Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Venezuelan naval blockade of 1902–1903 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

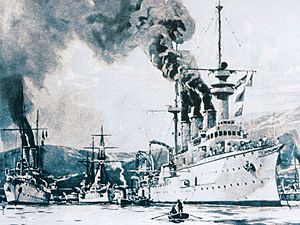

Engraving by Willy Stöwer depicting the blockade |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

The Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903 was a naval blockade (when ships stop other ships from entering or leaving a port) against Venezuela. Great Britain, Germany, and Italy carried out this blockade from December 1902 to February 1903.

It happened because Venezuelan President Cipriano Castro refused to pay back money owed to these countries. He also wouldn't pay for damages that European citizens suffered during recent civil wars in Venezuela.

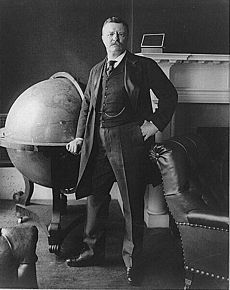

President Castro thought the American Monroe Doctrine would protect Venezuela. This doctrine said that the United States would stop European countries from taking over land in the Americas. However, at that time, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and his government believed the doctrine only applied to taking territory, not to military actions themselves.

Since the European powers promised they wouldn't take Venezuelan land, the U.S. stayed neutral. They allowed the blockade to happen without objection. Venezuela's small navy was quickly defeated. But Castro still refused to give in easily. Instead, he agreed to let an international group decide on some of the claims, which he had refused before. Germany initially disagreed with this idea.

Years later, President Roosevelt claimed he made the Germans back down. He said he sent his own large fleet and threatened war if the Germans landed troops. But there is no proof that he prepared for war or told his officials about such a threat.

Because Castro wouldn't give up, and with growing negative reactions in the British and American newspapers, the blockading nations agreed to a compromise. They kept the blockade going while they worked out the details. This led to an agreement on February 13, 1903. The blockade was lifted, and Venezuela agreed to use 30% of its customs money to pay off the debts.

Later, an international court decided that the countries that blockaded Venezuela should be paid first. The U.S. worried this would encourage Europe to interfere more in the future. This event helped create the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. This new idea said that the U.S. had the right to step in and help small countries in the Caribbean and Central America manage their money if they couldn't pay their international debts. This was to prevent European countries from stepping in instead.

Contents

Why the Blockade Happened

At the start of the 1900s, German traders were very important in Venezuela's trade and banking. However, they didn't have much power in Germany itself. It was German business owners and bankers, especially those building railways, who had connections.

Venezuela had many civil wars in the late 1800s. These wars caused problems for foreign businesses. For example, during the 1892 civil war, there was six months of chaos. In the 1898 civil war, people were forced to give loans, and houses and property were taken.

One important German company was Krupp's Great Venezuela Railway. This railway was worth a lot of money. Even though they changed their agreement in 1896, payments became irregular after 1897 and stopped completely in August 1901.

Also, Cipriano Castro, a military leader who became president in October 1899, stopped paying Venezuela's foreign debts. Britain also had similar complaints. Venezuela owed Britain most of its nearly $15 million debt from 1881, which it had failed to pay.

In July 1901, Germany kindly asked Venezuela to let an international court in The Hague help solve the problem. Between February and June 1902, the British representative in Venezuela sent Castro seventeen notes about Britain's concerns. Castro didn't reply to any of them.

Castro thought the United States Monroe Doctrine would make the U.S. stop any European military action. But President Theodore Roosevelt (who was president from 1901 to 1909) saw the doctrine as only stopping Europe from taking land. He didn't think it stopped other types of intervention. In July 1901, Roosevelt said that if a South American country misbehaved, a European country could "spank it." He repeated this idea to Congress in December 1901.

Getting Ready for Action

It's still debated how Britain and Germany decided to work together against Venezuela. In mid-1901, Germany's leader, Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow, decided to use military force. He talked with the German navy about a blockade.

There were delays because the German government disagreed on what kind of blockade to use. Also, Kaiser Wilhelm II, German Emperor wasn't sure about military action. Still, in late 1901, Germany sent two warships, SMS Vineta and Falke, to Venezuela. This was a show of strength to demand payments.

In January 1902, the Kaiser delayed any blockade because another civil war started in Venezuela. This war raised hopes for a new, more agreeable government. There were also rumors in the U.S. and England that Germany wanted Margarita Island as a naval base. But a German visit in 1900 found it wasn't suitable.

In late 1901, the British government worried they would look bad if they didn't protect their citizens' interests. They started talking to Germany about working together. At first, Germany said no. By early 1902, British and German bankers were pushing their governments to act.

Italy also wanted to be involved. Berlin first refused, but then agreed after Italy pointed out it could help Britain in Somalia. Italy quickly sent three warships toward Venezuela.

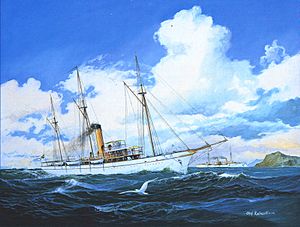

In June 1902, Castro seized a British ship, The Queen. He suspected it was helping rebels in the Venezuelan civil war. This, along with Castro ignoring British messages, made Britain decide to act, with or without Germany. By July 1902, Germany was ready to consider joint action. More problems had happened to German citizens and their property during the rebellion.

In mid-August, Britain and Germany agreed to a blockade later that year. In September, a rebel ship in Haiti hijacked a German ship. Germany sent a gunboat, SMS Panther, to Haiti. The German ship sank the rebel ship. The U.S. government said this was "illegal." But the U.S. State Department still supported the action. Similarly, Britain taking Patos Island near Venezuela didn't worry Washington.

On November 11, Kaiser Wilhelm and King Edward VII signed an agreement. It said that problems with Venezuela should be solved to both countries' satisfaction. This meant Venezuela couldn't make a deal with just one country. The agreement was partly because Germany feared Britain might back out. The British newspapers reacted very negatively to the deal. The Daily Mail said Britain was now "bound by a pledge to follow Germany in any wild enterprise."

Throughout 1902, the U.S. was told by Britain, Germany, and Italy that they planned to act. The U.S. said it wouldn't oppose any action as long as no land was taken. The British minister in Venezuela wanted the plans kept secret. He thought the U.S. minister would warn Castro, allowing him to hide Venezuela's gunboats.

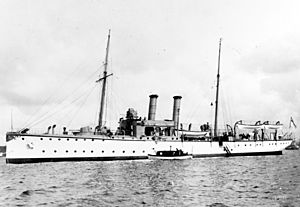

On December 7, 1902, London and Berlin gave ultimatums (final demands) to Venezuela. There was still disagreement about the type of blockade. Germany finally agreed to a war blockade. Venezuela didn't reply to the ultimatums. So, an unofficial naval blockade began on December 9. German warships like SMS Panther and SMS Vineta were involved. On December 11, Italy also gave an ultimatum, which Venezuela rejected. Venezuela said its laws were final and that foreign debt was not a matter for outside discussion.

The Blockade Begins

The German navy, with four ships, followed the British navy, which had eight ships. On December 11, 1902, the German ship Gazelle captured an old Venezuelan gunboat called Restaurador in the port of Guanta. The Germans put the ship into service as SMS Restaurador. It was returned to Venezuela in February 1903 after being repaired.

The British ships included HMS Alert and HMS Charybdis. An Italian navy group joined the blockade on December 16. The blockading forces captured four Venezuelan warships very quickly. Almost all of Venezuela's ships were captured within two days. The Germans sank two Venezuelan ships that were not seaworthy.

On land, Castro arrested over 200 British and German people living in Caracas. This made the allies send soldiers to get their citizens out. The U.S. Ambassador Herbert W. Bowen helped negotiate the release of all foreign citizens.

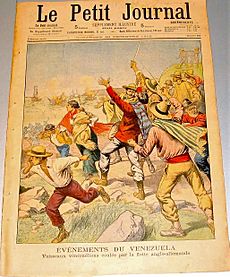

On December 13, a British merchant ship was boarded, and its crew briefly arrested. Britain demanded an apology. When they didn't get one, they bombed Venezuelan forts at Puerto Cabello. The German ship SMS Vineta helped. The same day, London and Berlin received a request from Castro, sent through Washington, to settle the dispute by arbitration. Neither country really wanted this.

Castro's offer only covered claims from the 1898 civil war, not other claims. Germany thought these claims should not be decided by arbitration. But Britain was more willing to agree. The threat of arbitration made London move to the next step. The official blockade was set to begin on December 20. Due to communication problems and delays, the British official blockade notice was published on December 20. But the German blockade of Puerto Cabello only started on December 22, and Maracaibo on December 24.

Meanwhile, American public opinion turned against the blockade. People talked about the nearby U.S. fleet, led by Admiral George Dewey, which was doing exercises in Puerto Rico. Neither the British government nor the British press thought the U.S. would actually intervene. The U.S. did send someone to check Venezuela's defenses. This confirmed that the U.S. Navy could stop a German invasion.

A British government report, which showed the "iron-clad" agreement, angered the British press. They thought joining British and German interests was dangerous and unnecessary just to collect debts. The poet Rudyard Kipling wrote a strong poem called "The Rowers" about it.

Britain unofficially told the United States on December 17 that it would accept arbitration. Germany also agreed on December 19. Castro's refusal to back down left few options. Taking Venezuelan territory, even temporarily, would cause problems with the Monroe Doctrine. Also, the negative reaction in the British and American newspapers made the intervention more costly, especially for Germany. Germany had followed Britain's lead throughout the operation. The British Ambassador in Berlin noted that Germany "accepted it at once because we had proposed it."

Roosevelt's Role: A Mystery

Fourteen years later, in 1916, President Roosevelt claimed that Germany agreed to arbitration because he threatened to attack their ships with Dewey's fleet. Historians have debated if this was true for a long time.

According to historian George Herring in 2011, "No evidence has ever been discovered of a presidential ultimatum." He says that Germany generally followed Britain's lead. Both nations accepted arbitration to get out of a difficult situation and stay on good terms with the United States.

However, historian Shaw Livermore says the U.S. Secretary of State's comments were "as close to a direct threat as it was possible to come in diplomatic parlance." Roosevelt also claimed Germany wanted to seize a Venezuelan harbor and set up a permanent military base. The German representative in Venezuela did have such plans. But historical records suggest the German Kaiser wasn't interested in this. The Kaiser only agreed after being sure Britain would lead the action.

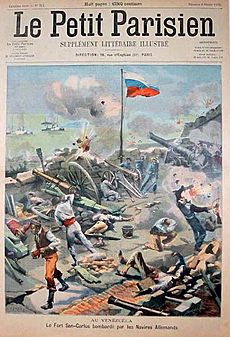

In January 1903, while negotiations continued, the German ship SMS Panther tried to enter the Maracaibo lagoon. This was a center for German trade. On January 17, it exchanged fire with Fort San Carlos. But it pulled back because the water was too shallow to get close enough to the fort. Venezuelans claimed this as a victory.

In response, the German commander sent Vineta, a ship with heavier weapons, to make an example. On January 21, Vineta bombed the fort. It set the fort on fire and destroyed it. Twenty-five civilians in the nearby town died. The British commander had not approved this action. He had been told not to do such things without asking London first. This message was not passed to the German commander.

This incident caused "considerable negative reaction in the United States against Germany." The Germans said the Venezuelans fired first. The British agreed but called the bombing "unfortunate and inopportune." The German Foreign Office said Panther tried to enter the lagoon to make sure the blockade of Maracaibo was effective. This would stop supplies from coming in from nearby Colombia. After this, Roosevelt told the German Ambassador that Admiral Dewey's fleet was ready to sail to Venezuela from Puerto Rico very quickly.

What Happened Next

After agreeing to arbitration in Washington, Britain, Germany, and Italy reached an agreement with Venezuela on February 13. This agreement was called the Washington Protocols. Venezuela was represented by the U.S. Ambassador to Caracas, Herbert W. Bowen.

Venezuela's debts were very large compared to its income. The government owed a lot of money in principal and interest. The agreement reduced the total claims by a large amount. It also created a payment plan that considered how much money Venezuela made. Venezuela agreed to use 30% of its customs income from its two main ports (La Guaira and Puerto Cabello) to pay the countries it owed money to. The blockade was finally lifted on February 19, 1903.

The Washington agreements set up groups to decide on claims against Venezuela. These groups worked well, and their decisions were accepted. The dispute was seen as settled.

However, the blockading nations argued that their claims should be paid first. Venezuela disagreed. On May 7, 1903, ten countries with complaints against Venezuela, including the United States, signed agreements to send the issue to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. On February 22, 1904, the Court decided that the blockading powers should indeed be paid first.

Washington disagreed with this decision. They feared it would encourage European countries to intervene in the future to get such an advantage. As a result, this crisis led to the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. In his 1904 message to Congress, Roosevelt said the United States had the right to step in and "stabilize" the money matters of small countries in the Caribbean and Central America if they couldn't pay their international debts. This was to prevent European intervention. The Venezuela crisis, and especially the court's decision, were key to developing this new idea.

See also

- Dutch–Venezuelan crisis of 1908

- Anglo-German naval arms race

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |