History of immigration to the United States facts for kids

The history of people moving to the United States tells the story of how different groups came to live in America, from the early colonies to today. The United States has seen many waves of immigrants, especially from Europe, and later from Asia and Latin America.

In the past, many immigrants from the colonial era paid for their trip across the ocean by becoming indentured servants. This meant they worked for a new employer for a set number of years. Starting in the late 1800s, rules were made to limit immigration from China and Japan. In the 1920s, strict limits were put in place, but people fleeing war or danger could still come. These strict limits ended in 1965. Today, most new immigrants come from Asia and Central America.

People's feelings about new immigrants have changed a lot over time, from welcoming to sometimes unwelcoming, since the late 1700s. Recent talks often focus on the border with Mexico and on young people called "Dreamers." These are people who were brought to the U.S. as children without papers and have lived almost their whole lives here.

Contents

Early American Settlements

In 1607, the first successful English settlement was built in Jamestown, Virginia. When people found out that tobacco was a very profitable crop, many large farms were started along the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia and Maryland.

This was the start of the first and longest period of immigration, which lasted until the American Revolution in 1775. During this time, the small English settlements grew into British America. Most immigrants came from Northern Europe, mainly from Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands. The British were the largest group to arrive and stayed under British rule. More than 90% of these early immigrants became farmers.

Many young men and women came alone as indentured servants. Their trip was paid for by employers in the colonies who needed help on farms or in shops. Indentured servants received food, housing, clothes, and training, but no wages. After their service (usually around age 21 or after seven years), they were free to marry and start their own farms.

Seeking Freedom in New England

In 1620, about one hundred English Pilgrims came to the New World looking for religious freedom. They built a small settlement near Plymouth, Massachusetts. Many thousands of English Puritans arrived between 1629 and 1640. They mostly came from eastern England and settled in Boston, Massachusetts and nearby areas. They wanted to create a land dedicated to their religion.

The first colonies in New England were Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire. These were built along the northeast coast. Large-scale immigration to this area mostly stopped before 1700.

The New England colonists were often more educated and lived in towns compared to other settlers. They included many skilled farmers, traders, and craftspeople. They started Harvard, the first university, in 1635 to train their religious leaders. They often lived in small villages for support and religious activities. Their main ways to earn money were shipbuilding, trade, farming, and fishing. New England had a healthy climate with cold winters that killed disease-carrying insects. This, along with small villages and plenty of food, led to low death rates and high birth rates. The population grew quickly because families had many children.

Dutch Settlers in New York

The Dutch colonies were set up by the Dutch East India Company around 1626. They were built along the Hudson River in what is now New York state. Rich Dutch landowners called patroons created large estates along the Hudson River. They brought in farmers who became renters. Others set up busy trading posts to trade with Native Americans. They also started cities like New Amsterdam (which is now New York City) and Albany, New York.

After the British took over the colony and renamed it New York, more people arrived. These included Germans from the Palatinate region and Yankees from New England.

Middle Colonies: A Mix of Cultures

Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware were known as the Middle Colonies. Pennsylvania was settled by Quakers from Britain. Later, many Ulster Scots (from Northern Ireland) settled on the frontier. Many German Protestant groups, including the German Palatines, also came. Earlier, New Sweden had small settlements on the lower Delaware River, with immigrants from Sweden and Finland. These smaller colonies were taken over by 1676.

The middle colonies spread west from New York City and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. New Amsterdam/New York had people from many different nations. It became a major trading center after 1700. From about 1680 to 1725, Quakers mostly controlled Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, a busy trade center, was run by wealthy Quakers. There were also many small farming and trading communities, with a strong German presence in the Delaware River valley.

After 1680, when Pennsylvania was founded, many more settlers arrived in the middle colonies. Many Protestant groups were drawn by the promise of religious freedom and cheap, good land. About 60% of these settlers were British and 33% were German. By 1780, about 27% of New York's population were descendants of Dutch settlers. About 6% were African, and the rest were mostly English with a mix of other Europeans. New Jersey and Delaware had mostly British people. They also had about 7–11% German descendants, about 6% African people, and a small group of Swedish descendants from New Sweden.

Life on the Frontier

The fourth main area of settlement was the western frontier. This was in the inland parts of Pennsylvania and the southern colonies. It was mostly settled between 1717 and 1775 by Presbyterian farmers. They came from the border areas of North England, Scotland, and Ulster. They were escaping hard times and religious unfairness. Between 250,000 and 400,000 Scots-Irish people moved to America in the 1700s.

The Scots-Irish quickly became the main culture in the Appalachian Mountains, from Pennsylvania to Georgia. These were areas where later censuses showed many people had "American" ancestry. Scots-Irish American immigrants were people from southern Scotland who had first settled in Ireland. They were mostly Presbyterian and very independent. They arrived in large numbers in the early 1700s. They often chose to settle in the back country and on the frontier. Here, they mixed with English settlers who had been there for a generation or more. They liked the very cheap land and the freedom from established governments that frontier settlements offered.

Southern Colonies: Farming and Challenges

The mostly farming-based Southern English colonies first had very high death rates for new settlers. This was due to diseases like malaria and yellow fever, and fights with Native Americans. But a steady flow of new immigrants, mostly from Central England and the London area, kept the population growing. By 1630, many Native Americans had already left the first settlement areas. This was because of major outbreaks of diseases like measles, smallpox, and bubonic plague that started decades before Europeans arrived in large numbers. Smallpox was the biggest killer, arriving in the New World around 1510–1530.

At first, the large farms (plantations) in these colonies were mostly owned by friends of the British governors. A group of Scottish Highlanders who spoke Gaelic created a settlement at Cape Fear in North Carolina. This group kept its own culture until the mid-1700s, when it was absorbed by the larger English culture. Many settlers from Europe arrived as indentured servants. Their trip was paid for in exchange for five to seven years of work. They received free room, food, clothes, and training, but no cash wages. After their service ended, many of these former servants started small farms on the frontier.

By the early 1700s, the forced movement of African slaves became a big part of the population in the Southern colonies. Between 1700 and 1740, most new people arriving in these colonies were Africans. In the late 1700s, the population of that region was about 55% British, 38% black, and 7% German. In 1790, 42% of the people in South Carolina and Georgia were of African origin. Before 1800, growing tobacco, rice, and indigo on plantations in the Southern colonies relied heavily on the work of slaves from Africa. The Atlantic slave trade to mainland North America stopped during the Revolution. It was made illegal in most states by 1800 and across the nation in 1808, though some slaves were still brought in illegally.

What Colonial Life Was Like

Even though the thirteen colonies were settled in different ways and by different people, they had many things in common. Most were started and paid for by private British settlers or families. They used free enterprise without much help from the King or Parliament. Most businesses were small and privately owned. They had good credit in America and England, which was important because they often didn't have much cash.

Most settlements were quite independent from British trade. They grew or made almost everything they needed. The average cost of imports per household was very low. Most settlements included whole family groups with several generations living together. The population was mostly rural, with about 80% owning the land they lived and farmed on. After 1700, as the Industrial Revolution grew, more people started moving to cities, just like in Britain.

At first, Dutch and German settlers spoke their own languages. But English became the main language for business. Governments and laws mostly copied English ways. The main British idea that was left behind was the aristocracy, which was almost completely missing. The settlers usually set up their own courts and elected governments. This way of self-rule became so strong that for the next 200 years, almost all new settlements quickly set up their own governments after people arrived.

After the colonies were established, their population grew mostly from families already living there. The number of foreign-born immigrants rarely went over 10%. The last major colonies settled mainly by new immigrants were Pennsylvania (after the 1680s), the Carolinas (after 1663), and Georgia (after 1732). Even in these places, most immigrants came from England and Scotland, except for Pennsylvania's large German group. In other areas, people moving from one American colony to another provided almost all the settlers for new colonies or states. Populations grew by about 80% every 20 years, with a natural growth rate of 3% per year.

More than half of all new British immigrants in the South first arrived as indentured servants. These were mostly poor young people who couldn't find work in England or pay for their trip to America. Also, about 60,000 British convicts who had committed minor crimes were sent to the British colonies in the 1700s.

Other Early Settlements

Spanish Influence

Even though Spain built a few forts in Florida, like San Agustín (now Saint Augustine) in 1565, they sent few settlers there. Spaniards moving north from Mexico founded San Juan on the Rio Grande in 1598 and Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1607–1608. The settlers had to leave for 12 years (1680–1692) because of the Pueblo Revolt before returning.

Spanish Texas existed from 1690 to 1821. During this time, Texas was a colony separate from New Spain. In 1731, people from the Canary Islands (called "Isleños") arrived to establish San Antonio. Most of the few hundred Spanish settlers in Texas and New Mexico during the colonial period were Spaniards and criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas). California, New Mexico, and Arizona all had Spanish settlements. In 1781, Spanish settlers founded Los Angeles.

When these former Spanish colonies joined the United States, there were about 10,000 Californios in California and about 4,000 Tejanos in Texas. New Mexico had 47,000 Spanish settlers in 1842, but Arizona was only sparsely settled. Not all these settlers were of European background. Like in other American colonies, new settlements used a "casta" system. This was a mix of white, Native, and mestizo (mixed heritage) people, though all spoke Spanish.

French Settlements

In the late 1600s, French explorers set up bases along the Saint Lawrence River, Mississippi River, and Gulf Coast. Trading posts, forts, and cities in the interior were spread out. The city of Detroit was the third-largest settlement in New France. New Orleans grew when thousands of French-speaking refugees from the Acadia region came to Louisiana. They settled mostly in Southwest Louisiana, an area now called Acadiana. Their descendants are known as Cajuns and still live mostly in the coastal areas. About 7,000 French-speaking immigrants settled in Louisiana during the 1700s.

Who Lived in America in 1790?

Before 1790, about 950,000 immigrants came to the United States. By 1790, the total population was about 3.9 million people. Most of the people living in the U.S. at that time had British roots.

Here's a quick look at where people came from before 1790 and how many people of those backgrounds lived in the U.S. in 1790:

- Africa: 360,000 immigrants, 757,000 people in 1790 (mostly enslaved).

- England: 230,000 immigrants, 2,100,000 people in 1790.

- Ulster Scots-Irish: 135,000 immigrants, 300,000 people in 1790.

- Germany: 103,000 immigrants, 270,000 people in 1790.

- Scotland: 48,500 immigrants, 150,000 people in 1790.

- Netherlands: 6,000 immigrants, 100,000 people in 1790.

- France: 3,000 immigrants, 15,000 people in 1790.

The total population in 1790 was about 3.9 million people, not counting Native Americans. About 86% of the white population had British ancestors. Germans made up about 9%, Dutch 3.4%, and French 2.1%. Black people made up about 19.3% of the U.S. population. The population generally doubled every 23 years, mostly because families had many children. This steady growth pushed the U.S. frontier all the way to the Pacific Ocean by 1848.

Immigration from 1790 to the 1860s

Not counting enslaved Africans, there wasn't much immigration from 1770 to 1830. Some people even left the U.S. for Canada, including about 75,000 Loyalists (people who supported Britain during the American Revolution).

Large-scale immigration started again in the 1830s and 1850s. Many people came from Britain, Ireland, and Germany. Most were drawn by cheap farmland. Some were skilled workers who found jobs in the new factories. Irish Catholics were often unskilled workers who helped build canals and railroads. They settled in cities. Many Irish went to textile mill towns in the Northeast or became dockworkers in port cities. Half of the Germans went to farms, especially in the Midwest, while the other half became craftspeople in cities.

Some Americans at the time were against new immigrants, especially Irish and German Catholics. This feeling was called "Nativism." It became strong for a short time in the mid-1850s with a group called the Know Nothing party. Most Catholics and German Lutherans joined the Democratic Party. Most other Protestants joined the new Republican Party. During the American Civil War, different ethnic groups supported the war. Many soldiers on both sides came from immigrant communities.

Immigration slowly increased. In the 1820s, it more than doubled to 143,000 people. Between 1831 and 1840, it quadrupled to 599,000. This included about 207,000 Irish, 152,000 Germans, and 76,000 British.

From 1841 to 1850, immigration almost tripled again, with 1,713,000 immigrants. This included at least 781,000 Irish, 435,000 Germans, and 267,000 British. The Irish came in huge numbers because of the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1849). They left their homeland to escape poverty and death. The failed revolutions of 1848 also brought many thinkers and activists to the U.S. Bad times in Europe pushed people out, while land, relatives, freedom, and jobs in the U.S. pulled them in.

By 1850, about 90% of the U.S. population was born in America. The first large wave of Catholic immigrants started in the mid-1840s. This changed the population from about 95% Protestant to about 90% Protestant by 1850.

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican War. This treaty gave U.S. citizenship to about 60,000 Mexican residents in the New Mexico Territory and 10,000 in Mexican California. About 2,500 other foreign-born residents in California also became U.S. citizens.

In 1849, the California Gold Rush attracted 100,000 people hoping to find gold. They came from the Eastern U.S., Latin America, China, Australia, and Europe. California became a state in 1850 with a population of about 90,000.

Immigration from 1850 to 1930

Between 1850 and 1930, about 5 million Germans moved to the United States. The most Germans arrived between 1881 and 1885, when a million settled mainly in the Midwest. Between 1820 and 1930, 3.5 million British and 4.5 million Irish came to America. Before 1845, most Irish immigrants were Protestants. After 1845, Irish Catholics started arriving in large numbers, mostly because of the Irish Potato Famine.

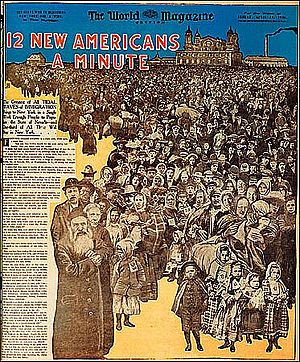

After 1880, large steamships replaced sailing ships. This made tickets cheaper and travel easier for immigrants. Also, new railroads in Europe made it simpler for people to reach ports to board ships. At the same time, farming improvements in Southern Europe and the Russian Empire meant there were too many workers. Young people, aged 15 to 30, were the most common newcomers. This wave of migration was huge, with nearly 25 million Europeans making the long journey. Italians, Greeks, Hungarians, Poles, and others who spoke Slavic languages made up most of this migration. Between 2.5 and 4 million Jewish people were among them.

Where Immigrants Settled

Each group had its own way of migrating. This included the balance of men and women, how long they stayed, their reading and writing skills, and the number of adults versus children. But they all had one main thing in common: they moved to cities. They became the main workforce for U.S. industries like steel, coal, cars, textiles, and clothing. This helped the United States become one of the world's biggest economic powers.

Their large numbers in cities, and perhaps a dislike of foreigners, led to a second wave of organized anti-immigrant feelings. By the 1890s, many Americans, especially those who were well-off, white, and native-born, thought immigration was a serious danger to the country. In 1893, a group formed the Immigration Restriction League. This group and others like it started pushing Congress to severely limit foreign immigration.

Irish and German Catholic immigration was opposed in the 1850s by the Nativist/Know Nothing movement. This movement started in New York in 1843. It grew because people feared the country was being overwhelmed by Catholic immigrants. These immigrants were often seen as against American values and controlled by the Pope in Rome. The movement was active mainly from 1854 to 1856. It tried to stop immigration and limit who could become a citizen, but it didn't have much success.

Many European immigrants joined the Union Army during the Civil War. This included 177,000 born in Germany and 144,000 born in Ireland. This was a full 16% of the Union Army. Many Germans saw similarities between slavery in the U.S. and serfdom in their home country.

Between 1840 and 1930, about 900,000 French Canadians left Quebec to move to the United States. They mainly worked in New England. About half of them later returned to Canada. This was a huge number, considering Quebec's population was only about 892,000 in 1851. Many Americans today who say they have French ancestry have ancestors who came from French Canada.

Soon after the U.S. Civil War, some states started making their own immigration laws. But in 1875, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that immigration was a federal responsibility.

In 1875, the U.S. passed its first national immigration law, the Page Act of 1875. This law, also called the Asian Exclusion Act, made it illegal to bring in Asian contract workers and anyone considered a criminal in their home country.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law stopped all Chinese laborers from entering the country. It greatly reduced the number of Chinese immigrants allowed into the U.S. for 10 years. The law was renewed in 1892 and 1902. During this time, some Chinese migrants entered the United States illegally through the border with Canada.

Before 1890, individual states, not the federal government, controlled immigration. The Immigration Act of 1891 created a Commissioner of Immigration in the Treasury Department. The Canadian Agreement of 1894 extended U.S. immigration rules to Canadian ports.

The Dillingham Commission was set up by Congress in 1907. It looked into how immigration affected the country. The Commission's large study found that most immigrants were now coming from Southern Europe and Russia, instead of Central, Northern, and Western Europe.

The 1910s were the peak years for Italian immigration to the United States. Over two million Italians came during these years, with a total of 5.3 million between 1880 and 1920. About half of them later returned to Italy after working in the U.S. for about five years.

About 1.5 million Swedes and Norwegians immigrated to the United States during this time. They came because of opportunities in America and poverty and religious oppression in their home country. This was about 20% of the total population of Sweden-Norway at that time. They settled mainly in the Midwest, especially Minnesota and the Dakotas. Fewer Danes immigrated because their economy was better. After 1900, many Danish immigrants were Mormon converts who moved to Utah.

Over two million people from Central Europe, mainly Catholics and Jews, immigrated between 1880 and 1924. People of Polish background are the largest Central European group in the United States after Germans. Fewer people from Eastern Orthodox groups immigrated.

Lebanese and Syrian immigrants started settling in large numbers in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Most of these immigrants were Christians, but smaller numbers of Jews, Muslims, and Druze also settled. Many lived in New York City's Little Syria and in Boston. In the 1920s and 1930s, many of these immigrants moved West. Detroit received many Middle Eastern immigrants, as did many Midwestern areas where Arabs worked as farmers.

Congress passed a literacy requirement in 1917. This was meant to reduce the number of low-skilled immigrants entering the country.

Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921, followed by the Immigration Act of 1924. These laws effectively banned all immigration from Asia. They also set limits for the Eastern Hemisphere. No more than 2% of people from any nationality, based on the 1890 census, were allowed to immigrate to America.

The "New Immigration"

"New immigration" was a term from the late 1880s. It referred to the large number of Catholic and Jewish immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. These areas had sent few immigrants before. Most of them came through Ellis Island in New York, so the Northeast became a major place for them to settle.

Some people worried that the new arrivals didn't have the skills to fit into American culture. This made people wonder if the U.S. was still a "melting pot" or if it had just become a "dumping ground." Many older Americans worried about negative effects on the economy, politics, and culture. One big idea was to require a literacy test. Applicants would have to be able to read and write in their own language to be allowed in. In Southern and Eastern Europe, fewer people could read because governments didn't invest in schools.

Immigration from 1920 to 2000

Immigration limits were put in place little by little in the late 1800s and early 1900s. But right after World War I (1914–18) and into the early 1920s, Congress changed the country's main immigration policy. The National Origins Formula of 1921 (and its final version in 1924) not only limited the number of immigrants allowed into the United States but also gave spots based on quotas for each country. This law was so strict that the number of immigrants coming to the U.S. between 1921 and 1922 dropped by almost 500,000. This complicated law mostly favored immigrants from Central, Northern, and Western Europe. It limited numbers from Eastern and Southern Europe and gave no quotas to Asia. However, close family members could still come.

The law did not include Latin America in the quota system. Immigrants could move quite freely from Mexico, the Caribbean (like Jamaica, Barbados, and Haiti), and other parts of Central and South America.

The period of the 1924 law lasted until 1965. During those 40 years, the United States started to allow a limited number of refugees on a case-by-case basis. Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany before World War II, Jewish Holocaust survivors after the war, and non-Jewish people fleeing Communist rule in Central Europe and the Soviet Union found safety in the U.S. Hungarians seeking refuge after their failed uprising in 1956 and Cubans after the 1960 revolution also found a haven. These groups were allowed in when their difficult situations touched the hearts of Americans. But the main immigration law stayed the same.

Equal Nationality Act of 1934

This law allowed foreign-born children of American mothers and foreign fathers to apply for American citizenship for the first time. This was if they had entered America before age 18 and lived there for five years. It also made the process quicker for foreign husbands of American wives to become citizens. This law made the rules for leaving the country, immigrating, becoming a citizen, and returning equal for women and men. However, it did not apply to past cases and was changed by later laws.

Filipino Immigration

In 1934, the Tydings–McDuffie Act gave the Philippines independence on July 4, 1946. Until 1965, strict national origin quotas greatly limited immigration from the Philippines. In 1965, after the immigration law was changed, many Filipinos began to immigrate. By 2004, a total of 1,728,000 Filipinos had immigrated.

Immigration After World War II

In 1945, the War Brides Act allowed foreign-born wives of U.S. citizens who had served in the U.S. Armed Forces to immigrate. In 1946, this act was expanded to include the fiancés of American soldiers. Also in 1946, the Luce–Celler Act gave people from the newly independent nation of The Philippines and Asian Indians the right to become naturalized citizens. The immigration limit was set at 100 people per year per country.

After World War II, "regular" immigration quickly increased under the official quota system. Refugees from war-torn Europe began coming to the U.S. After the war, there were jobs for almost everyone who wanted one. Many women who had worked during the war went back home. From 1941 to 1950, 1,035,000 people immigrated to the U.S. This included 226,000 from Germany, 139,000 from the UK, 171,000 from Canada, 60,000 from Mexico, and 57,000 from Italy.

The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 finally allowed people displaced by World War II to immigrate. About 200,000 Europeans and 17,000 orphans were initially allowed to immigrate outside of the regular quotas. President Harry S. Truman signed the first Displaced Persons (DP) act on June 25, 1948, allowing 200,000 DPs to enter. A second act in 1950 allowed another 200,000. This program required sponsors for all immigrants. In total, nearly 600,000 refugees were allowed into the country outside the quota system.

The 1950s: New Challenges and Changes

In 1950, after the start of the Korean War, the Internal Security Act stopped Communists from entering the U.S. This was because they might do things that would harm the country's safety. Many Koreans began immigrating in 1965, with 848,000 by 2004.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 kept the national-origins quota system from 1924. It limited total annual immigration to a very small percentage of the U.S. population in 1920, or 175,455 people. This law did not apply to spouses and children of U.S. citizens or people born in the Western Hemisphere. In 1953, the Refugee Relief Act gave refugee status to non-Europeans.

In 1954, "Operation Wetback" forced thousands of illegal immigrants to return to Mexico. Between 1944 and 1954, the number of illegal immigrants from Mexico grew by 6,000 percent. It's thought that over a million workers had crossed the Rio Grande illegally before this operation. Cheap labor meant lower wages for American farmworkers. It also led to more violations of labor laws and discrimination. The U.S. Border Patrol, with help from other authorities and the military, started a large operation to find and remove illegal immigrants. Many people left voluntarily. The program was eventually stopped because of concerns about how it was carried out. People of Mexican descent complained that police stopped anyone who "looked Mexican" and used harsh methods, including deporting American-born children who were citizens.

The failed Hungarian Revolution of 1956 allowed many refugees to escape before the Soviets crushed it. By 1960, 245,000 Hungarian families were allowed into the U.S. From 1950 to 1960, the U.S. had 2,515,000 new immigrants. This included 477,000 from Germany, 185,000 from Italy, 300,000 from Mexico, and 377,000 from Canada.

The 1959 Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro caused many upper and middle-class Cubans to leave their country. By 1970, 409,000 Cuban families had immigrated to the U.S. This was made easier by the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act. This act gave permanent resident status to Cubans who had been in the United States for one year if they arrived after January 1, 1959.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

Everything changed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. This law was a result of the civil rights movement and part of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society programs. The law was not meant to bring more immigrants from Asia, the Middle East, Africa, or other developing parts of the world. Instead, by getting rid of the old quota system based on race, its creators expected immigrants to come from "traditional" countries like Italy, Greece, and Portugal. These countries had very small quotas under the 1924 law.

The 1965 Act replaced the quotas with new categories. These categories gave preference to people with family members already in the United States and those with job skills needed by the U.S. Department of Labor. After 1970, following an initial wave from European countries, immigrants from places like Korea, China, India, the Philippines, and Pakistan, as well as countries in Africa, became more common.

The 1980s: New Laws

In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) was passed. For the first time, this law created penalties for employers who hired illegal immigrants. IRCA was expected to give legal status to about 1,000,000 workers who were in the country illegally. In reality, it gave legal status to about 3,000,000 immigrants already in the United States. Most of these were from Mexico. The number of legal Mexican immigrant families grew significantly after this law.

The 1990s: More Immigration Changes

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) was passed in September 1996. This was a big immigration reform that focused on changing how undocumented immigrants were allowed in or removed. Its passing helped make U.S. immigration laws stronger. It also changed how immigration laws were enforced and tried to limit undocumented migration. These changes affected legal immigrants, those trying to enter the U.S., and those living in the U.S. without papers.

Asylum Rules Changed

IIRIRA created new challenges for refugees seeking asylum (protection) in the U.S. It made the rules for asylum stricter than those set in the Refugee Act of 1980. To stop people from falsely claiming asylum for economic reasons, IIRIRA set a "One Year Bar" for filing asylum applications. This meant you had to apply within one year of arriving. There were only limited exceptions to this rule. IIRIRA also made the asylum process harder by allowing refugees to be sent to other countries. It also stopped appeals for denied asylum applications, added higher processing fees, and let enforcement officers, not judges, decide on quick removals of refugees.

Dealing with Illegal Immigration

Law enforcement under IIRIRA was made stronger to limit unlawful immigration. The Act aimed to prevent illegal immigration by increasing the number of Border Patrol agents. It also allowed the Attorney General to get help from other federal agencies. Plans were also made to improve walls and other barriers along the U.S. border. IIRIRA also gave law enforcement powers to state and local officers through special agreements. Illegal entry into the U.S. became harder because federal and local law enforcement worked together. Penalties for illegal entry and crimes like smuggling people and document fraud also became tougher.

IIRIRA also dealt with unlawful migration already in the U.S. It did this by using better tracking systems. These systems could find people who were working illegally or overstaying their visas. It also created ID forms that were harder to fake. The Act also set up 3-year and 10-year bars for immigrants who had been in the U.S. illegally. This meant they could not re-enter the country for that time if they left.

The changes in law enforcement led to more arrests, detentions, and removals of immigrants. Under IIRIRA, many groups of immigrants were held in mandatory detention. This included those who had legal residence but could lose their status after committing serious crimes. Help and access to federal services for immigrants were also changed. IIRIRA repeated the 1996 Welfare Reform Act's system that divided people into citizens, legal immigrants, refugees, and illegal immigrants. This system decided who could get public benefits. Also, IIRIRA changed the rules for financial sponsors. Sponsors now had to meet an income requirement to sponsor an immigrant.

Immigration Data Since 1830

The tables below show where foreign-born people in the U.S. came from and how many people obtained legal permanent resident status over the years.

| Country/Year | 1830• | 1850 | 1880 | 1900 | 1930 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 2 | 148 | 717 | 1,180 | 1,310 | 953 | 812 | 843 | 745 | 678 |

| China | 104 | 1,391 | ||||||||

| Cuba | 439 | 608 | 737 | 952 | ||||||

| Dominican Republic | 692 | |||||||||

| El Salvador | 765 | |||||||||

| Germany | 8 | 584 | 1,967 | 2,663 | 1,609 | 990 | 833 | 849 | 712 | |

| India | 2,000 | |||||||||

| Ireland | 54 | 962 | 1,855 | 1,615 | 745 | 339 | ||||

| Italy | 484 | 1,790 | 1,257 | 1,009 | 832 | 581 | ||||

| Korea | 290 | 568 | 701 | |||||||

| Mexico | 11 | 13 | 641 | 576 | 760 | 2,199 | 4,298 | 7,841 | ||

| Philippines | 501 | 913 | 1,222 | |||||||

| United Kingdom | 27 | 379 | 918 | 1,168 | 1,403 | 833 | 686 | 669 | 640 | |

| Vietnam | 543 | 863 | ||||||||

| Total foreign born | 108* | 2,244 | 6,679 | 10,341 | 14,204 | 10,347 | 9,619 | 14,079 | 19,763 | 31,100 |

| % Foreign born | 0.8%* | 9.7% | 13.3% | 13.6% | 11.6% | 5.8% | 4.7% | 6.2% | 7.9% | 11.1% |

| Total population | 12,785 | 23,191 | 50,155 | 75,994 | 122,775 | 179,325 | 203,210 | 226,545 | 248,709 | 281,421 |

| 1830 | 1850 | 1880 | 1900 | 1930 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 |

| Year | Number | Year | Number | Year | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 8,385 | 1885 | 395,346 | 1950 | 249,187 |

| 1825 | 10,199 | 1890 | 455,302 | 1955 | 237,790 |

| 1830 | 23,322 | 1895 | 258,536 | 1960 | 265,398 |

| 1835 | 45,374 | 1900 | 448,572 | 1965 | 296,697 |

| 1840 | 84,066 | 1905 | 1,026,499 | 1970 | 373,326 |

| 1845 | 114,371 | 1910 | 1,041,570 | 1975 | 385,378 |

| 1850 | 369,980 | 1915 | 326,700 | 1980 | 524,295 |

| 1855 | 200,877 | 1920 | 430,001 | 1985 | 568,149 |

| 1860 | 153,640 | 1925 | 294,314 | 1990 | 1,535,872 |

| 1865 | 248,120 | 1930 | 241,700 | 1995 | 720,177 |

| 1870 | 387,203 | 1935 | 34,956 | 2000 | 841,002 |

| 1875 | 227,498 | 1940 | 70,756 | 2005 | 1,122,257 |

| 1880 | 457,257 | 1945 | 38,119 | 2010 | 1,042,625 |

Images for kids

-

European immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, New York City in 1915

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |