Tupi people facts for kids

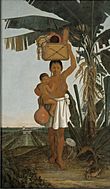

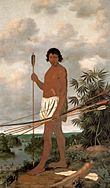

Albert Eckhout's painting of the Tupi

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,000,000 (historically), Potiguara 10,837, Tupinambá de Olivença 3,000, Tupiniquim 2,630, others extinct as tribes but blood ancestors to Pardo Brazilian population | |

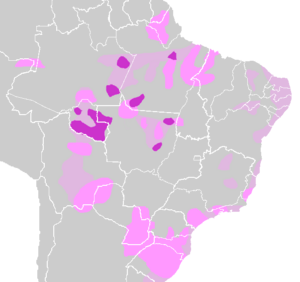

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central and Coastal Brazil | |

| Languages | |

| Tupi languages, later língua geral, much later Portuguese | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous, later Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Guaraní tribes |

The Tupi people were one of the biggest groups of native people in Brazil before Europeans arrived. They were part of the Tupi-Guarani language family. Experts think the Tupi first lived in the Amazon rainforest. About 2,900 years ago, they began moving south. They slowly settled along Brazil's Atlantic coast.

Today, many Tupi people have mixed with the Guaraní people. This mixing helped form the Tupi–Guarani languages. It's important to know that Guarani languages are different from the Tupian languages.

Contents

Tupi History and Culture

When the Portuguese first arrived in Brazil, the Tupi people lived along three-quarters of the country's coast. In 1500, it's thought that about 1 million Tupi people lived there. This was almost the same number of people living in Portugal at that time.

The Tupi were divided into different tribes. Each tribe had between 300 and 2,000 people. Some well-known Tupi tribes included the Tupiniquim, Tupinambá, Potiguara, Tabajara, Caetés, Temiminó, and Tamoios.

The Tupi were skilled farmers. They grew many different crops. These included cassava, corn, sweet potatoes, beans, peanuts, tobacco, squash, and cotton. Even though they spoke a common language, the Tupi tribes did not see themselves as one unified group.

Arrival of Europeans

When Portuguese settlers first met the Tupi people, they wrongly believed the Tupi had no religion. This belief led the Portuguese to try and convert the Tupi to Christianity. The settlers built special villages called aldeias for the Tupi. Their goal was to teach the Tupi European customs and religion.

Besides religious conversion, the Portuguese also needed workers. They used the Tupi people to grow and ship their goods. This need for labor led to the Tupi being enslaved. Sadly, working on plantations also caused the spread of deadly European diseases. The Tupi had no natural protection against these illnesses. These problems almost completely wiped out the Tupi people. Only a few small communities survived. Today, the remaining Tupi tribes live in special indigenous territories. Others have blended into Brazilian society.

Mixing Cultures: Cunhadismo

The Tupi people played a very important role in forming the Brazilian population. When Portuguese explorers arrived in Brazil in the 16th century, the Tupi were the first native group they met. Soon, Portuguese settlers and native women began to have children together. Portuguese colonists rarely brought women with them. This meant native women became key to the new Brazilian population.

A practice called "cunhadismo" started to spread in the colony. The word cunhadismo comes from the Portuguese word cunhado, meaning "brother-in-law." This was an old native tradition of welcoming strangers into their community. The Tupi offered a Portuguese man a native girl as a wife. If he accepted, he became like family to everyone in the tribe.

Polygyny, which is when a man has more than one wife, was common among South American native people. European settlers quickly adopted this practice. This way, a single European man could have many native wives, known as temericós.

Cunhadismo was also used to get workers. A Portuguese man with many temericós would have many native relatives. These relatives were encouraged to work for him. They often helped cut pau-brasil wood and carry it to ships on the coast.

This process led to a large mixed-race population called mamelucos. These mixed-race people helped settle Brazil. Without cunhadismo, Portuguese colonization would have been very difficult. There were very few Portuguese men and even fewer Portuguese women in Brazil. The growth of mixed-race people, born to native women, helped the Portuguese take over the land and establish their presence.

Tupi Influence in Brazil

Most of the Tupi population disappeared because of European diseases or slavery. However, many Brazilians today have Tupi ancestors on their mother's side. These people carried old Tupi traditions to many parts of the country.

Darcy Ribeiro, a famous writer, said that the first Brazilians looked more Tupi than Portuguese. Even the language they spoke was based on Tupi. This language was called Nheengatu or Língua Geral. It was a common language (a lingua franca) in Brazil until the 18th century.

The region of São Paulo was a major center for mixed-race people (Mamelucos). In the 17th century, these Mamelucos, known as Bandeirantes, traveled across Brazil. They went from the Amazon rainforest all the way to the far South. They were important for spreading Iberian culture deeper into Brazil. They also taught isolated native tribes the language of the colonizers. This language was not Portuguese yet, but Nheengatu. Nheengatu is still spoken in some parts of the Amazon today, even though Tupi-speaking natives didn't originally live there. The Bandeirantes from São Paulo brought Nheengatu to these areas in the 17th century.

The way of life for the "Old Paulistas" (people from São Paulo) was very similar to the natives. At home, they only spoke Nheengatu. Their farming, hunting, fishing, and fruit gathering also followed native traditions. The main differences between the "Old Paulistas" and the Tupi were that the Paulistas used clothes, salt, metal tools, weapons, and other European items.

As areas with strong Tupi influence became part of the market economy, Brazilian society slowly lost its Tupi characteristics. The Portuguese language became dominant, and Língua Geral almost disappeared. The simple native farming methods were replaced by European ones to increase exports.

However, Brazilian Portuguese still has many words from Tupi. Some examples are: mingau (a type of porridge), mirim (small), soco (punch), cutucar (to poke), tiquinho (a little bit), perereca (tree frog), and tatu (armadillo). Many names of animals like arara (macaw), jacaré (South American alligator), and tucano (toucan) also come from Tupi. Plant names like mandioca (manioc) and abacaxi (pineapple) are also from Tupi.

Many places and cities in modern Brazil have Tupi names. Examples include Itaquaquecetuba, Pindamonhangaba, Caruaru, and Ipanema. Some personal names like Ubirajara, Ubiratã, Moema, Jussara, Jurema, and Janaína are also Tupi. While Tupi surnames exist, they don't always mean someone has Tupi ancestors. Sometimes, they were adopted to show Brazilian pride.

The Tupinambá tribe is shown in a fictional way in the 1971 film How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman. Their name is also used in science: Tupinambis is a type of tegu lizard, which are well-known lizards in Brazil.

In 2006, a large offshore oil field was found near Brazil's coast. It was named the Tupi oil field to honor the Tupi people.

The Guaraní are another native group living in southern Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and northern Argentina. They speak different Guaraní languages. However, these languages are in the same language family as Tupi.

Notable Tupi People

- Catarina Paraguaçu (1528—1586)

- Araribóia, who founded the city of Niterói, Brazil

- Cunhambebe

See also

In Spanish: Pueblos tupíes para niños

In Spanish: Pueblos tupíes para niños

- José de Anchieta

- Língua Geral

- Manuel da Nóbrega

- Tupian languages