to attack Protestants going home. In late November 1921, trams carrying shipyard workers were attacked. Eight Protestant workers were killed. Loyalist revenge attacks killed fifteen Nationalists on November 22, 1921. St. Matthew's church in the Catholic area of Ballymacarrett was attacked. In March 1922, St. Mathews Primary School was also bombed.

Peace Walls

In the 1920s, temporary Peace lines (walls) were built near the Harland & Wolff shipyards. These became permanent in 1969. Today, the Ballymacarrett/Short Strand areas are still separated. Violence still happens there.

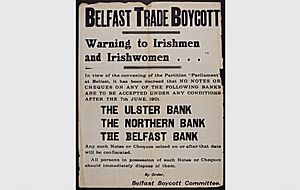

Belfast Boycott

After Catholic workers were expelled and violence spread, Sinn Féin members in the north called for a boycott of Unionist-owned businesses and banks in Belfast. The Dáil (Irish parliament) approved the boycott in August 1920. They stopped goods from Belfast and pulled money from Belfast banks. In January 1921, the Dáil gave money to support the boycott.

The IRA enforced the boycott. They stopped trains and lorries and destroyed goods from Belfast. Women from Cumann na mBan also helped stop trains and destroy goods. The boycott had little effect on the north's main industries: farming, shipbuilding, and linen. These were mostly shipped outside Ireland.

In March 1922, Craig and Collins made an agreement. Craig would try to get Catholic workers their jobs back. Collins agreed to stop IRA actions and end the boycott. The Belfast Boycott ended after the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 and the start of the Irish Civil War in June 1922.

Violence in Banbridge and Dromore

On July 17, 1920, the IRA killed British Colonel Gerald Smyth in Cork. He had told police to shoot civilians who did not obey orders. Smyth was from a rich Protestant family in Banbridge, County Down. His funeral was there on July 21, the same day as the Belfast shipyard expulsions.

After Smyth's funeral, about 3,000 Loyalists went into the streets. Many Catholic homes and businesses were attacked, burned, and robbed. Police were present but did not stop it. A large mob attacked a republican family's home. The father shot and killed a Protestant man. Hundreds of Catholic factory workers were also forced from their jobs. Many Catholic families fled Banbridge. The British Army was sent in to restore calm.

On July 23, 1920, violence also happened in Dromore, County Down. About 500 people attacked Catholic homes and businesses. One Orange Order member was shot dead by police trying to break up the mob. After these two days, almost all Catholics in Banbridge and Dromore were forced to leave their homes. Violence continued in Banbridge, and about 1,000 more Catholics lost their jobs.

Lisburn Attacks

Attacks also happened in Lisburn County Antrim, near Belfast. This was after Colonel Smyth's murder. On July 24, 1920, rioters attacked Catholic businesses, homes, and a Catholic convent.

On August 22, 1920, the IRA killed police Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn. A court had said Swanzy was responsible for the murder of Tomás Mac Curtain, Cork's Irish republican mayor.

For the next three days, Loyalist crowds robbed and burned almost every Catholic business in Lisburn. They also attacked Catholic homes. Some said it was like ethnic cleansing. There is proof the UVF helped organize the burnings. Rioters attacked firefighters trying to save Catholic property. A Catholic pub owner later died from gunshot wounds. A charred body was found in a factory.

Lisburn looked like "a bombarded town in France" during World War I. A third of the town's Catholics (about 1,000 people) fled Lisburn. The attacks in Lisburn, Dromore, and Banbridge caused a long-term drop in the Catholic populations there. Damage in Lisburn was estimated at 810,000 pounds (in 1920 money).

Ulster Special Constabulary (USC)

In September 1920, Unionist leader James Craig asked the British government to recruit a special police force from the UVF. He warned that Loyalists might start organized attacks if the government did not act. The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) was formed in October 1920. It was like an official UVF. Irish nationalists saw this mostly Protestant force as arming one group against the Catholic minority.

After the truce between the IRA and the British (July 11, 1921), the USC was temporarily stopped. The USC had 32,000 men. They were divided into A, B, and C Specials. The USC was used throughout the 20th century until it was disbanded in May 1970.

Violence in 1921

After a quiet period, fighting in the north grew stronger in spring 1921. On April 1, the IRA attacked police and army posts in Derry. Two police officers were killed. On April 10, the IRA attacked Special Constables in Creggan, County Armagh. One was killed. In return, the USC attacked nationalists and burned their homes in Killylea. On June 10, the IRA shot three police officers in Belfast. One died. He was targeted because the IRA thought he was involved in killing Catholics. These attacks caused Loyalists to start violence. Belfast had three days of rioting and shootings. At least 14 people were killed, including three Catholics taken from their homes and killed by police. About 150 Catholic families were forced from their homes.

Ireland is Divided

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 divided Ireland under British law on May 3, 1921. Elections for the Northern and Southern parliaments were held on May 24. Unionists won most seats in Northern Ireland. Republicans saw it as an election for the Dáil. The Parliament of Northern Ireland met for the first time on June 7. It formed a government led by James Craig. Irish nationalist and republican members did not attend. The next day, the IRA attacked a USC patrol near Newry. In return, Special Constables went to a Catholic home and shot two civilian men dead. The IRA then fired on the USC men, killing one.

Opening of the Northern Parliament

King George V spoke at the opening of the Northern Parliament on June 22, 1921. He asked "all Irishmen to pause, to stretch out the hand of forbearance and conciliation." The next day, an IRA bomb derailed a train carrying the king's military escort. Five soldiers and a train guard were killed. On July 6, Special Constables raided homes and killed four Catholic civilian men.

Belfast's Bloody Sunday

On July 9, 1921, a ceasefire was agreed between the Irish Republic and the British government. It was to start at noon on July 11. Many Loyalists felt betrayed by this truce. While violence stopped in the south, the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 brought another wave of intense violence to Belfast. This time saw the most deaths since the Shipyard Expulsions.

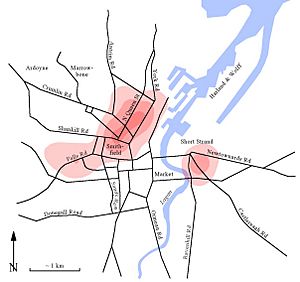

Hours before the ceasefire, police raided Republicans in west Belfast. The IRA attacked them, killing one officer. This started a day of violence called Belfast's Bloody Sunday. Protestant loyalists attacked Catholic neighborhoods in west Belfast. They burned over 150 Catholic homes and businesses. This led to fights and gun battles between police and Catholic nationalists. The USC was accused of driving through Catholic areas and shooting randomly. Twenty people were killed or fatally wounded before the truce began at noon on July 11, 1921. Almost 200 houses were badly damaged or destroyed, mostly Catholic homes.

A strict curfew was put in place in Belfast. After the ceasefire, an IRA leader, Eoin O'Duffy, was sent to Belfast. He worked with authorities to keep the truce. He organized IRA patrols in Catholic areas and said IRA attacks would stop. Both Protestants and Catholics saw the truce as a win for Republicans. Loyalists were upset to see police and soldiers meeting with IRA officers.

The Troubles in Ulster

During this time, violence happened in all nine counties of Ulster. Outside major cities, many attacks happened in smaller communities. These were mostly attacks on police stations, ambushes, and raids for weapons. Some large attacks did occur. For example, on May 9, 1920, about 200 IRA volunteers attacked a police station in Newtownhamilton, County Armagh.

Attacks and revenge were common. On October 25, 1920, after an IRA raid for weapons, a police officer was badly hurt. Hours later, UVF members shot into a group of civilians, killing one. On February 22, 1921, in Mountcharles, County Donegal, the IRA attacked police and soldiers. One police officer was killed. Later that day, police and Black and Tans destroyed shops and homes in Donegal town and Mountcharles. One woman was shot and killed.

In March 1921, the IRA attacked Protestant homes in Rosslea, County Fermanagh, burning some down. The next month, the IRA attacked the homes of Special Constables in the Rosslea area. They killed three and wounded others.

In Ulster in spring 1921, British and Unionist forces had more men than the IRA. For example, in County Tyrone, there were 3,515 A and 11,000 B Specials. The IRA had about 14 companies, each with 50 men, but only a few had weapons. So, about 100 poorly armed IRA volunteers faced almost 3,000 heavily armed police. The British Army also had 650 men in Strabane. Some areas of Ulster saw little violence.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The talks after the ceasefire led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It was signed on December 6, 1921, by British and Irish representatives. Under the Treaty, 'Southern Ireland' would leave the UK and become the Irish Free State. Northern Ireland's parliament could choose to join or not join the Free State. A Boundary Commission would then decide the final border.

The Dáil approved the Treaty by a close vote (64 to 57) on January 7, 1922. But it caused a big split in the Irish nationalist movement. This led to the Irish Civil War. Those against the Treaty said it made the division of Ireland permanent. Those for the Treaty believed the Boundary Commission would give large parts of Northern Ireland to the Free State. The pro-Treaty side formed a government led by Michael Collins.

Early 1922 Events

The first half of 1922 saw clashes between the IRA and USC along the new border. There was also an IRA attack inside Northern Ireland. Violence and killings continued in Belfast. Tensions grew between the two new governments.

On January 14, Northern Ireland police arrested members of the Monaghan Gaelic football team. Some were IRA volunteers planning to free prisoners. In response, on February 7–8, IRA units went into Northern Ireland. They captured almost fifty Special Constables and Loyalists in counties Fermanagh and Tyrone. They were held as hostages for the Monaghan prisoners. Northern Ireland authorities then blocked many cross-border roads.

On February 11, the IRA stopped Special Constables at Clones railway station. The USC unit was traveling by train from Belfast to Enniskillen. The Irish government did not know British forces would cross its land. The IRA asked the Special Constables to surrender. But one shot and killed an IRA sergeant. This started a gunfight. Four Special Constables were killed, and five were captured. This incident almost caused a major fight between North and South. The British government temporarily stopped withdrawing troops from the South. A Border Commission was set up to help with future border problems, but it did little.

These events caused Loyalists to attack Catholics in Belfast. This led to more violence between the groups. In the three days after the Clones incident, over 30 people were killed in Belfast. On February 14, Loyalists threw a bomb at Catholic children playing. Two children died, and 22 were hurt. On March 18, 1922, Northern Ireland police raided IRA headquarters in Belfast. They took weapons and lists of IRA volunteers. The Irish government said this broke the truce. Over the next week, the IRA attacked several police stations in the North. On March 28, fifty IRA volunteers seized a police station in Belcoo, County Fermanagh. Fifteen police officers were captured and held until July 18.

McMahon Family and Arnon Street Killings

One of the worst attacks in Belfast was the McMahon killings (March 24, 1922). Five Catholic family members and an employee were shot dead in their home. The gunmen were said to be Special Constables. It was believed to be revenge for the IRA killing two policemen hours earlier. A week later, six more Catholics were killed by Special Constables in the Arnon Street killings (April 1, 1922). This was also thought to be revenge for an IRA killing of a policeman.

Battle of Pettigo and Belleek

During the Northern Offensive, there were fights between the IRA and British forces near Belleek, County Fermanagh and Pettigo. This area was part of Northern Ireland but mostly cut off by Lough Erne and the border. The IRA had soldiers in these villages and the nearby Northern territory. On May 27, 1922, a USC group was sent into the area. The IRA attacked them, forcing them to retreat. The IRA also attacked a group of USC reinforcements, killing the driver.

James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, asked Winston Churchill to send British troops to drive out the IRA. Over the next week, many Specials and British troops tried to capture Pettigo from about 100 IRA volunteers. British forces bombed the village and then stormed it, capturing Pettigo on June 4. Three IRA volunteers were killed by British shelling. Most other IRA volunteers retreated. Belleek was captured by British troops on June 8 after a short battle. They bombed the old Belleek Fort, forcing the IRA to retreat. Newspaper reports said seven IRA members were killed, and the total death toll was as high as 30. British troops stayed in Pettigo until January 1923 and Belleek Fort until August 1924.

This fighting increased tensions between the Irish and British governments. It was the first clash between the IRA and British troops since the truce. It was also the last major conflict between the IRA and British forces during this period.

Facts and Figures

Between 1920 and 1922, 557 people were killed in Northern Ireland. This included 303 Catholics, 172 Protestants, and 82 police and British Army members. Some IRA volunteers also died. Belfast had the most deaths, with 455 people killed. This included 267 Catholics, 151 Protestants, and 37 security force members. Belfast had a higher death rate than any other part of Ireland during this time.

Almost 1,000 homes and businesses in Belfast were destroyed. About 80% were Catholic, and 20% were Protestant. More than 10,000 people became refugees. Most were Catholics who fled to other parts of Ireland. About 8,000 Catholics and 2,000 Protestants had to move within Belfast alone. An estimated 8,000–10,000 workers, mostly Catholics, lost their jobs.

Catholic relief groups estimated that 8,700 to 11,000 Catholics had lost their jobs. Up to 23,000 Catholics had been forced from their homes. About 500 Catholic-owned businesses were destroyed between July 1920 and July 1922.

Outside Belfast, at least 104 people were killed. This included 61 civilians (45 Catholics and 15 Protestants) and 45 police/soldiers.

Both groups suffered violence. But Catholics were affected much more. Catholics were less than a quarter of Belfast's population. But they were almost two-thirds of the victims.

What is a "Pogrom"?

Many Irish Catholics in Belfast felt the Loyalist violence was like a "pogrom" or "ethnic cleansing". They felt it was an organized effort to drive them out. The American Commission on Conditions in Ireland said in 1921 that the riots were like "Russian pogroms against the Jews." Some believed the Catholic population had been "beaten into submission."

Historians have debated if "pogrom" is the right word. Some argue it is not, because both groups used violence. In the Belfast shipyard expulsions, the word "pogrom" does not perfectly fit dictionary definitions. These usually refer to attacks on Jews in Eastern Europe. Both groups used intimidation and revenge attacks. About a third of those killed and over 20% of refugees were Protestant.

Later Troubles

There were no major outbreaks of violence until May 1935. Then, Catholic homes in Belfast were set on fire. In June 1935, a crowd attacked a small Catholic area. The IRA helped defend this area. Attacks continued through the summer on Catholic homes. By the end of 1935, thirteen people had been killed. Hundreds were wounded. Many Catholics were again forced from shipyard jobs. A Catholic group said that mobs had forced 431 families from their homes. Dozens of houses were burned. Over 2,500 people were driven from their homes, with 85% being Catholic. Many Catholics called these events "pogroms" against them.

In The Troubles that began in 1969, some Belfast Catholics were attacked again. Their homes had been attacked when they were children. It seemed like a repeat of the 1920-1922 troubles. The Belfast shipyards were known as Protestant-only workplaces. In 1970, 500 Catholic workers were again forced from their jobs.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |