Union Stock Yards facts for kids

The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co., often called The Yards, was a huge area in Chicago where animals were processed for meat. It operated for over 100 years, starting in 1865. Railroad companies created this district by turning marshland into a central processing hub. By the 1890s, the powerful Vanderbilt family invested in the Union Stockyards.

The Yards were located in Chicago's South Side, in an area now called New City. They helped Chicago earn the nickname "hog butcher for the world." For many decades, Chicago was the center of the American meatpacking industry. The Yards, its workers, and its systems inspired books and social changes. They also became a place to study how industries worked.

The stockyards were key to the growth of some of the first international companies. These companies learned how to send products all over the world. They also developed new industrial ideas and influenced financial markets. The story of the Yards, from its rise to its closing, shows how transportation and technology changed in America. The stockyards are an important part of Chicago's history. They also played a big role in shaping the modern animal–industrial complex.

From the American Civil War until the 1920s, Chicago processed more meat than any other place globally. Construction began in June 1865, and the Yards opened on Christmas Day that same year. They closed on July 30, 1971, after many years of decline. The meatpacking industry had started to spread out to other locations.

The old Union Stock Yard Gate from 1877 is the only part of the original Yards left. It was made a Chicago Landmark in 1972 and a National Historic Landmark in 1981. Today, the area where the Yards once stood is mostly business and industrial parks.

Contents

History of Chicago's Stockyards

Before the big stockyards were built, local tavern owners would care for cattle herds waiting to be sold. As railroads grew, several smaller stockyards appeared around Chicago. In 1848, a stockyard called the Bulls Head Market opened. It was located at Madison Street and Ogden Avenue.

More small stockyards opened across the city in the following years. Between 1852 and 1865, five major railroads came to Chicago. These new stockyards were often built along the railroad lines. Some railroads even built their own stockyards. The Illinois Central Railroad and the Michigan Central Railroad together built the largest pens near Lake Michigan. In 1878, the New York Central Railroad bought a major share in the Michigan Central. This is how Cornelius Vanderbilt, who owned the New York Central, first got involved in Chicago's stockyard business.

Why the Stockyards Grew

Several things helped the Chicago stockyards grow and combine. Railroads expanded west between 1850 and 1870, making Chicago a major railroad hub. Also, the Mississippi River was blocked during the Civil War. This stopped all north-south river trade.

The United States government bought a lot of beef and pork to feed soldiers during the Civil War. As a result, the number of hogs arriving at Chicago's stockyards jumped from 392,000 in 1860 to 1,410,000 in 1864–1865. Beef arrivals also increased from 117,000 to 338,000 during the same time. Many butchers and small meatpacking businesses opened to handle this flood of animals. The goal was to process the livestock in Chicago, not send it to other cities. It became clear that a new, larger system was needed to keep up.

Building the Union Stock Yards

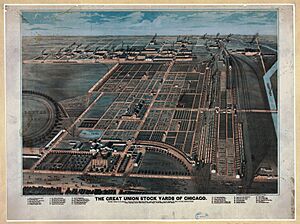

The Union Stock Yards were designed to bring all these operations together. They were built in 1864 on marshland south of the city. This area was south and west of the older stockyards. It was bordered by Halsted Street, South Racine Avenue, 39th Street, and 47th Street.

A group of nine railroad companies worked together to buy the 320-acre marshland for $100,000 in 1864. This is why it was called "Union" Stock Yards. The Yards were connected to the city's main rail lines by 15 miles of track. In 1864, the Union Stock Yards were just outside Chicago's city limits. But within five years, the area became part of the city.

Growth and Size of the Yards

Eventually, the 375-acre site had 2,300 separate pens for animals. It could hold 75,000 hogs, 21,000 cattle, and 22,000 sheep at one time. Hotels, restaurants, and offices for merchants also grew up around the stockyards.

Led by Timothy Blackstone, the first president of the Union Stock Yards and Transit Company, "The Yards" grew quickly. By 1870, two million animals were processed yearly. This number rose to nine million by 1890. Between 1865 and 1900, about 400 million livestock were processed there.

By the early 1900s, the stockyards employed 25,000 people. They produced 82 percent of the meat eaten in the country. In 1921, 40,000 people worked at the stockyards. Most worked for meatpacking companies with plants there. The Union Stock Yard & Transit Co. directly employed 2,000 people.

By 1900, the 475-acre stockyard had 50 miles of roads and 130 miles of track. At its largest, The Yards covered almost 1 square mile. It stretched from Halsted Street to Ashland Avenue and from 39th (now Pershing Road) to 47th Streets.

Environmental Impact

At one point, 500,000 gallons of Chicago River water were pumped into the stockyards daily. So much waste from the stockyards drained into the South Fork of the river that it was called Bubbly Creek. This was because of the gases from decomposition, and the creek still bubbles today. In 1900, Chicago permanently reversed the flow of the Chicago River. This was done to stop the stockyards' waste and other sewage from flowing into Lake Michigan and polluting the city's drinking water.

Transportation and Decline

From 1908 to 1957, a special Chicago 'L' train line served the meatpacking district. It had several stops and mainly carried thousands of workers and even tourists to the site every day. This line was built when the city made them remove surface tracks on 40th Street.

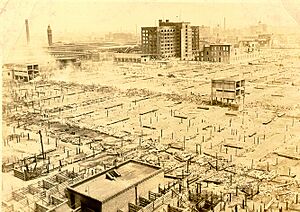

New ways of transportation and distribution led to less business. The Union Stock Yards closed in 1971. A company called National Wrecking cleared a 102-acre site. They removed 50 acres of animal pens and buildings. It took about eight months to prepare the land for a new industrial park.

How the Stockyards Changed Industry

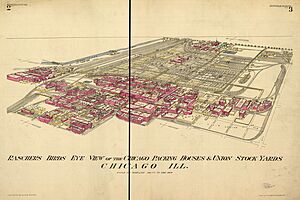

The large size of the stockyards, along with new technologies like rail transport and refrigeration, helped create some of America's first truly global companies. Entrepreneurs like Gustavus Franklin Swift and Philip Danforth Armour led these companies. Philip Armour built the first modern, large-scale meatpacking plant in Chicago in 1867. The Armour plant was located near the Union Stockyards.

This new plant used a modern "assembly line" method, but in reverse (a "dis-assembly line"). Animals moved along a line, and different workers performed specific tasks. This mechanized process, with its killing wheel and conveyors, later inspired the automobile assembly line that Henry Ford made famous in 1913. For a time, the Armour plant was known as the largest factory in the world.

Financial Innovations

The stockyard companies also played a big role in creating and growing Chicago's commodity exchanges and futures markets. These markets allowed sellers to guarantee a price for their products at a future date. This was very helpful for sellers who expected many animals to come to market at once, which could lower prices.

After Armour arrived in 1867, Gustav Swift's company came to Chicago in 1875. Swift also built a large, modern meatpacking plant. Other companies like Morris, Hammond, and Wilson also built plants near the Chicago stockyards.

Byproducts and Other Businesses

Many other businesses grew around the meatpacking plants. They made products from animal byproducts like leather, soap, fertilizer, and glue. There was even a "Hair Factory" that processed animal hair into useful items.

Next to the Union Stock Yards, the International Amphitheatre was built in the 1930s. It was originally for the annual International Live Stock Exposition, which started in 1900. This building later hosted many national conventions.

Historian William Cronon noted the positive impact of the Chicago packers. He said that ranchers and farmers had a reliable market for their animals and often got better prices. At the same time, Americans could buy more types of meat at lower prices. This "rigid system of economy" was seen as a very good thing.

Major Fires at the Yards

The first major fire started on December 22, 1910. It destroyed $400,000 worth of property and killed 21 firefighters, including Fire Marshal James J. Horan. Many fire companies fought the blaze for a day. In 2004, a memorial to all Chicago firefighters who died on duty was placed near the Union Stock Yards Gate.

A much larger fire happened on May 19, 1934. This fire burned almost 90 percent of the stockyards. It destroyed the Exchange Building and the Stock Yard Inn. The 1934 Stock Yards fire caused about $6 million in damages. One employee and 8,000 cattle died. The Yards were back in business the very next day.

Workers and Unions at the Stockyards

After the Union Stockyards opened in 1865, a community of workers grew up nearby. This area, west of the packing plants, was known as "Packingtown." At first, most residents were Irish and German.

By 1900, new immigrants from Poland, Slovakia, and Lithuania began working there. The jobs didn't need highly skilled workers, just strong ones. These jobs paid much more than anything in Eastern Europe, so new employees often brought their relatives over.

Historian Dominic A. Pacyga studied the Chicago Stockyards. He says they helped create a modern industrial culture with large companies and factory systems. He also showed how the Yards shaped the surrounding neighborhoods and helped many immigrant families, especially Polish workers, improve their lives.

Pacyga disagreed with the idea from Upton Sinclair's 1905 novel The Jungle that the stockyards were always filthy. He also didn't believe the stockyards dehumanized workers. Pacyga praised the new machines that made workers more productive and increased wages. These changes also made meat cheaper for American families. The stockyards' leaders generally did not like organized labor. To avoid strikes, companies offered welfare programs and pensions. Pacyga saw the rise of the stockyards as an amazing example of the modern age. Millions of people visited to see the meat processing. He explained that the stockyards declined in the 1950s as it became more profitable to slaughter animals closer to farms and use trucks instead of trains.

The Back of the Yards Community

Settlement in the area known as "Back of the Yards" began in the 1850s. It was first called the "Town of Lake." This name lasted until 1939. The local newspaper was even called the Town of Lake Journal.

In 1939, a community group called the "Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council" was founded. This is when the area west and south of the meatpacking plants started being called "Back of the Yards." Residents proudly adopted this name. The Town of Lake Journal officially changed its name to Back of the Yards Journal in 1939.

Early settlers in the "Town of Lake" included S. S. Crocker and John Caffrey. Crocker was even called the "Father of the Town of Lake." By February 1865, the area had fewer than 700 people. Before the Civil War, Cincinnati, Ohio, was the main meatpacking center. But after the war, the industry moved west to Chicago.

As early as 1827, Archibauld Clybourn was a butcher in Chicago. In 1848, the Bull's Head Stockyard opened on the West Side. However, this early stockyard mainly held and fed animals that were being sent to meatpacking plants further east.

Visitors to the community were often overwhelmed by the smell. This was caused by the packing plants and the 345-acre Chicago Union Stock Yards, which held 2,300 pens of livestock.

Decline and Modern Use of the Area

The stockyards thrived because of many railroads and refrigerated railroad cars. But their decline came from new transportation methods after World War II. It became cheaper to slaughter animals closer to where they were raised. This was thanks to better interstate trucking. This meant stockyards were no longer needed as much.

At first, the big meatpacking companies resisted these changes. But eventually, Swift and Armour closed their plants in the Yards in the 1950s.

In 1971, the area became The Stockyards Industrial Park. The neighborhood to the west and south is still called Back of the Yards. It continues to be home to many immigrant families.

The Historic Union Stock Yard Gate

A part of the Union Stock Yard Gate still stands today. It arches over Exchange Avenue, next to a memorial for firefighters. You can see it when driving along Halsted Street. The gate was made a Chicago Landmark in 1972 and a National Historic Landmark in 1981.

There is a plaque near the gate that tells the history of the Stock Yards. Another plaque on the gate itself remembers the "Fallen 21." These were the firefighters who died in the 1910 Chicago Union Stock Yards Fire.

This limestone gate is one of the few reminders of Chicago's history with livestock and meatpacking. The cow head decoration above the main arch is thought to represent "Sherman." This was a prize-winning bull named after John B. Sherman, one of the founders of the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company.

Impact on Animal Industry

The stockyards are seen as a major force that shaped the animal–industrial complex into its modern form. According to Kim Stallwood, Chicago and its stockyards from 1865 were a key moment in how humans treated animals. They helped create the animal–industrial complex. Other big changes came after World War II, like factory farms and industrial fishing.

Sociologist David Nibert noted that Chicago's slaughterhouses were powerful businesses in the early 1900s. They were known for the fast and efficient processing of huge numbers of animals.

See also

- Chicago Board of Trade

- Chicago Livestock World

- Chicago Mercantile Exchange

- List of union stockyards in the United States

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |