Tsuda Umeko facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

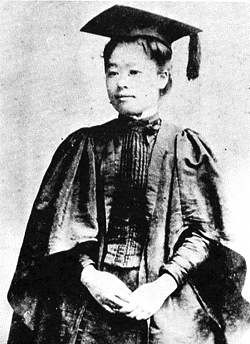

Tsuda Umeko

|

|

|---|---|

| 津田 梅子 | |

Tsuda Umeko

|

|

| Born |

Tsuda Ume (つだ・うめ)

December 31, 1864 Edo, Japan

|

| Died | August 16, 1929 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Other names | Ume Tsuda |

| Alma mater | Collegiate School Archer Institute Bryn Mawr College St Hilda's College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Educator |

| Era | Meiji period |

| Known for | A pioneer in education for women in Meiji period Japan |

| Children | none |

| Parent(s) | Tsuda Sen (father) Tsuda Hatsuko (mother) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Peeresses' School Tokyo Women's Normal School Joshi Eigaku Juku (founder) |

Tsuda Umeko (津田 梅子, born Tsuda Ume (つだ・うめ); December 31, 1864 – August 16, 1929) was a famous Japanese educator. She was a pioneer in education for women during Japan's Meiji period. This was a time when Japan was rapidly changing and adopting new ideas from the West.

Tsuda Umeko was born Tsuda Ume. Her first name, Ume, means "Japanese plum." She used the name Ume Tsuda while studying in the United States. In 1902, she changed her name to Umeko. She believed strongly that girls and women should have the same chances to learn as boys and men.

Contents

Early Life and Education in America

Tsuda Ume was born in Edo (now Tokyo) on December 31, 1864. She was the second daughter of Tsuda Sen and Hatsuko. Her father, Tsuda Sen, was a forward-thinking farmer. He strongly supported Japan becoming more like Western countries, including their education systems.

In 1871, Tsuda Sen was part of a project to develop Hokkaidō. He talked about the importance of Western education for both men and women.

Under the support of Kuroda Kiyotaka, Tsuda Ume's father volunteered her to join the Iwakura mission. This was a group of Japanese leaders and students who traveled to the United States and Europe.

At just six years old, Tsuda Ume was the youngest member of this important trip. She arrived in San Francisco in November 1871. She stayed in the United States to study for 12 years, until she was 18.

Living and Learning in Washington, D.C.

From December 1871, Tsuda lived in Washington, D.C. with Charles Lanman and his wife Adeline. Mr. Lanman was the secretary of the Japanese legation (a type of embassy). Since they had no children, they treated Tsuda like their own daughter.

She attended the Georgetown Collegiate School. There, she learned English and excelled in her studies. She won awards for her writing, math, and good behavior. After graduating, she went to the Archer Institute. This school was for the daughters of important politicians and government officials. Tsuda was very good at languages, math, science, and music, especially the piano. Besides English, she also studied Latin and French. About a year after arriving, Tsuda decided to become a Christian.

Returning to Japan and New Challenges

When Tsuda returned to Japan in 1882, she had almost forgotten her native Japanese. This made things difficult for a while. She also found it hard to adjust to Japanese society. Women in Japan at that time had a much lower position than men. Even her father, who was very modern in many ways, still held traditional views about women.

Tsuda was hired by Itō Hirobumi, a powerful leader, to teach his children. In 1885, she started working at the Peeresses' School. This was a school for the daughters of noble families. However, Tsuda was not happy there. She felt that education should not be limited to only noble families. She also disagreed with the school's goal, which was to train girls to be obedient wives and good mothers. She believed education should be about developing a person's mind and personality.

Her friend from America, Alice Mabel Bacon, helped her from 1888. Tsuda then decided to go back to the United States to continue her own education and learn more about women's education.

Second Time in the United States

Tsuda returned to the United States in 1889. She attended Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia until 1892. There, she studied biology and education. She also studied at St Hilda's College, Oxford in England.

During this second stay, Tsuda decided that other Japanese women should also have the chance to study abroad. She gave many speeches about the importance of education for Japanese women. She raised $8,000 to create a scholarship fund. This fund would help Japanese women study overseas.

Founding Tsuda College

After coming back to Japan, Tsuda Umeko taught again at the Peeresses' School. She also taught at the Tokyo Women's Normal School. Her salary was high for a woman at that time, and she held the highest position available to women. She wrote many papers and gave speeches about improving the lives of women.

In 1899, a new law required each area in Japan to have at least one public middle school for girls. However, these schools did not offer the same quality of education as boys' schools. In 1900, Tsuda Umeko decided to create a better option. With help from her friends, Princess Ōyama Sutematsu and Alice Bacon, she founded the Joshi Eigaku Juku (女子英学塾, Women's Institute for English Studies).

This school was located in Kōjimachi, Tokyo. Its goal was to give all women, no matter their family background, a chance to get a good liberal arts education. Tsuda Umeko changed her name from Ume to Umeko in 1902. The school often struggled with money, and Tsuda spent a lot of time raising funds. Because of her hard work, the school officially became recognized in 1903.

In 1905, Tsuda became the first president of the Japanese branch of the Tokyo YWCA, an organization that supports young women.

Later Life and Legacy

Tsuda Umeko's busy life eventually affected her health. She suffered a stroke. In January 1919, she moved to her summer home in Kamakura. She passed away there on August 16, 1929, at the age of 64, after a long illness. Her grave is on the grounds of Tsuda College in Kodaira, Tokyo.

The Joshi Eigaku Juku was renamed Tsuda Eigaku Juku in 1933. After World War II, it became Tsuda College. Today, it is still one of the most respected women's colleges in Japan.

Tsuda Umeko wanted to see big changes for women in society. However, she did not support the women's right to vote movement. Her main belief was that education should help each person develop their own intelligence and personality.

Tsuda Umeko's importance is still recognized today. She will be featured on new Japanese banknotes that will be printed in 2024.

See also

In Spanish: Tsuda Umeko para niños

In Spanish: Tsuda Umeko para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |