United Air Lines Flight 736 facts for kids

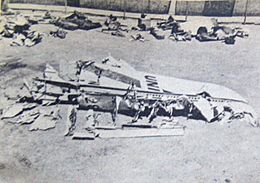

Some of the Douglas DC-7 wreckage collected for the crash investigation

|

|

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | April 21, 1958 08:30 PST (14:30 UTC) |

| Summary | Mid-air collision |

| Place | Enterprise, Nevada, United States 35°59′58″N 115°12′17″W / 35.9994°N 115.2046°W (DC7 crash site) |

| Total fatalities | 49 |

| Total survivors | 0 |

| First aircraft | |

A United Airlines Douglas DC-7 |

|

| Type | Douglas DC-7 |

| Airline/user | United Airlines |

| Registration | N6328C |

| Flew from | Los Angeles International Airport, California |

| 1st stopover | Stapleton International Airport, Denver, Colorado |

| 2nd stopover | Mid-Continent International Airport, Kansas City, Missouri |

| Last stopover | Washington National Airport, Washington, D.C. |

| Flying to | Idlewild Airport, New York City |

| Passengers | 42 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 47 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Second aircraft | |

North American F-100F fighter |

|

| Type | North American F-100F-5-NA Super Sabre |

| Airline/user | United States Air Force |

| Registration | 56-3755 |

| Flew from | Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada |

| Flying to | Nellis Air Force Base |

| Crew | 2 |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Survivors | 0 |

On April 21, 1958, a United Airlines passenger plane, Flight 736, crashed after hitting a U.S. Air Force fighter jet. This terrible accident happened over Clark County, Nevada, in clear weather. Both planes fell from the sky, killing all 49 people on board.

The crash of Flight 736 was one of several mid-air collisions in the 1950s. These accidents led to big changes in how planes are controlled in the sky. It also caused a major reorganization of the government groups that manage aviation.

Some passengers on the DC-7 were military staff and experts working on important Department of Defense projects. After the crash, new rules were made. These rules stopped groups of people working on the same critical projects from flying together on the same plane.

Investigators looked into the crash. They found that it was hard for the pilots to see each other's planes. The report didn't blame either flight crew directly. However, it criticized military and civilian aviation groups. These groups knew about the risks of collisions but didn't do enough to prevent them.

Lawsuits were filed after the crash. In one case, a judge said the Air Force pilots should have given way to the airliner. The judge also said the Air Force should have planned their training flights better. They needed to avoid busy areas and times when many civilian planes were flying.

Contents

What Happened Before the Collision?

United Airlines Flight 736's Journey

The plane for Flight 736 was a Douglas DC-7, a four-engine propeller plane. It joined the United Airlines fleet in early 1957. On April 21, 1958, it left Los Angeles International Airport at 7:37 a.m.

This flight was scheduled to go to New York City. It had planned stops in Denver, Kansas City, and Washington, D.C. The crew included Captain Duane Mason Ward, First Officer Arlin Edward Sommers, and Flight Engineer Charles E. Woods. There were 42 passengers, including military personnel and civilians.

After taking off, the DC-7 flew east towards Ontario, California. From there, it turned northeast towards Las Vegas. It joined a busy air route called "Victor 8" airway. This route was used by many planes, including large passenger airliners.

The United Airlines crew used the radio call sign "United 7-3-6." They were flying under instrument flight rules (IFR). This means they were guided by ground stations from the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA). Their planned cruising height was 21,000 feet.

The Air Force Jet's Training Flight

About eight minutes after the DC-7 left Los Angeles, a U.S. Air Force F-100F Super Sabre jet took off. It left Nellis Air Force Base near Las Vegas at 7:45 a.m. This was a training flight with two pilots.

Captain Thomas Norman Coryell, a flight instructor, was in the front seat. His trainee, First Lieutenant Jerald Duane Moran, was in the back. Moran was training to fly using only instruments. A special hood blocked his view outside the plane. This made him rely on his instruments, like flying in darkness or clouds.

The instructor's job was to watch for other planes and guide the trainee. The F-100F had dual controls, so the instructor could take over at any time. Part of the training involved a planned descent towards Nellis Air Force Base. This descent was called the "KRAM procedure." It involved flying down from 28,000 feet using a specific path.

At about 8:14 a.m., Flight 736 reported its position to CAA controllers. It was flying over a radio beacon east of Daggett, California. The crew expected to arrive over Las Vegas around 8:31 a.m.

At 8:28 a.m., the F-100F crew asked for permission to start their descent. They were cleared by the military controller at Nellis Air Force Base. As the jet flew south, the airliner was heading north-northeast at 21,000 feet. It was flying straight within its "Victor 8" airway.

The CAA controllers guiding the airliner did not know about the fighter jet. The Air Force controller guiding the jet did not know about the airliner.

The Collision in the Sky

At 8:30 a.m., with clear weather and excellent visibility, the two planes crashed. They collided about 9 miles southwest of Las Vegas. They hit almost head-on at 21,000 feet. Their combined speed was estimated to be very high, around 665 knots (about 765 miles per hour).

The Air Force jet, flying at 444 knots (about 511 mph), cut through the airliner's right wing with its own right wing. Both planes immediately went out of control. At the moment of impact, the F-100F was banking sharply to the left.

Witnesses saw the F-100F's wings "dip" just before the crash. Another witness said the fighter "swooped down." These descriptions suggest the Air Force crew tried to avoid the collision at the last second, but it was too late.

Moments after the crash, the United Airlines crew sent a distress call. It was heard at 8:30 a.m. plus 20 seconds. The message was: "United 736, Mayday, mid-air collision, over Las Vegas."

The damaged airliner, missing part of its right wing, spiraled down. It trailed black smoke and flames. The extreme forces caused by the spin ripped the engines from the plane. Seconds later, the rest of the aircraft began to break apart. The plane and its pieces fell into an empty desert area near Enterprise, Nevada. The nearly vertical fall and explosion made it impossible for anyone to survive.

The fighter jet also broke apart. Its right wing and tail were torn off. It left a trail of fragments as it fell steeply. One of the Air Force pilots called out a "Mayday" message, saying they were bailing out. The out-of-control jet crashed into a hilly desert area, about 5.4 miles southwest of the DC-7 crash site.

Witnesses thought they saw a parachute, hoping a pilot had ejected. However, it turned out to be a detached drag parachute, which is used to help the jet slow down after landing.

Investigations and Findings

The Federal Bureau of Investigation helped identify the victims. Among those who died were 13 civilian and military experts working on the American ballistic missile program. These experts were traveling to important meetings.

News reports from later anniversaries of the crash said the FBI also looked for sensitive national security papers. These papers were carried by the military contractors in special briefcases. The crash led to new rules. These rules prevented groups of technical people working on the same critical project from traveling together on the same plane.

Investigators from the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) studied the accident. Their report, released four months later, said the weather and the planes' condition were not factors. The main cause was the high speed at which the planes approached each other. Also, at high altitude, it was hard for pilots to see other planes.

The CAB investigation found that a metal frame in the F-100's cockpit blocked the instructor pilot's view. A support pillar on the DC-7's windshield might have blocked the United Airlines captain's view. However, the co-pilot's view in the airliner was not blocked.

The CAB report did not blame either flight crew. But it criticized the CAA and Nellis Air Force Base. They had failed to reduce known collision risks. Training exercises had been allowed in busy airways for over a year, even after many "near-misses" were reported by airline crews.

After the accident, the Air Force took steps to reduce collision risks in the Las Vegas area. The CAA also started a program to improve coordination between civilian and military aviation.

How the Crash Changed Aviation Safety

Calls for Better Air Traffic Control

The Flight 736 disaster happened during a time when many mid-air collisions were occurring. From 1956 to 1958, 245 military and civilian lives were lost in five major U.S. mid-air collisions. Each crash increased the pressure to improve how flights were controlled. The public, media, and airline pilots demanded changes. Pilots often spoke about military jets flying into civilian airways without warning.

An editorial in Aviation Week magazine called the loss of Flight 736 "another ghastly exclamation point." It said that modern aircraft were too fast and too numerous for the old air traffic control system. The magazine had warned about these problems years earlier.

The Flight 736 crash happened while the CAB was discussing expanding controlled airways. The news of the disaster spread quickly. Just 15 minutes after the hearing resumed, the CAB approved a new rule. This rule would ban aircraft without special clearance from entering certain airspace. All planes in this space would need to be equipped for instrument flight.

New Rules and Agencies

The CAB reported 159 mid-air collisions between 1947 and 1957. There were 971 near-misses in 1957 alone. Faster planes and more air traffic made it harder for pilots to see each other. The CAB said that "positive control" needed to be extended to higher altitudes and more routes. At the time, such control only existed in limited areas.

In April 1958, Aviation Week reported that the CAB admitted a full air traffic control plan would take "several years." They said a lack of people, money, and machines was holding back a nationwide control system.

After the April and May 1958 collisions, a congressional committee gave the CAB and Air Force a 60-day deadline. They had to create new control procedures. The committee also said that one civilian agency should control all airspace for all types of aircraft. Military flying should be controlled near airways, even in clear weather.

Four months after Flight 736, the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 became law. This act dissolved the CAA. It created the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA), later called the Federal Aviation Administration. The FAA was given complete authority over American airspace, including military flights. As air traffic control improved, airborne collisions became less frequent. The Las Vegas Review-Journal said the act "specifically referenced the crash of United 736" when creating the FAA.

Even with improved procedures, United Airlines had another mid-air collision in 1960. A United Douglas DC-8 jetliner and a TWA Super Constellation crashed over New York City. All 134 people on board died. In total, the three United Airlines collisions in 1956, 1958, and 1960 resulted in 311 deaths.

The F-100F jet involved in the Flight 736 crash was one of many F-100s lost in accidents. Almost 25 percent of these supersonic fighters were lost. 1958 was the worst year, with 47 F-100 pilots killed and 116 fighters destroyed. This was a loss rate of almost one jet every three days.

Crash Sites Today

The collision of Flight 736 was the deadliest aviation accident in the Las Vegas area's history, with 49 lives lost. However, the region has seen two other major airliner crashes.

In 1942, movie star Carole Lombard and 21 others died when TWA Flight 3 crashed into a mountainside. This was about 16 miles southwest of where Flight 736 crashed. In 1964, 29 people died when Bonanza Air Lines Flight 114 flew into a hilltop. This was about 5 miles southwest of the Flight 736 impact site, near where the F-100F crashed.

At the TWA Flight 3 and Bonanza Air Lines Flight 114 sites, some wreckage was left behind. This included parts of the planes and engines. However, the United Airlines DC-7 crash site was mostly cleared because it was flat desert.

In 1958, the DC-7 crash site was empty desert. But around 1999, buildings started to appear. Today, the spot where the DC-7 crashed is next to the Southern Highlands neighborhood. It is near the intersection of Decatur Boulevard and Cactus Avenue, surrounded by businesses.

For many years, a small engraved metal cross was the only sign of the crash. It was placed in 1999 by a victim's son. Efforts are now underway to encourage officials to build a permanent memorial. A video from April 2018 said the crash site is now under a parking lot. However, the metal cross still stands nearby on a small, undeveloped hill.

Images for kids

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |