Weldy Walker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Weldy Walker |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

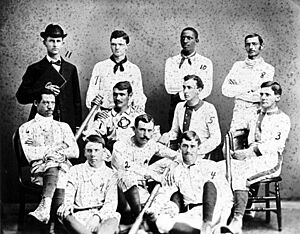

Weldy Walker cropped from portrait of the 1881 Oberlin College baseball team

|

|||

| Outfielder / Third baseman / Catcher | |||

| Born: July 27, 1860 Steubenville, Ohio, US |

|||

| Died: November 23, 1937 (aged 77) Steubenville, Ohio, US |

|||

|

|||

| debut | |||

| July 15, 1884, for the Toledo Blue Stockings | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| August 6, 1884, for the Toledo Blue Stockings | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Games played | 5 | ||

| Batting average | .222 | ||

| Hits | 4 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

|||

Weldy Wilberforce Walker (July 27, 1860 – November 23, 1937) was an American baseball player. In 1884, he became the third African American to play in Major League Baseball.

Walker played baseball at Oberlin College and the University of Michigan. In July 1884, he joined the Toledo Blue Stockings team. At that time, the Blue Stockings were part of Major League Baseball. His brother, Moses Fleetwood Walker, was the second African American to play in Major League Baseball. Fleetwood made his debut two months before Weldy.

In 1887, as racial segregation became common in professional baseball, Weldy joined the Pittsburgh Keystones. This team was part of the short-lived National Colored Base Ball League. In March 1888, Weldy wrote a powerful letter to The Sporting Life newspaper. This letter protested the unfair racial segregation in baseball.

After his baseball career, Walker managed restaurants and a hotel in eastern Ohio. In 1897, he helped lead the Negro Protective Party. This new political group formed in Ohio to protest a governor's failure to investigate a violent act against an African American. In the 1900s, Weldy and his brother Fleetwood became involved in the Back-to-Africa movement. They encouraged African Americans to move to Liberia. The brothers also started and edited The Equator, a newspaper focused on issues important to black communities.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Weldy Walker was born in 1860 in Steubenville, Ohio. This was an industrial city known for being more accepting of different races. Weldy's name combined the word "weldy" (meaning wealthy) with the last name of William Wilberforce. Wilberforce was a famous English leader who worked to end slavery.

Weldy's parents, Moses W. Walker and Caroline (O'Hara) Walker, moved to Steubenville. His father was a minister, a doctor, and a leader in Steubenville's African-American community. The Walker family was listed in the 1870 and 1880 US Census records. Weldy attended Steubenville's public high school, which allowed students of all races, in the 1870s.

College Baseball Career

While Weldy was still in high school, his older brother, Fleetwood Walker, went to Oberlin College. Oberlin was one of the first colleges in the United States to allow students of all races. In 1881, Weldy joined his brother at Oberlin College. He enrolled in the school's preparatory program.

In the spring of 1881, both Walker brothers played on Oberlin College's first official inter-collegiate baseball team. Weldy, who was a freshman, played right field. Fleetwood, a junior, was the catcher. Some records show that Weldy also played second base and was the team's second-best batter that season.

After the 1881 baseball season, Fleetwood transferred to the University of Michigan. He played as a catcher for the Michigan Wolverines baseball team in 1882. Fleetwood was the first African American to play on a varsity sports team at Michigan. He helped the Wolverines achieve a great record and win a championship.

Weldy first stayed at Oberlin, but then he also transferred to Michigan in the fall of 1882. He studied in the homeopathic medical school there. A newspaper noted that Weldy was a "magnificent fielder, safe batter, and phenomenal base runner." Before the 1883 season, Fleetwood left Michigan to play professional baseball.

During the 1883 season, Weldy became the second African American to play for the Michigan baseball team. He played third base for Michigan. Weldy also played catcher for Michigan during part of the 1884 season. He had a great game on June 14, 1884, helping Michigan win against Michigan Agricultural College. Both Walker brothers were accepted as students at the university, even though neither of them earned a degree.

Professional Baseball Career

Playing for the Toledo Blue Stockings

At the start of the 1884 baseball season, Weldy was still studying and playing baseball at Michigan. Meanwhile, his brother Fleetwood was playing for the Toledo Blue Stockings. This team was part of the American Association, which was considered a Major League Baseball league. On May 1, 1884, Fleetwood became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball.

As the 1884 season went on, the Toledo Blue Stockings had many injured players. They needed more players, so they asked Weldy to join his brother in Toledo. Weldy played his first game for the Blue Stockings on July 15, 1884. This made him the second African American to play Major League Baseball.

Weldy played in five games as an outfielder for the Blue Stockings between July 15 and August 6, 1884. He had four hits and a batting average of .222. A newspaper called The Sporting Life said that Weldy "played well." The Walker brothers were the last African Americans to play Major League Baseball for over 60 years. This changed when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

Baseball Segregation and Minor Leagues

Weldy believed that Chicago White Stockings player-manager Cap Anson was responsible for keeping African Americans out of the major leagues after 1884. During the 1884 season, Anson refused to play against Toledo unless the Walker brothers were removed from the game. In 1887, Anson again refused to play against a team that Fleetwood was on. Many historians agree with Weldy that Cap Anson played a big role in baseball becoming segregated.

After playing for the Blue Stockings, Weldy played for the Cleveland team in the Western League. In 1885, Weldy had a strong batting average of .375 for the Cleveland Forest Cities. In 1886, he played third base for the Excelsior Club in Cleveland.

Speaking Out Against Segregation

By early 1887, 13 African Americans were playing in the "white" minor leagues. Weldy started the season with the Akron Acorns. However, he only played in four games for them. During the 1887 season, racial segregation started to become official policy in some minor leagues.

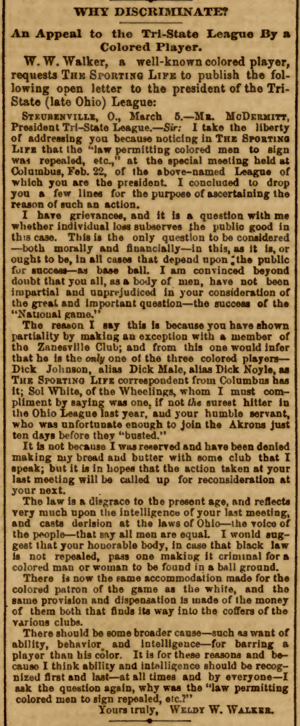

Weldy was very upset when he heard that the Tri-State League had decided to stop allowing black players. In March 1888, he wrote a letter to the league's president to protest this decision. A historian named Robert Peterson called Weldy's letter "perhaps the most passionate cry for justice ever voiced by a Negro athlete."

In his letter, Walker wrote: "The law is a disgrace to the present age... There should be some broader cause – such as lack of ability, behavior and intelligence – for barring a player, rather than his color. It is for these reasons... I ask the question again, 'Why was the law permitting colored men to sign repealed, etc.?'"

On March 14, 1888, Weldy's letter was published in The Sporting Life under the title "Why Discriminate?" His question was never truly answered. This showed how strong the Jim Crow system of segregation was becoming in America.

Playing for the Pittsburgh Keystones

In 1887, Weldy joined the Pittsburgh Keystones. This team was part of the new National Colored Base Ball League. Weldy had a .360 batting average in five games. Even though the National Colored Base Ball League quickly ended, the Keystones continued to play as an independent team.

Weldy became the team's manager in 1888. He led the Keystones to a great start, winning 9 out of their first 10 games. The Keystones team in 1888 also included Sol White, another important black baseball player. A newspaper noted that Weldy was "making quite a success of the Keystone Base Ball Club."

Civil Rights and Business Ventures

Fighting for Civil Rights in Court

In 1884, Weldy Walker was involved in a civil rights lawsuit. He and his friend, Hannibal Lyons, were not allowed into a roller-skating rink in Steubenville because they were black. A newspaper called The Cleveland Gazette reported on the situation. The rink owner told them, "You are colored and you can't skate."

Walker and Lyons sued the rink operator for racial discrimination. Some local newspapers suggested that Walker and Lyons were causing trouble. However, after a trial in January 1885, the judge ruled that the skating rink operator had violated their rights. The court awarded them each fifteen dollars in damages. But the court did not order the rink to allow African Americans to enter. This showed that while the law supported equality, it was hard to make it happen in real life.

The Negro Protective Party

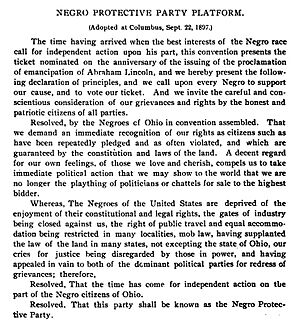

In the 1890s, Walker became active in politics. His activism grew stronger after a terrible event in June 1897. In Urbana, Ohio, a group of people violently took a black man named "Click" Mitchell from jail and killed him. Weldy and other African Americans in Ohio felt that the Republican Governor, Asa Bushnell, had not properly investigated this violent act.

Because of this, they left the Republican Party and formed the Negro Protective Party. Weldy was on the party's Executive Committee. He helped organize the party's meeting in Columbus, Ohio in September 1897. The party demanded "an immediate recognition of our rights as citizens." They also declared that they would no longer be "the plaything of politicians." The party also started publishing "The Negro Protector" newspaper.

When a former slave and Republican official, Nelson T. Gant, criticized Walker and the new party, Weldy responded with an open letter. He wrote that many "intelligent Negroes" would support the Negro Protective Party. He said they were free to leave the Republican Party without being called "betrayers."

The party faced challenges, including when the Ohio Secretary of State refused to print their symbol (an image of Abraham Lincoln) on the state ballot. The party took legal action. The party's candidate for governor received over 4,000 votes. The Cleveland Gazette newspaper believed that the governor's close victory was a direct result of his failure to act during the violent event in Urbana.

Business Interests

Even before he stopped playing baseball, Weldy started working in business. In October 1884, Weldy and a partner opened Delmonico Dining Rooms in Mingo Junction, Ohio. In 1897, Weldy and Joe Jetters opened a store selling oysters and fish in Steubenville.

In 1899, while his brother Fleetwood was in jail, Weldy began running the Union Hotel in downtown Steubenville. After Fleetwood was released, they ran the hotel together. In 1900, census records show Weldy living at the Union Hotel with Fleetwood and his family. Weldy was listed as a "porter" and Fleetwood as the operator of the boarding house. Later, Weldy was listed as the proprietor of the hotel.

The Back-to-Africa Movement

In the 1900s, the Walker brothers became active in the Back-to-Africa movement. In 1902, Fleetwood and Weldy started and edited a newspaper called The Equator, which focused on black issues. Six years later, they published a 47-page book called Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America.

In the book, the Walkers wrote that the only lasting solution to racial problems in the United States was for black people to move away from America. They believed that the "Negro race will be a menace and the source of discontent as long as it remains in large numbers in the United States." They also opened an office to help with resettlement to Africa. In 1908, Weldy listed his job as "General Agent" for their book and for Liberian emigration.

Later Years and Legacy

By 1910, Fleetwood had moved to Cadiz, Ohio, where he ran a theater. In April 1910, Weldy was still living at the boarding house in Steubenville, which was then run by his nephew, Thomas F. Walker. Weldy was listed as a "waiter."

In January 1920, Weldy was living with his nephew Thomas and Thomas's wife. Thomas was the hotel "keeper," and Weldy was listed as having no job. Weldy remained active in politics in his later years. He was friends with Harry Clay Smith, the editor of The Cleveland Gazette, a long-running African-American newspaper.

After Smith helped the Republican Party elect President Warren Harding in 1920, Weldy sent Smith a letter. He noted that the black vote helped Harding win. Weldy also wrote about the unfair treatment of black people in the Southern states. He asked, "When will 'Uncle Sam' allow the poor southern Negro 'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.'"

When Fleetwood died in 1924, Weldy and Thomas brought his remains back to Steubenville. Weldy never married. In November 1937, he passed away from pneumonia at his home in Steubenville.

|