Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

General William T. Sherman (third from left) and Commissioners in council with chiefs and headmen, Fort Laramie, 1868

|

|

| Signed | April 29 – November 6, 1868 |

|---|---|

| Location | Fort Laramie, Wyoming |

| Negotiators | Indian Peace Commission |

| Signatories |

|

| Ratifiers | US Senate |

| Language | English |

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (also called the Sioux Treaty of 1868) was an important agreement. It was signed between the United States government and several groups of Lakota people (like the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé), the Yanktonai Dakota, and the Arapaho Nation. This treaty came after an earlier one from 1851 didn't work out.

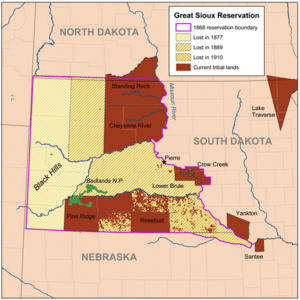

The treaty had 17 main parts, called articles. It created the Great Sioux Reservation, which included the Black Hills. It also set aside other lands as "unceded Indian territory" in areas that are now South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, and possibly Montana.

The agreement said that the US government would deal with crimes. This meant punishing white settlers who harmed tribes, and also tribe members who committed crimes. The government wanted these tribe members to face charges in government courts, not tribal ones.

The treaty also stated that the US government would leave forts along the Bozeman Trail. It included ideas to help the tribes learn farming and live "closer to the white man's way of life." The treaty helped end Red Cloud's War.

However, there was a problem with the Ponca tribe. They were not part of this treaty. The American negotiators accidentally sold the Ponca's land to the Lakota. The US government never helped the Ponca get their land back. The Lakota then claimed the Ponca land. This led to the US President Ulysses S. Grant ordering the Ponca to be moved by force in 1877. This forced move was very sad and is known as the Ponca Trail of Tears.

The Indian Peace Commission, a group chosen by the government, helped create this treaty. It was signed between April and November 1868 at Fort Laramie in Wyoming. One of the last people to sign was Red Cloud himself.

Soon after, problems started because neither side fully followed the treaty. Fighting broke out again in 1876. The US government then took back land that was protected by the treaty in 1877.

This treaty was a key part of a 1980 Supreme Court case called United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians. The court decided that the US government had illegally taken tribal lands. They said the tribe should get money as payment, plus interest. By 2018, this amount was over $1 billion. But the Sioux people have refused the money. They want their land back instead.

Who Signed the Treaty?

Many important people signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie. Here are some of them, listed in the order they signed. Two people are listed out of order: Henderson, who was a commissioner but didn't sign, and Red Cloud, who signed later but is listed with other Oglala leaders.

Commissioners (US Government Representatives)

These people represented the United States government during the treaty talks:

- Nathaniel Green Taylor, who was in charge of Indian Affairs.

- William Tecumseh Sherman, a lieutenant general in the US Army.

- William S. Harney, a major general in the US Army.

- John B. Sanborn, a former general and member of an earlier peace group.

- Samuel F. Tappan, a journalist and activist who looked into the Sand Creek massacre.

- Christopher C. Augur, a Major General who commanded the Department of the Platte.

- Alfred Terry, a major general in the US Army.

- John B. Henderson, a US Senator and leader of the Senate's Indian Affairs committee.

Chiefs and Headmen (Native American Leaders)

These leaders represented their tribes and signed the treaty:

Brulé Lakota

Oglala Lakota

- Young Man Afraid Of His Horses

- Sitting Bull (Some sources question if he signed, but his name is on the treaty.)

- American Horse

- Blue Horse

- Red Cloud (He was one of the last to sign. He waited until the army left the forts along the Bozeman Trail, as they had promised.)

Arapaho Nation

- Black Bear

- Black Coal

- Sorrel Horse

Miniconjou Lakota

- Lone Horn

- Spotted Elk

- Big Eagle

Yanktonai Dakota

What Happened After the Treaty?

The treaty said that three-fourths (75%) of the men from the tribes needed to agree to it. However, many did not sign or accept the results. Some later said the treaty was written in confusing language. They felt it wasn't explained clearly to them. Others didn't fully understand the agreement until 1870. That's when Red Cloud returned from a trip to Washington D.C.

This treaty was different from the 1851 agreement. It showed that the government was taking a stronger stance. They wanted to change tribal customs and encourage the Sioux to live more like white Americans.

Problems with the treaty started almost right away. A group of Miniconjou were told they couldn't trade at Fort Laramie anymore. This was because they were south of their new territory. But the treaty didn't say tribes couldn't travel outside their land. It only said they couldn't live there permanently. The treaty only stopped white settlers from traveling onto the reservation.

Even though this was a treaty between the US and the Sioux, it greatly affected the Crow tribe. The Crow tribe owned some of the lands that were set aside in the new treaty. By making peace with the Sioux, the government seemed to betray the Crows. The Crows had helped the army protect the Bozeman Trail.

When the Sioux stopped the US army in 1868, they quickly started expanding again. They moved into nearby Indian territories. The Sioux and their allies often attacked the Crows and the Shoshones. The Crows reported seeing Sioux in the Bighorn area by 1871. This eastern part of the Crow reservation was taken over by the Sioux looking for buffalo.

In 1873, Sioux warriors faced a Crow camp at Pryor Creek all day. The Crow chief, Blackfoot, asked the US to take strong action against these intruders. In 1876, the Crows and Eastern Shoshones fought alongside the US Army. They helped scout for General Custer against the Sioux, who were now in the old Crow country.

Both the tribes and the government sometimes ignored parts of the treaty. They would only follow it if it was good for them at the time. Between 1869 and 1876, there were at least seven fights near Fort Laramie. Army reports also mentioned Sioux attacks in Montana and North Dakota.

The government eventually broke the treaty after gold was discovered in the Black Hills. This led to the Black Hills Gold Rush. George Armstrong Custer led an expedition into the area in 1874. The government failed to stop white settlers from moving onto tribal lands. These rising tensions led to more fighting in the Great Sioux War of 1876.

The 1868 treaty was changed three times by the US Congress between 1876 and 1889. Each time, more land that was originally given to the tribes was taken away. This included the Black Hills, which were taken by force in 1877.

The Supreme Court Case: United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians

On June 30, 1980, the US Supreme Court made a big decision. They ruled that the government had illegally taken land in the Black Hills. This land was promised to the Sioux by the 1868 treaty. The court said the government broke the treaty in 1876. They did this without getting the required signatures from two-thirds of the adult male population.

The court decided that the Sioux should receive $15.5 million for the value of the land in 1877. They also added 103 years of interest at 5 percent, which added another $105 million. However, the Lakota Sioux have refused to accept this money. They continue to demand that their land be returned to them. As of August 24, 2011, the interest on the money had grown to over $1 billion.

Remembering the Treaty

To mark 150 years since the treaty, the South Dakota Legislature passed a resolution. This resolution confirmed that the treaty is still valid. It showed the federal government that the Sioux are "still here." It also expressed a desire for positive relationships with full respect for the tribes' independent status, as confirmed by the treaty.

On March 11, 2018, the Governor of Wyoming, Matt Mead, signed a similar law. This law asked the federal government to keep its promises. It also asked for the original treaty to be shown permanently in the Wyoming Legislature. The original treaty is kept at the National Archives and Records Administration.

See also

In Spanish: Tratado del fuerte Laramie (1868) para niños

In Spanish: Tratado del fuerte Laramie (1868) para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |