Trotula facts for kids

Trotula is a special name for a collection of three old books about women's health. These books were written in the 1100s in a port city in southern Italy called Salerno. The name "Trotula" comes from a real woman, Trota of Salerno, who was a doctor and writer. She was linked to one of these three books.

However, during the Middle Ages, many people thought "Trotula" was a single, famous doctor. These "Trotula" books were very popular all over medieval Europe, from Spain to Ireland. Because of this, "Trotula" became important in history, even if people misunderstood who she was.

Contents

Discovering the Trotula Texts

In the 1100s, the city of Salerno in southern Italy was famous for bringing new medical ideas from the Arabic world into Europe. When we talk about the School of Salerno from that time, we mean a group of teachers and students. They developed ways of teaching and studying medicine. There wasn't a physical school building until later.

The three books often called The Trotula are: Conditions of Women, Treatments for Women, and Women’s Cosmetics. They cover many topics, from how to give birth to beauty tips. They used different sources, from ancient doctors like Galen to local traditions, and gave practical advice. These books were not always organized the same way.

Conditions of Women and Women’s Cosmetics were first passed around without an author's name. Later, in the late 1100s, they were joined with Treatments for Women. For hundreds of years after that, the Trotula collection was popular across Europe. It was most popular in the 1300s. Today, we still have over 130 copies of the Latin texts. There are also more than 60 copies of translations into other languages from the Middle Ages.

Book on the Conditions of Women

The Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum (which means "Book on the Conditions of Women") was new because it used ideas from Arabic medicine. These ideas were just starting to arrive in Europe. This book used a lot of information from a Latin translation of an Arabic medical text.

Arabic medicine was more about ideas and philosophy. It often followed the principles of Galen. Galen believed that women's monthly bleeding (menstruation) was normal and healthy. He thought women were colder than men and needed to get rid of extra substances through menstruation. The author of this book also saw menstruation as important for women's health and having babies. They wrote: "Menstrual blood is special because it carries in it a living being. It works like a tree. Before bearing fruit, a tree must first bear flowers. Menstrual blood is like the flower: it must emerge before the fruit—the baby—can be born."

The book also talks about other health issues, like problems with monthly bleeding and the womb moving. It also discusses how to care for a newborn baby. All the doctors mentioned in this book were men.

On Treatments for Women

De curis mulierum (meaning "On Treatments for Women") is the only one of the three Trotula books that was actually linked to the doctor Trota of Salerno. This was when it was shared as a separate book. However, some think Trota was more like the expert behind the text, rather than the person who wrote every word.

This book doesn't explain the reasons for women's health problems. Instead, it simply tells readers how to make and use medicines. It covers many different health issues for women, men, and children. It also includes beauty tips. The book focuses a lot on treatments for fertility. It also gives practical advice, like how to "restore" virginity or treat chapped lips from too much kissing. Even though it's mostly about women's health, it includes remedies for men's problems too.

On Women’s Cosmetics

De ornatu mulierum (meaning "On Women's Cosmetics") is a book that teaches how to keep and improve women's beauty. The author likely wanted many people to read it. They even included instructions for a steam bath for women who didn't have access to Italian spas.

The author doesn't claim to have invented all the beauty recipes. They mention one treatment they saw a Sicilian woman create. They also added their own remedy for bad breath. The rest of the book seems to collect remedies from experienced women. The author says they used "the rules of women whom I found to be practical in practicing the art of cosmetics." So, women were their sources, but the book was written for male doctors. These men wanted to learn how to make women beautiful and profit from that knowledge.

The original book mentions Muslim women's beauty practices six times. Christian women in Sicily often copied these. The book also shows a global market of spices and scents, common in the Islamic world. Ingredients like frankincense, cloves, cinnamon, and nutmeg are used often. This book, more than the other two, shows the practical knowledge of southern Italy and the rich culture available when Norman kings in southern Italy adopted Islamic culture in Sicily.

The Trotula in the Middle Ages

The Trotula books are thought to be the "most popular collection of materials on women's medicine" from the late 1100s to the 1400s. We have almost 200 copies of these books (in Latin and other languages). This is only a small part of how many copies were shared across Europe. Different versions of the Trotula were popular everywhere. They were most popular in Latin around the 1300s. Many translations into other languages kept the books popular into the 1400s and even the 1500s in places like Germany and England.

How the Latin Texts Spread

All three Trotula books were shared as separate texts for centuries. Each book exists in different versions, probably because later editors or copyists changed them. However, by the late 1100s, some unknown editors realized these three books about women's medicine and beauty were related. So, they put them together into one collection.

A researcher named Monica Green found eight different versions of the Latin Trotula collection in 1996. These versions have small differences in words. More noticeably, some parts were added, removed, or rearranged. The most complete version was very popular in universities. People who owned the Latin Trotula included learned doctors, monks, surgeons, and even kings of France and England.

Translations into Other Languages

Using everyday languages for medical writing became popular in the 1100s and grew more common later in the Middle Ages. So, the many translations of the Trotula were part of this trend. The first known translation was into Hebrew, made in southern France in the late 1100s. In the 1200s, it was translated into Anglo-Norman and Old French. In the 1300s and 1400s, there were translations into Dutch, Middle English, French (again), German, Irish, and Italian. Recently, a Catalan translation of one of the Trotula texts was found.

These translations show that the Trotula books were reaching new readers. However, these new readers were not always women. Only a few of the translations were clearly for women. Even some of those were read by men. The first known woman to own a copy of the Trotula was Dorothea Susanna von der Pfalz in the late 1500s.

"Trotula's" Fame in the Middle Ages

People in the Middle Ages who read the Trotula books believed what the manuscripts told them. So, "Trotula" was accepted as an expert on women's medicine. For example, a doctor named Petrus Hispanus in the mid-1200s quoted "Lady Trotula" many times. Another doctor, Richard de Fournival, ordered a copy titled "Here begins the book of Trotula, the Salernitan female healer, on treatments for women."

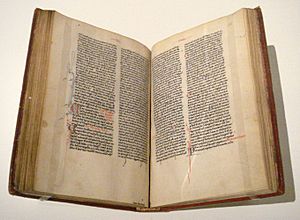

Two copies of the Latin Trotula collection even have drawings of the author. The most famous one is from the early 1300s, now at the Wellcome Library (see image above). Some references from the 1200s only mention "Trotula" as an expert on beauty. People believed "Trotula" was the top expert on women's medicine. This even led to other doctors' works being wrongly given to her. For example, a 1400s book on women's health, written by men, was called the Liber Trotularis in one copy.

Besides being a medical expert, "Trotula" also became a symbol for negative views about women starting in the 1200s. This was partly linked to a general interest in the "secrets of women," meaning how babies are made. When a German doctor named Johannes Hartlieb translated the Trotula in the 1400s, he made "Trotula" a queen. He also paired her book with another text called Secrets of Women, which was not actually by Albertus Magnus.

A text called Placides and Timeus said "Trotula" was a special expert because she "felt in herself, since she was a woman." It also said "all women revealed their inner thoughts more readily to her than to any man." Geoffrey Chaucer shows this idea when he mentions "Trotula" in his "Book of Wicked Wives." This book was owned by the Wife of Bath's husband in The Canterbury Tales.

The Trotula Today

Early Printed Books and Debates

The Trotula books were first printed in 1544. This was quite late compared to other medical texts, which started being printed in the 1470s. The Trotula was printed not because doctors still used it daily. Other books had replaced it in the 1400s. Instead, a publisher in Strasbourg, Johannes Schottus, "discovered" it as an example of practical medicine.

Schottus asked a doctor, Georg Kraut, to edit the Trotula. Schottus then put it in a book called Experimentarius medicinae ("Collection of Tried-and-True Remedies of Medicine"). This book also included the Physica by Hildegard of Bingen, who lived around the same time as Trota of Salerno. Kraut saw that the texts were messy. He didn't realize they were written by three different authors. So, he rearranged the whole work into 61 themed chapters. He also changed the text in places. This made it harder to see the original work of the real woman, Trota.

Kraut and Schottus kept the name "Trotula" for the books. They even gave it a new title that highlighted "Trotula's" female identity. Schottus praised her as "a woman by no means of the common sort, but rather one of great experience and erudition." Kraut made the text seem like an ancient work, not a medieval one. When the book was printed again in 1547, it was in a collection of "Ancient Latin Physicians." From then until the 1700s, people treated the Trotula as if it were an ancient text.

A researcher named Monica Green noted that "Trotula" survived because she seemed ancient, not medieval. But this success also made her "unwomaned." When the Trotula was reprinted eight more times between 1550 and 1572, it was seen as the work of a "very ancient author," not a woman.

In 1566, a man named Hans Caspar Wolf changed the author's name from "Trotula" to Eros. He claimed Eros was a male doctor and a freed slave of a Roman empress. This idea came from a Dutch doctor, Hadrianus Junius, who thought many old texts had wrong authors due to mistakes. Even though this change wasn't meant to be against women, it meant there were no female authors left in the new list of writers on women's health.

Modern Debates and the Real Trota

From 1544 to the 1970s, all discussions about "Trotula" were based on Georg Kraut's printed text. But this text was misleading because it hid that the Trotula was made from three different authors' works. In 1985, a historian named John F. Benton studied past ideas about "Trotula."

Benton's study was important for three main reasons: 1. He showed how much the Renaissance editor had changed the texts. It wasn't one text or one author, but three different texts. 2. He proved that many stories about "Trotula" from the 1800s and early 1900s were false. For example, the name "de Ruggiero" added to her name was made up. Stories about her birth, death, husband, or sons also had no proof. 3. Most importantly, Benton found a text called Practica secundum Trotam ("Practical Medicine According to Trota"). This proved that the real Trota of Salerno existed and was an author.

After Benton passed away, Monica H. Green continued his work. She wanted to publish a new translation of the Trotula for students and scholars. Benton's discoveries meant that the old printed version was no longer useful. So, Green surveyed all the existing Latin manuscripts of the Trotula and created a new edition.

Green disagreed with Benton on one point: she believes not all the Trotula texts were written by men. While she agrees that Conditions of Women and Women's Cosmetics were likely by men, she showed that De curis mulierum (On Treatments for Women) was directly linked to the real Trota of Salerno in its earliest known version. This text also shows a deep understanding of the female body. Given the customs of the time, only a female doctor would likely have had such close access to female patients.

"Trotula's" Fame in Popular Culture

One of the most famous modern uses of "Trotula" was in the artwork The Dinner Party (1979) by Judy Chicago. This art piece, now at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, includes a place setting for "Trotula." The way she is shown there is based on older ideas before Benton's discoveries. It mixes up details that scholars no longer accept.

Chicago's celebration of "Trotula" led to many modern websites mentioning her. Many of these sites still repeat the old, incorrect ideas. A clinic in Vienna, a street in modern Salerno, and even a feature on the planet Venus have been named after "Trotula." All of these mistakenly continue the made-up stories about "her."

Medical writers also keep using old ideas about "Trotula" when talking about women in medicine or the history of certain health problems. However, Judy Chicago's work did highlight how important it is to remember historical women like "Trotula" and Hildegard of Bingen. It took almost 20 years for Benton and Green to find the real Trota within the complex Trotula texts. It is taking even longer for popular ideas about Trota and "Trotula" to catch up with this new knowledge. This raises the question of whether Women's History should also explain how historical facts are found and put together.

See also

- Sator Square, mentioned in the Trotula manuscripts as a remedy

Images for kids

Medieval Manuscripts of the Trotula Texts

Since Monica Green's edition of the Trotula collection came out in 2001, many libraries have put high-quality digital images of their old manuscripts online. Here is a list of Trotula manuscripts you can see online. The list includes the library's code for the manuscript and its index number from Green's lists.

Latin Manuscripts

- Lat16: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.14.30 (903), ff. 187r-204v (new foliation, 74r-91v) (late 1200s, France): early collection (incomplete), [1]

- Lat24: Firenze [Florence], Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 73, cod. 37, ff. 2r-41r (mid-1200s, Italy): middle collection, [2]

- Lat48: London, Wellcome Library, MS 517, Miscellanea Alchemica XII (formerly Phillipps 2946), ff. 129v–134r (late 1400s, probably Flanders): early collection (parts), [3]

- Lat49: London, Wellcome Library, MS 544, Miscellanea Medica XVIII, pp. 65a-72b, 63a-64b, 75a-84a (early 1300s, France): middle collection, [4]. This copy has the famous image of “Trotula” holding an orb.

- Lat50: London, Wellcome Library, MS 548, Miscellanea Medica XXII, ff. 140r-145v (mid-1400s, Germany or Flanders): standard collection (selections), [5]

- Lat81: Oxford, Pembroke College, MS 21, ff. 176r-189r (late 1200s, England): early collection (LSM only); DOM (part), [6]

- Lat87: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS lat. 7056, ff. 77rb-86va; 97rb-100ra (mid-1200s, England or N. France): changing collection (Group B); TEM (original LSM), [7]

- Lat113: Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Pal. lat. 1304 (3rd ms of 5 in codex), ff. 38r-45v, 47r-48v, 46r-v, 51r-v, 49r-50v (mid-1200s, Italy): standard collection: [8].

Vernacular Manuscripts

French

- Fren1a: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.1.20 (1044), ff. 21rb-23rb (mid-1200s, England): Les secres de femmes, ed. in Hunt 2011 (cited above), [9] (see also Fren3 below)

- Fren2IIa: Kassel, Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt und Landesbibliothek, 4° MS med. 1, ff. 16v-20v (about 1430-75), [10]

- Fren3a: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.1.20 (1044), ff. 216r–235v, mid-1200s (England), ed. in Hunt, Anglo-Norman Medicine, II (1997), 76–107, [11]

Irish

- Ir1b: Dublin, Trinity College, MS 1436 (E.4.1), pp. 101–107 and 359b-360b (1400s): [12]. Search under the Library and then the individual shelfmark.

Italian

- Ital2a: London, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, MS 532, Miscellanea Medica II, ff. 64r-70v (about 1465): [13]

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |