Citizenship of the United States facts for kids

United States citizenship is a special legal status that gives people in the United States certain rights, responsibilities, and benefits. It's like being a full member of the country. This status is based on the Constitution and U.S. laws.

Being a U.S. citizen means you have important rights. These include freedom of speech, the right to a fair legal process, the right to vote (though not all citizens can vote in every election, like those in Puerto Rico), and the freedom to live and work anywhere in the U.S. You can also get help from the federal government if needed.

There are two main ways to become a U.S. citizen:

- Birthright citizenship: This means you are a citizen if you are born in the U.S. or, in some cases, if you are born outside the U.S. to a U.S. citizen parent.

- Naturalization: This is a process where a person who is a legal immigrant applies to become a citizen and is approved.

The idea of birthright citizenship comes from the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in the Constitution. It says:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

The process of naturalization is set by Congress, as stated in Article One of the Constitution.

The U.S. allows people to have citizenship in more than one country, which is called multiple citizenship. If someone from another country becomes a U.S. citizen, they can often keep their first citizenship. Also, a U.S. citizen who becomes a citizen of another country can usually keep their U.S. citizenship. However, they must promise loyalty to the U.S. when they become a citizen. A U.S. citizen can also choose to give up their U.S. citizenship through a formal process at a U.S. embassy.

Contents

- What are the Rights, Duties, and Benefits of a Citizen?

- Taking Part in Civic Life

- Dual Citizenship

- History of Citizenship in the U.S.

- Birthright Citizenship

- Naturalized Citizenship

- Honorary Citizenship

- Corporate Citizenship

- Citizenship vs. Nationality

- Giving Up Citizenship

- Revoking Citizenship

- Images for kids

What are the Rights, Duties, and Benefits of a Citizen?

Important Rights of Citizens

- Freedom to live and work: U.S. citizens can live and work anywhere in the United States. While some non-citizens, like permanent residents, have similar rights, citizens cannot have this right taken away easily. For example, permanent residents might be deported if they commit a serious crime, but citizens cannot.

- Freedom to enter and leave the U.S.: Citizens can freely enter and leave the United States. Unlike permanent residents, citizens don't have to live in the U.S. to keep their status. They can leave for any amount of time and return whenever they want.

- Voting: Only citizens can vote in federal elections in all 50 states and District of Columbia. Some states might prevent citizens who have committed serious crimes from voting. The Constitution says states cannot stop citizens from voting because of their race, gender, or age (if they are 18 or older). Citizens are not forced to vote.

- Running for public office: The Constitution requires that members of the United States House of Representatives must have been citizens for seven years. Senators must have been citizens for nine years. To be president of the United States or vice president, a person must be a "natural born Citizen" and have lived in the U.S. for fourteen years. There are also age requirements for these jobs.

- Applying for federal jobs: Many jobs in the U.S. government require you to be a U.S. citizen.

Important Duties of Citizens

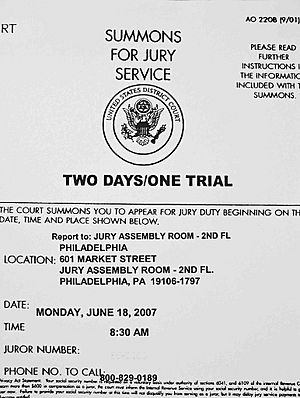

- Jury duty: Only citizens can be called to jury duty. This means serving on a jury in court. This is often seen as the main difference in duties between citizens and non-citizens.

- Military participation: While military service is not currently required, in the past, men were sometimes called to serve in the military, especially during wars. Today, the United States Armed Forces is made up of volunteers. However, all male U.S. citizens and male permanent residents must register with the Selective Service System when they turn 18. They could be called to serve if there's a future draft.

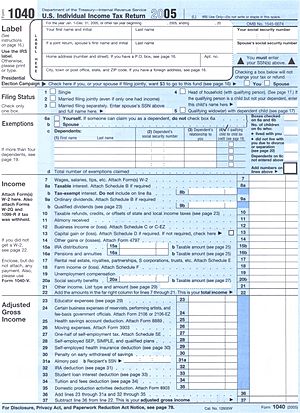

- Taxes: Most people in the U.S. must file a federal income tax return. U.S. citizens must pay federal income tax on their earnings no matter where they live in the world.

- Census: Every ten years, the U.S. government counts everyone living in the country in a United States census. All residents are required to answer the census questions.

Benefits of Being a Citizen

- Help from U.S. embassies abroad: If you are traveling outside the U.S. and get into trouble, like being arrested, you can ask to speak to someone from the U.S. Embassy or Consulate. They can help you find a local lawyer or provide other support.

- Sponsoring relatives: Being a U.S. citizen makes it easier to help family members from other countries get visas to come and live in the U.S.

- Passing on citizenship: Generally, children born outside the U.S. to two U.S. citizen parents automatically become U.S. citizens. If only one parent is a U.S. citizen, there are certain rules about how long that parent must have lived in the U.S. for the child to get citizenship.

- Protection from deportation: Once you become a naturalized U.S. citizen, you cannot be deported from the country.

- Other recognitions: The U.S. government sometimes honors naturalized citizens for their achievements. For example, the "Outstanding American by Choice" Award recognizes people like Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel and former PepsiCo CEO Indra K. Nooyi.

Taking Part in Civic Life

Civic participation means taking an active role in your community and country. In the United States, you are not required to attend town meetings, join a political party, or even vote. However, a great benefit of becoming a citizen is being able to "participate fully in the civic life of the country." This means your voice matters in politics.

Some people believe that if citizens don't get involved in politics, it's bad for democracy. Others think that if most people are not too involved, it can lead to a calmer political situation. They argue that if things are going well, people might not feel the need to be highly active.

Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship means a person is considered a citizen by more than one country. It is possible for a U.S. citizen to have dual citizenship. This can happen in different ways:

- If you are born in the U.S. to a parent who is a citizen of another country.

- If you are born in another country to U.S. citizen parents.

- If your parents are citizens of different countries.

When someone becomes a naturalized U.S. citizen, they must promise to give up any loyalty to other countries during the naturalization ceremony. However, the State Department says that a U.S. citizen can become a citizen of another country without losing their U.S. citizenship.

If you have dual citizenship, you must use your U.S. passport when entering or leaving the United States. The Supreme Court has ruled that a U.S. citizen does not lose their citizenship just by voting in a foreign election or becoming a citizen of another country, unless they truly intend to give up their U.S. citizenship.

History of Citizenship in the U.S.

In the early days of the United States, citizenship meant men actively working together to solve local problems, like in New England town hall meetings. People met often to discuss local issues and make decisions. These meetings were seen as the "earliest form of American democracy."

Over time, the idea of citizenship changed. It became less about active participation and more about a legal status with specific rights and benefits. While direct civic participation became less common, the right to be a citizen expanded. At first, only white men who owned property could be citizens. Later, black men and then women were also included.

The Supreme Court confirmed in 1898 that anyone born in the U.S. becomes a citizen, even if their parents are from another country. This was based on the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Equal Nationality Act of 1934 made it easier for children born outside the U.S. to a U.S. citizen mother and a non-citizen father to become citizens. It also sped up the naturalization process for non-citizen husbands of American women. This law helped make citizenship rules more equal for men and women.

Birthright Citizenship

Most people become U.S. citizens at birth if they are born within the territory of the United States. The U.S. territory includes the 50 U.S. states, District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Mariana Islands, the United States Virgin Islands, and the Palmyra Atoll.

The Fourteenth Amendment, added in 1868, clearly defined who is a citizen: "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." This means almost all babies born in the U.S. are citizens, no matter what their parents' citizenship or immigration status is. Exceptions are usually for children of foreign diplomats.

Children born outside the U.S. to U.S. citizens are also usually U.S. citizens. This is called birthright citizenship by parentage.

Even though people born in the U.S. are citizens from birth, they are considered minors until age 18. This means they cannot vote or hold public office until then. When they turn 18, they automatically become full citizens without any special ceremony.

Naturalized Citizenship

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to create rules for "Naturalization." This is how people who were not born in the U.S. can become citizens.

Who is in Charge?

The agency that handles new citizens is called the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS. It is part of the Department of Homeland Security. USCIS helps people apply for citizenship and processes their cases.

How to Become a Citizen (Pathways)

People who want to become U.S. citizens must meet certain requirements:

- They usually need to have been permanent residents for five years (or three years if married to a U.S. citizen).

- They must have "good moral character," meaning no serious criminal history.

- They need to understand the Constitution.

- They must be able to speak and understand English, unless they are elderly or have a disability.

- They must pass a citizenship test. This test asks questions about American history and government. You need to answer six out of ten questions correctly to pass.

Here are some ways people can become permanent residents and then apply for citizenship:

- Diversity Visa lottery: This program allows people from certain countries to apply for a chance to become a permanent resident.

- Military service: People who serve in the United States Military can often become citizens faster. In 2002, President Bush made it possible for service members to apply for citizenship right away, instead of waiting three years. This option is not open to people who are in the U.S. without permission.

- Grandparent rule: In some cases, children born outside the U.S. to a U.S. citizen parent can use the time their U.S. citizen grandparent lived in the U.S. to help them qualify for citizenship. This rule was updated in 2000.

High Demand for Citizenship

Becoming a U.S. citizen is very valuable. Many people want to become citizens, and millions have applied over the years. The number of applications can change based on the economy and fees.

The fees for applying for naturalization have increased over time. In 1989, it was US$60, and by 2014, it was US$640. Some people believe these fees make it harder for some immigrants to become citizens.

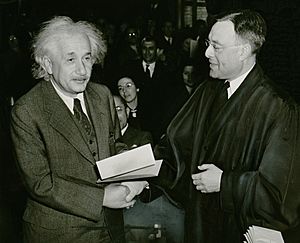

Citizenship Ceremonies

The process of becoming a citizen often ends with a special ceremony. Many new citizens are sworn in during Independence Day celebrations. Most ceremonies happen at USCIS offices, but sometimes they are held in special places like Arlington National Cemetery to honor the country. During the ceremony, applicants take an oath of allegiance to the United States.

Honorary Citizenship

The title of "Honorary Citizen of the United States" is very rare. It has only been given eight times by an act of Congress or by the president. Famous people who have received this honor include Winston Churchill and Mother Teresa.

Sometimes, non-citizen immigrants who died fighting for the U.S. military have been given the title of U.S. citizen after their death. This is different from honorary citizenship.

Corporate Citizenship

The term "corporate citizenship" can mean a few things. Since companies are seen as "persons" in the eyes of the law, they can sometimes be thought of as citizens. For example, an airline might want to be treated as an "American air carrier" to get support from the U.S. government when dealing with other countries.

"Corporate citizenship" can also mean when a company shows support for social issues and the environment. This can help the company's reputation.

Citizenship vs. Nationality

The law makes a difference between "citizenship" and "nationality" in the U.S. All U.S. citizens are also U.S. nationals. But not all U.S. nationals are U.S. citizens. This means some people can be a national of the U.S. without being a full citizen.

Non-Citizen Nationals

Currently, American Samoa is the only U.S. territory where babies born there become non-citizen U.S. nationals at birth. This means they are loyal to the U.S. and protected by it, but they don't have all the same rights as citizens.

People born in Puerto Rico, Guam, the United States Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands are U.S. citizens at birth because Congress passed laws giving them this status.

Differences Between Citizens and Non-Citizen Nationals

U.S. citizenship gives more rights than non-citizen U.S. nationality. For example, non-citizen U.S. nationals can live and work in the U.S. without limits, but they cannot vote in federal or state elections.

Non-citizen U.S. nationals can apply to become U.S. citizens through naturalization. They have to meet similar requirements as foreign nationals, like paying a fee, passing a "good moral character" check, and taking an English and civics test. However, they don't need to have a permanent residency to apply.

The U.S. passport given to non-citizen nationals states that the person is a "United States national and not a United States citizen."

Giving Up Citizenship

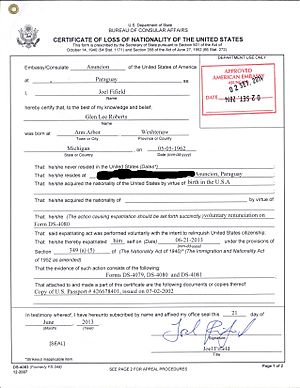

U.S. citizens can choose to give up their citizenship. This means they give up the right to live in the U.S. and all other rights and responsibilities of being a citizen. This process is called "relinquishment." One way to do this is by formally "renouncing" citizenship by swearing an oath at a U.S. embassy or consulate.

When someone gives up their citizenship, a U.S. official checks to make sure they are doing it willingly and understand what it means. The U.S. government suggests that people have another citizenship before giving up their U.S. citizenship, but it is possible to become stateless. There is a fee for this process, and some people might also have to pay an expatriation tax.

Revoking Citizenship

In some situations, a person's citizenship can be taken away. For example, if a naturalized citizen hid important information or lied during their application, their naturalization might be canceled.

A citizen does not lose U.S. citizenship just by taking a job in a foreign government. However, if they hold a very high position in a foreign government, their U.S. consular rights might be limited.

From 1922 to 1940, a U.S. citizen woman could lose her citizenship simply by marrying a non-citizen. This rule was later changed.

Images for kids

In Spanish: Nacionalidad estadounidense para niños

In Spanish: Nacionalidad estadounidense para niños

- Accidental American

- Anchor baby

- Birth tourism

- Birthright citizenship in the United States of America

- Birthright generation

- Citizenship (general discussion for all nations)

- Citizenship education

- DREAM Act

- History of citizenship

- Jus soli

- Natural born citizen of the United States

- Undocumented students in the United States

- Undocumented youth in the United States

- United States nationality law