Western Front tactics, 1917 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Western Front |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The First World War | |||||||

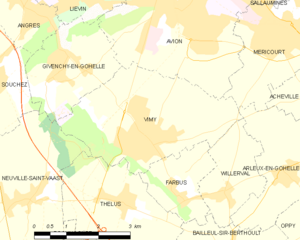

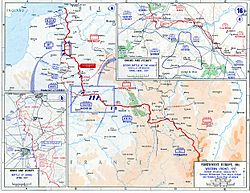

Map of the Western Front, 1917 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ferdinand Foch from early 1918 | Helmuth von Moltke the Younger → Erich von Falkenhayn → Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff → Hindenburg and Wilhelm Groener | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,947,000 | 5,603,000 | ||||||

In 1917, during the First World War, armies on the Western Front kept changing how they fought. This was because of new, powerful weapons and more automatic guns. Commanders also gave more freedom to smaller groups of soldiers. Special teams, equipment, and new methods became part of how infantry, artillery, and cavalry worked.

New technologies like tanks, railways, aircraft, and trucks became very important. Chemicals, concrete, and steel also played a bigger role. Photography and wireless communication helped armies. Advances in medicine saved many lives. The land, weather, population, and money also greatly affected how the war was fought. Armies faced a growing shortage of soldiers. They needed to replace those lost in 1916. Also, factories and farms needed workers. The French and German armies especially felt this shortage. They changed their fighting methods a lot that year. They wanted to win battles but also to keep their soldiers safe.

The French tried a big attack called the Nivelle Offensive in April. They used new methods from the Battle of Verdun in 1916. Their goal was to break through German lines and fight a war of movement. But the attack failed badly, and they spent the rest of the year recovering. The German army tried to avoid losing many soldiers. They pulled back to new, deeper, and spread-out defenses. This "defense in depth" aimed to stop the Allies' growing power, especially their artillery. It helped slow down the British and French on the battlefield.

The British (BEF) kept growing into a huge army. They became strong enough to challenge a major European power. They took on much of the fighting that the French and Russian armies had done since 1914. The German army had to find new ways to fight the British. The British were getting better at using their firepower and new technology. In 1917, the BEF also started to face soldier shortages. In December, at the Battle of Cambrai, they faced their biggest German attack since 1915. This was because German soldiers were moving from the Eastern Front to the Western Front.

How the Germans Prepared in Early 1917

New German Army Leaders

On August 29, 1916, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff took over the German army's top command (OHL). They replaced Erich von Falkenhayn, who had led the army since 1914. These new leaders, known as the Third OHL, had spent two years fighting on the Eastern Front. They had wanted more soldiers from Falkenhayn to win a big battle against Russia. They even worked against Falkenhayn when he refused.

Falkenhayn believed that a full victory against Russia was not possible. He thought the Western Front was the most important place to fight. Soon after taking over, Hindenburg and Ludendorff realized Falkenhayn was right. The Western Front was indeed the key, even with problems in the east from the Brusilov Offensive and Romania joining the war.

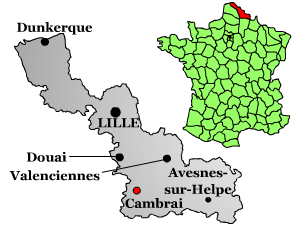

Meeting at Cambrai

On September 8, 1916, Hindenburg and Ludendorff met with army leaders at Cambrai. This was part of their visit to the Western Front. They were shocked by the trench warfare they saw. It was very different from the Eastern Front. The German army was in bad shape. The battles of Verdun and the Somme had cost many lives. On the Somme, over 120,000 German soldiers were lost in just over two months. The battle needed 29 divisions, and by September, one division had to be replaced every day.

General Hermann von Kuhl reported that Verdun was not much better. Recruit centers could only provide about half the needed replacements. From July to August, the German army fired huge amounts of artillery shells. But they received much less from Germany, causing a shortage of ammunition.

The 1st Army reported on August 28 that the enemy had more soldiers. But the biggest problem was the enemy's huge supply of ammunition. This allowed their artillery, helped by planes, to destroy German trenches. It also wore down their soldiers. German positions were so ruined that the front line was just shell-holes.

Germany knew that Britain had started conscription in January 1916. This meant Britain would have plenty of new soldiers, despite heavy losses. France's soldier situation was not as good. But by gathering men from rear areas and colonies, France could replace losses. This would last until new conscripts were ready in mid-1917.

Ludendorff privately told Kuhl that victory seemed impossible. Kuhl wrote in his diary that they agreed a big win was no longer possible. They could only hold on and look for the best chance for peace. They felt they had made too many serious mistakes that year.

On August 29, Hindenburg and Ludendorff reorganized the army groups on the Western Front. This helped move men and equipment. But it did not solve the lack of soldiers or the growing Allied advantage in weapons. New divisions were needed, and men had to be found to replace those lost in 1916. The Allies had more soldiers, but Hindenburg and Ludendorff had an idea. They listened to Lieutenant-Colonel Max Bauer from OHL HQ. He suggested a bigger effort from German industry. This would equip the army for the "battle of equipment" they faced in France. This battle would only get tougher in 1917.

Hindenburg Program

The new plan aimed to triple the output of artillery and machine guns. It also wanted to double the production of ammunition and trench mortars. Expanding the army and war material production meant more competition for workers. In early 1916, the German army had many recruits. Plans were even made to send older soldiers home. Falkenhayn had ordered 18 more divisions to be formed, making 175 divisions.

But the costly battles at Verdun and the Somme used up divisions quickly. They had to be replaced after only a few days on the front line. More divisions might ease the strain on the German army. Hindenburg and Ludendorff ordered 22 more divisions, aiming for 179 by early 1917.

Men for these new divisions came from reducing the size of existing divisions. They also came from rear-area units. But most had to come from the pool of replacements. This pool was shrinking due to losses in 1916. Even with new conscripts, replacing casualties would be harder with a larger army. By calling up the 1898 class early, the pool grew. But the larger army would become weaker over time.

Germany had started 1916 with plenty of artillery and ammunition. But four million rounds were fired in the first two weeks of Verdun. The Somme battle further reduced German ammunition. When infantry were forced from their positions, more "barrage fire" was needed. Before the war, Germany imported nitrates for explosives. Only the discovery of the Haber process (making nitrates from air) allowed Germany to continue the war. Developing this and building factories took time.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff wanted a huge increase in explosive output. But this demand for more production increased the need for skilled workers. Many workers were called back from the army or excused from conscription. This made the soldier shortage worse. Also, a lack of raw materials meant production goals were not met.

Despite these problems, by mid-1917, the German army had more field and heavy guns. Machine gun output allowed each division to have 54 heavy and 108 light machine guns. More machine-gun sharpshooter detachments were also created. But this increase was not enough to equip all the new divisions. British and French divisions still had more machine guns.

Defensive Battle Strategies

A new manual in December 1916 changed German defense policy. Instead of holding ground no matter what, they would defend positions good for artillery and communication. The idea was to make attackers "fight themselves to a standstill." Defenders would save their strength.

Defending soldiers would fight in zones. Front divisions would be in an outpost zone up to 3,000 yards deep. The main defense line would be on a reverse slope, hidden from enemy view. Behind this main line was a "battle zone," also hidden from the enemy. A "rear battle zone" further back would hold the reserve battalion of each regiment.

Building Field Fortifications

A guide on field fortifications was published in January 1917. By April, an outpost zone was built along the Western Front. Sentries could retreat to larger positions held by small attack groups. These groups would then counter-attack to retake the sentry posts. Defense in the battle zone was similar but with more soldiers.

The front trench system was the sentry line for the battle zone. Soldiers could move away from heavy enemy fire. Then they would counter-attack to regain the battle and outpost zones. These retreats would happen in small areas made impossible to hold by Allied artillery. This was a step towards "immediate counter-attack within the position." This decentralized fighting by small groups would surprise attackers. Resistance from automatic weapons, supported by artillery, would grow stronger the further the enemy advanced. A school opened in January 1917 to teach these new methods.

Allies had more ammunition and soldiers. So, attackers might still break through to the second line. This would leave German garrisons isolated in "resistance nests." These nests would still cause losses and confusion for the attackers. As attackers tried to capture these nests and dig in, German counter-attack divisions would move forward. They would launch an "immediate counter-attack from the depth." If this failed, the counter-attack divisions would prepare a careful attack later. This was if the lost ground was vital. Such methods needed many reserve divisions ready for battle. These reserves were created by reorganizing the army, bringing divisions from the Eastern Front, and shortening the Western Front. By spring 1917, the German army in the west had 40 reserve divisions.

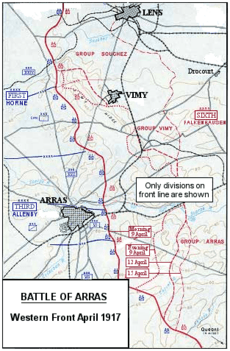

German 6th Army Defenses

General Ludwig von Falkenhausen, commander of the 6th Army, set up his infantry near Arras. He preferred a strong defense of the front line. This was supported by planned counter-attacks by "relief" divisions on the second or third day. Five relief divisions were placed 15 miles behind the front.

The new Hindenburg line ended at Telegraph Hill. From there, the original four-line system ran north. About three miles behind were the Wancourt–Feuchy lines. Further back, the new Wotanstellung was built. Allies did not fully map it until the battle began. Just before the battle, Falkenhausen thought parts of the front might be lost. But the five relief divisions could move forward to replace front divisions.

On April 6, General von Nagel, the 6th Army Chief of Staff, agreed that some front divisions might need relief on the first day. But any breakthroughs would be stopped by local counter-attacks from the front divisions. On April 7, Nagel saw the British attack as a small effort against Vimy Ridge. He thought it was a warm-up for a bigger attack later.

Building defenses for the new area defense was slowed by a lack of workers and the long winter. This affected concrete setting. The 6th Army leaders also did not want to thin out their front line. They feared this would make the British change their plans. British air reconnaissance was very good. It spotted new defenses and directed artillery fire on them. The 6th Army failed to move its artillery, which remained in easy-to-see lines. Defense work was split between maintaining the front, strengthening the third line, and building the new Wotanstellung further back.

German Corps Organization

Corps were separated from their divisions. They were given permanent areas to hold. These areas were named after their commanders, then by location from April 3, 1917. For example, the VIII Reserve Corps became Group Souchez. The I Bavarian Reserve Corps became Group Vimy. Divisions would move into an area and be controlled by that group. Then they would be replaced by fresh divisions.

German 18th Division Defenses

The 18th Division used the new defense system in the German 1st Army. It held part of the Hindenburg Position. It had an outpost zone along a ridge and a main defense line 600 yards behind. The battle zone was 2,000 yards deep and connected to the Hindenburg line.

Each of the three regiments held a sector. Two battalions were in the outpost and battle zones. One was in reserve, several miles back. (This setup was changed later in the year.) The two battalions were side by side. Three companies were in the outpost zone and front trenches. One company was in the battle zone. Four or five fortified areas, called "resistance nests," were built of concrete. They were designed for all-around defense. Each was held by one or two groups of 11 men and a non-commissioned officer with a machine gun.

Three and a half companies stayed in each front battalion area for mobile defense. During attacks, the reserve battalion would move forward to the Hindenburg line. These new arrangements doubled the area a unit held compared to July 1916 on the Somme.

British Attack Plans in Early 1917

Division Training for Attack

In December 1916, a new training manual, SS 135, was released. It was a big step in making the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) a strong, unified army. It helped the BEF fight better on the Western Front. The manual made rules for how armies, corps, and divisions should plan attacks. Armies would create the main plan and artillery rules. Each corps would assign tasks to divisions. Divisions would then pick targets and plan infantry attacks, with corps approval.

Artillery planning was controlled by corps. Divisions would give input using their local knowledge and air photos. The corps artillery commander would coordinate counter-battery fire. This meant firing at enemy guns. They also planned the howitzer bombardment for the start of the attack. Corps controlled the "creeping barrage," a moving wall of shellfire. But divisions could add extra batteries to the barrage and move them to other targets. SS 135 became the basis for the BEF's fighting methods for the rest of 1917.

Platoon Training for Attack

The training manual SS 143, from February 1917, changed how attacks were done. No longer would lines of infantry with a few specialists attack. The platoon was divided into a small headquarters and four sections:

- One section had two trained grenade-throwers and helpers.

- The second had a Lewis gunner and nine helpers carrying ammunition.

- The third section had a sniper, a scout, and nine riflemen.

- The fourth section had nine men with four rifle-grenade launchers.

The rifle and hand-grenade sections would move ahead of the Lewis-gun and rifle-grenade sections. They would move in two waves or in an "artillery formation." This formation covered an area 100 yards wide and 50 yards deep. The four sections were in a diamond shape: rifle section ahead, grenade sections to the sides, and the Lewis gun section behind. They would keep this formation until they met resistance. German defenders would be held down by fire from the Lewis-gun and rifle-grenade sections. Meanwhile, the riflemen and hand-grenade sections would move forward. They would try to go around the sides of the resistance and attack the defenders from behind.

These changes in equipment, organization, and formation were explained in SS 144, "The Normal Formation For the Attack," in February 1917. It suggested that leading troops should push to the final target if there were only one or two. But for more targets, if artillery fire could cover the whole advance, fresh platoons should move through the leading platoons to the next target. The new organization and equipment gave infantry platoons the ability to fire and move, even without strong artillery support. To make sure everyone used these new methods, Haig created a BEF Training Directorate in January 1917. It issued manuals and oversaw training. SS 143 and SS 144 gave British infantry ready-made tactics. These came from lessons learned on the Somme and from French army operations. They also matched the new equipment available from increased war production.

British Offensive Preparations

Planning for 1917 operations began in late 1916. The Third Army staff proposed their plans for the Battle of Arras on December 28. This started talks with GHQ. Sir Douglas Haig, the BEF Commander-in-Chief, reviewed the plan and made changes. This resulted in a more careful plan for the infantry. General Edmund Allenby, commanding the Third Army, suggested using mounted troops and infantry to push beyond the main force. Haig agreed, as the new spread-out German defenses gave more room for cavalry. The Third Army's requests for soldiers, aircraft, tanks, and gas were approved. Its corps were told to plan using SS 135, "Instructions for the Training of Divisions for Offensive Action." Behind the lines, improvements in roads and supply in 1916 led to new transport and road departments. This allowed army headquarters to focus on fighting.

Allenby and his artillery commander planned a 48-hour bombardment. This was based on the Somme experience, but shorter. After the bombardment, infantry would advance deep into German defenses. Then they would move sideways to surround areas where Germans held out. The 2,817 guns, 2,340 Livens projectors (gas projectors), and 60 tanks were placed based on the front length, wire to be cut, and new fuses. Guns and howitzers were assigned by their size and targets. Several barrages were planned, making the bombarded area deeper. Great importance was placed on counter-battery fire. This used sound to find German artillery positions.

Haig overruled a short bombardment. Allenby's artillery commander was replaced by Major-General R. St. C. Lecky, who wanted a longer bombardment. Allenby used a consultative style at first, encouraging corps commanders to get ideas from their subordinates. But later, he changed bombardment and counter-battery plans without discussion. However, he gave the Cavalry Corps commander freedom to act with other corps. During the battle, Allenby suggested setting aside artillery batteries to deal with German counter-attacks. These attacks became more effective as the Germans recovered. These batteries would be linked to the front by wireless. They would be aimed at likely German assembly areas.

Similar plans were made in the First Army further north. They were responsible for capturing Vimy Ridge. This would protect the Third Army's side. The commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne, kept a consultative style. On March 18, the XI Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Richard Haking, noted that two of his divisions held a four-division front. Horne explained how vital the attack on the ridge was. Conferences discussed German withdrawal, road use, and food for troops. They also stressed the importance of troops talking to planes and artillery.

XVII Corps Planning

XVII Corps issued a 56-page plan. It included lessons from the Somme. It stressed coordinated machine-gun fire, counter-battery artillery fire, and creeping barrages. It also covered infantry units leapfrogging, pauses on targets, and plans for German counter-attacks. Mortar and gas units were given to divisions. Tank operations remained a corps task. A Corps Signals Officer was appointed to coordinate artillery communications. This included detailed telephone line planning, telegraph, visual signals, pigeons, wireless, and liaison with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC).

Much of the corps planning covered artillery. It detailed guns moving forward behind infantry and their new positions. Artillery liaison officers were assigned to infantry units. Field guns and howitzers were saved to fight German counter-attacks. Artillery supporting a neighboring division would come under that division's command. For the first time, all artillery was part of one plan. Planning for the Battle of Arras showed that command relationships, especially within the artillery, became more integrated. Standardization was also clearer between armies, corps, and divisions. Analyzing lessons from the Somme and improving supply made the BEF less reliant on quick fixes. Discussion and disagreement were allowed. Staffs were more experienced. They could use a formula for planned attacks. But a faster pace of operations was not yet possible. This was because artillery relied on observed fire, which took time. Losing communication with troops once they advanced still left commanders unaware of events when decisions were most needed.

Division Level Planning

Intelligence Officers were added to divisions. They would work with headquarters as units moved forward. They would report on progress. This gave commanders more ways to react to events. Training for the attack began in the 56th (1/1st London) Division in late March. It mainly practiced for open warfare, with platoons organized by SS 143. Corps headquarters limited light signals to artillery: green for "open fire" and white for "increase range." It also set the strength of battalions and how many officers and men would be kept out of battle. The two attacking brigades returned to the line on April 1. This gave them plenty of time to study the ground before the April 9 attack.

On April 15, during the Battle of Arras, VI Corps sent a report to Allenby. It said that commanders from three divisions and the corps staff had decided to stop small, separate attacks. They wanted bigger, coordinated actions after a break to reorganize. Allenby agreed. On April 17, the 56th (1/1st London) Division commander objected to an operation planned for April 20. His troops were too tired. The division was pulled out instead. This happened because the VI and VII Corps commanders and General Horne, the First Army commander, also pushed for a delay.

VI Corps let divisions handle the barrage for the April 23 attack. This included changing barrage speed based on the ground. Third Army Artillery Instructions also mentioned using gas shells. A memo about low-flying German planes pointed to notes on firing at aircraft. Third Army Headquarters also let its corps give tank command to divisions for the Second Battle of the Scarpe. Decisions on local matters were increasingly left to division commanders. Corps kept control over general battle conduct.

British Methodical Attacks

After April 12, Haig decided that the advantage gained by the Third and First armies had run out. Further attacks would need to be more planned and careful. British intelligence thought nine German divisions had been replaced by nine fresh ones. On April 20, after the French Nivelle offensive began, Haig believed the German reserve had dropped. But 13 tired divisions were recovering, and 10 new ones were available for the Western Front. With French front reliefs, only about 11 fresh divisions would remain to fight more British operations. These continued until early May.

German Defensive Changes After Arras

The first days of the British Arras offensive were another German disaster. It was like the one at Verdun in December 1916. An analysis of that failure had quickly said that deep dugouts in the front line and no reserves for quick counter-attacks caused the defeat. At Arras, similar old defenses, with too many infantry, were destroyed by artillery and quickly overrun. Local reserves had little choice but to try to stop further British advances. They waited for relief divisions, which were too far away to counter-attack. Seven German divisions were defeated, losing many men and guns on April 9.

Given these two failures and the upcoming French offensive, the term "relief division" was dropped. It was replaced with "Eingreif division." This term meant "interlocking" or "dovetailing." It showed they were not just replacements but key reinforcements for defending battle zones. A more practical change was sending Loßberg from his post as Chief of Staff of the German 1st Army to the 6th Army. He replaced Nagel on April 11. Falkenhausen was fired on April 23 and replaced by General Otto von Below.

Loßberg quickly checked the 6th Army area. The British were attacking Bullecourt at the north end of the Hindenburg line. He confirmed the decision to pull back from the Wancourt salient and Vimy Ridge. He accepted that a rigid front defense was impossible with British observation from the ridge. North of the Scarpe, the front garrison could withdraw during British attacks. They would go to the rear edge of the battle zone. There, they would counter-attack with reserves. After dark, German infantry would redeploy in depth. South of the Scarpe, the loss of Monchy-le-Preux also gave the British observation over German positions.

Loßberg mapped a new line beyond British field artillery range. This would be the back of a new battle zone. At the front of the battle zone, he chose the old third line. This created a battle zone 2,500 yards deep. A rearward battle zone 3,000 yards deep backed onto the Wotan line, which was almost finished.

Despite Loßberg's doubts about flexible defense, he had to use it. With more artillery arriving, the first defense line was a heavy barrage on the British front line. This would happen at the start of a British attack. Then, direct and indirect machine-gun fire would hit British infantry as they advanced. This would be followed by infantry counter-attacks by local reserves and Eingreif divisions. Since the British might try to capture ground north of the Scarpe, Loßberg asked for a new Wotan II Stellung to be built.

In the battle zone, Loßberg ordered avoiding digging in. Instead, they would use "invisibility" (the emptiness of the battlefield). Machine guns were not to be in special fixed places. They would move among shell-holes and improvised spots. Specialist machine-gun units were moved back to the artillery protection line. They would act as rallying points for the front garrison. They would also provide fire to cover Eingreif units. Artillery was hidden in the same way. Guns were placed in folds of ground and moved often. This was to trick British air observers. The new setup was ready by April 13. The remaining front-line divisions were pulled out. Nine fresh divisions replaced them. Six more were brought in as new Eingreif divisions.

British Attack Plans in Mid-1917

British 5th Army Plans

Sir Douglas Haig chose General Hubert Gough, commander of the Fifth Army, to lead the attack from the Ypres salient. Gough held his first meeting on May 24. Four corps would be under the Fifth Army's command. Three corps would be in the Second Army. Early decisions could change. Planners were to use "Preparatory measures..." from February 1916 and SS 135. It was decided to have four divisions per corps: two for attack and two in reserve.

On May 31, Gough replied to a letter from Lieutenant-General Ivor Maxse. Maxse objected to dawn attacks, as a later start gave troops more rest. Maxse also wanted to go beyond the second objective to avoid stopping on a forward slope. Gough said he had to consider all corps commanders' wishes. But he agreed it was wise to gain as much ground as possible. He felt the Third Army had not done this at Arras.

In 1915, the BEF's biggest operation used one army, three corps, and nine divisions. In 1916, two armies, nine corps, and 47 divisions fought the Battle of the Somme. They did not have the decades of staff officer experience that European armies had. Instead of complex plans common in 1916, the XVIII Corps Instruction No.1 was only 23 pages long. It focused on principles and the commander's goal, as in "Field Service Regulations" 1909. Details became routine as more staff officers gained experience, allowing more delegation.

Great importance was placed on getting information back to headquarters. Troops were to be independent within the plan. This allowed a faster pace of operations. It freed attacking troops from waiting for orders. Corps commanders planned the attack within the army commander's framework. Planning in the Second Army followed the same system. In mid-June, Second Army corps were asked for their attack plans. When the II Corps boundary moved south in early July, the Second Army attack became mainly a decoy.

At the end of June, Major-General John Humphrey Davidson, Director of Operations at GHQ, wrote a memo to Haig. He said there was "ambiguity" about what a "step-by-step attack with limited objectives" meant. He suggested advances of no more than 1,500–3,000 yards. This would increase British artillery concentration and allow pauses for road repair and artillery movement. A rolling offensive would need fewer intense artillery fires. This would allow guns to move forward for the next stage. Gough stressed planning for chances to take undefended ground. He thought this was more likely in the first attack.

Haig met with Davidson, Gough, and Plumer on June 28. Plumer supported Gough's plan. Maxse, the XVIII Corps commander, wrote sarcastic comments in his copy of Davidson's memo, saying he was too pessimistic. Davidson's views were similar to Gough's. But Gough wanted extra arrangements to capture undefended ground through local action.

XIV Corps Plans

At a conference on June 6, Gough thought that if Germans were very demoralized, it might be possible to reach parts of the red line on the first day. Maxse and Rudolph Cavan (XIV Corps) felt their artillery range would limit their advance. They would need to move artillery forward for the next attack. Gough distinguished between attacking disorganized enemies (needing bold action) and organized forces (needing careful preparation, especially artillery). Maxse's wish for a later attack start was agreed, except by Lieutenant-General Herbert Watts. A memo was issued summarizing the conference. Gough stressed that front-line commanders needed to use their own initiative. They should advance into empty or lightly held ground beyond set targets, without waiting for orders. Relieving tired troops gave the enemy time. So, deliberate methods would be needed afterward. Judging when to do this was up to the army commander, based on reports from subordinates.

Communication from Fifth Army corps to their divisions showed lessons from Vimy and Messines. They valued aerial photography for counter-battery operations and raids. They also built scale models of the ground. Plans covered infantry, machine-gun positions, mortar plans, trench tramways, supply dumps, headquarters, signals, medical arrangements, and camouflage. The Corps was responsible for heavy weapons, roads, and communication. In XIV Corps, divisions were to work with 9 Squadron RFC for training. They were to practice infantry operations often. This would give commanders experience with unexpected events, which were more common in semi-open warfare.

XIV Corps held a conference for division commanders on June 14. Cavan stressed using new manuals (SS 135, SS 143, and Fifth Army document S.G. 671 1) for planning. They discussed how the Guards Division and 38th Division would meet the army commander's goal. The decision to patrol towards the red line was left to division commanders. This attack was not a breakthrough. The German Flandern I Stellung was 10,000–12,000 yards behind the front. It would not be attacked on the first day. But it was more ambitious than Plumer's plan. Notes were later sent to divisions from the next army conference on June 19.

At a conference on June 26, Gough's record (Fifth Army S.G.657 44) became the operation order for the July 31 attack. The final objective for the first day moved from the black to the green line. Infiltration towards the red line was planned. Responsibility for the attack would return to corps and Fifth Army headquarters when the green line was reached. In Gough's Instruction of June 27, he mentioned Davidson's concern about a ragged front line. He reminded corps commanders that a "clearly defined" line was needed for the next advance. Control of artillery would go to the corps. Gough issued another memo on June 30. It summarized the plan. It also mentioned the possibility of the attack moving to open warfare after 36 hours. He noted this might take several planned battles to achieve.

XVIII Corps issued Instruction No. 1 on June 30. It described a "rolling offensive." Each corps would have four divisions: two for attack and two in reserve. These reserves would move through the attacking divisions for the next attack. Separate units were assigned for patrolling once the green line was reached. Some cavalry were attached. Divisions were to build strongpoints and organize links with neighboring divisions. These groups received special training on model trenches. Ten days before the attack, divisions would send liaison officers to Corps Headquarters. Machine-gun units would be under corps control until the black line was reached. Then they would go to divisions. They would sweep the Steenbeek valley and cover the advance to the green line. Tanks were attached to divisions, with arrangements decided by the divisions. Some wireless tanks were available. Gas units remained under corps control. A model of the ground was built for all soldiers to inspect. Two maps per platoon would be issued. Plans for air-ground communication were very detailed. Aircraft recognition marks were given. Flares to be lit by infantry for contact planes were set. Recognition marks for battalion and brigade headquarters were laid down. Dropping stations were created to receive information from aircraft. Ground communication followed manual SS 148. Appendices covered engineer work on roads, rail, tramways, and water supply. Intelligence arrangements covered balloons, contact planes, forward observation officers, prisoners, returning wounded, neighboring units, and wireless eavesdropping. Corps Observers were attached to brigades. They would patrol forward once the black line was reached. They would observe the area up to the green line. They would judge German morale and see if they were preparing to counter-attack or retreat. This information would go to a divisional Advanced Report Centre.

Guards Division Plans

Training for the northern attack (July 31) began in early June. It focused on rifle skills and attacks on fortified positions. The Guards Division Signals Company trained 28 men from each brigade as relay runners. This was in addition to other communication methods. Major-General Fielding held a conference on June 10. They discussed the division's role in the XIV Corps plan for the attack east and north-east of Boesinghe. Four "bounds" (stages) were planned to different colored lines. Isolated German posts would be bypassed and dealt with by reserves. Depending on the German defense, patrols would take ground up to the red line. Captured German trench lines would be strengthened. Advanced posts would be set up beyond them. Teams were assigned to link with neighboring units and divisions. Six brigades of field artillery were available for the creeping barrage. The division's three machine-gun companies were reinforced by one from the 29th Division for the machine-gun barrage. Times for contact patrol aircraft to fly overhead and observe progress were given. The only light signals allowed were flares for contact aircraft and the rifle grenade SOS signal.

On June 12, the 2nd Guards Brigade began marching to the front line. On June 15, the relief of the 38th Division started. Preparations began to cross the Yser canal. It was 23 yards wide, empty, and had deep mud. A division conference on June 18 discussed the plans of the 2nd and 3rd Guards Brigades. They also talked about linking with the 38th Division on the right and the French 1st Division on the left. The 1st Guards Brigade, in divisional reserve, would use success to cross the Steenbeek and secure a bridgehead. If the Germans collapsed, it would advance east of Langemarck and Wijdendreft.

The 8th Division moved to Flanders a few days before the Battle of Messines Ridge (June 7–17). It joined XIV Corps in Second Army reserve. On June 11, the division came under II Corps. It began to relieve parts of the 33rd and 55th Divisions on the Menin Road at Hooge. Major-General William Heneker convinced Gough to cancel a preliminary operation. He included it in the main attack. On July 12, the Germans launched their first mustard gas attack on the division's rear areas and artillery lines. Two brigades would advance to the blue line with two battalions each. The other two would pass through to the black line. Four tanks were attached to each brigade. The 25th Brigade would then attack the green line, helped by 12 tanks. One battalion with tanks and cavalry would then be ready to advance to the red line. This depended on German resistance. The 25th Division would be in reserve, ready to attack beyond the red line.

After a night raid on July 11, the division was relieved by the 25th Division. It began intense training for trench-to-trench attacks. This was done on ground marked to look like German positions. A large model was built, and a large-scale map was made for officers and men to study. Officers and staff also checked the actual ground. The division's artillery was reinforced. It gained the 25th Divisional artillery, three army field brigades, and other heavy artillery groups. Six batteries of 2-inch, three of 6-inch, and four of 9.45-inch mortars were added. On July 23, the division returned to the front line. It began raiding to take prisoners and watch for local German withdrawals. Tunnelling companies prepared large underground chambers to shelter attacking infantry.

German Defensive Changes in June–July 1917

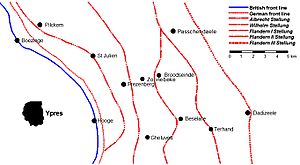

German Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht

Northern France and Flanders were held by Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht. By late July, it had 65 divisions. The defense of the Ypres Salient was the job of the German 4th Army. It was led by General Friedrich Bertram Sixt von Armin. The 4th Army's divisions were organized into groups based on existing corps. Group Lille ran from the southern army boundary to Warneton. Group Wytschaete continued north to Bellewaarde Lake. Group Ypres held the line to the Ypres–Staden railway. Group Dixmude held the ground north of the railway to Noordschoote. Group Nord held the coast with Marinekorps Flandern.

The 4th Army defended 25 miles of front. Group Dixmude had four front divisions and two Eingreif divisions. Group Ypres held 6 miles with three front divisions and two Eingreif divisions. Group Wytschaete held a similar length of front with three front divisions and three Eingreif divisions. The Eingreif divisions were placed behind the Menin and Passchendaele Ridges. Five miles further back were four more Eingreif divisions. Seven miles beyond them were two more in "Group of Northern Armies" reserve.

Behind the ground-holding divisions (Stellungsdivisionen) was a line of Eingreif divisions. The term "Relief Division" had been dropped before the French offensive in mid-April. This was to avoid confusion. "Eingreif" (meaning "interlock" or "intervene") was used instead. The 207th, 12th, and 119th Divisions supported Group Wytschaete. The 221st and 50th Reserve Divisions were in Group Ypres. The 2nd Guard Reserve Division supported Group Dixmude. The 79th Reserve Division and 3rd Reserve Division were at Roulers, in Army Group reserve. Group Ghent, with the 23rd and 9th Reserve Divisions, was around Ghent and Bruges. The 5th Bavarian Division was at Antwerp, in case of a British landing in the Netherlands.

The Germans feared a British attempt to use their victory at the Battle of Messines. They thought the British might advance to the Tower Hamlets spur. On June 9, Rupprecht suggested pulling back to the Flandern line east of Messines. Defense construction began but stopped after Loßberg became the new Chief of Staff of the 4th Army. Loßberg rejected the withdrawal. He ordered the front line east of the Oosttaverne line to be held firmly. The Flandernstellung (Flanders Position) along Passchendaele Ridge would become Flandern I Stellung. A new Flandern II Stellung would run west of Menin and north to Passchendaele. Construction of Flandern III Stellung east of Menin also began. From mid-1917, the area east of Ypres was defended by six German lines. These were the front line, Albrechtstellung, Wilhelmstellung, Flandern I Stellung, Flandern II Stellung, and Flandern III Stellung (under construction). Between these lines were the Belgian villages of Zonnebeke and Passchendaele.

Debate continued among German commanders. On June 25, Ludendorff suggested to Rupprecht that Group Ypres withdraw to the Wilhelm Stellung. Only outposts would remain in the Albrecht Stellung. On June 30, Kuhl suggested withdrawing to the Flandern I Stellung along Passchendaele Ridge. This would avoid a hasty retreat from Pilckem Ridge. It would also force the British into a time-consuming redeployment. Loßberg disagreed. He believed the British would launch a broad attack. He thought the ground east of the Oosttaverne line was easy to defend. He also believed the Menin Road Ridge could be held. Pilckem Ridge prevented the British from seeing the Steenbeek valley. German observation from Passchendaele Ridge allowed artillery to support infantry.

German 4th Army Defenses

The 4th Army's order for defensive battle was issued on June 27. The system of defense in depth began with a front system of three breastworks. These were about 200 yards apart. Each front battalion's four companies garrisoned them, with listening-posts in no-man's-land. About 2,000 yards behind these was the Albrechtstellung (second or artillery protective line). This was the rear boundary of the forward battle zone. Support battalion companies were split. 25% were "security garrisons" to hold strong-points. 75% were "shock troops" to counter-attack from the back of the forward battle zone. Half of these were in the pillboxes of the Albrechtstellung. This would help re-establish defense in depth once the enemy attack was stopped.

Divisional Sharpshooter machine-gun nests were spread out in front of the line. The Albrechtstellung also marked the front of the main battle zone. This was about 2,000 yards deep. It held most of the front divisions' field artillery. Behind it was the Wilhelmstellung (third line). In the Wilhelmstellung's pillboxes were reserve battalions of the front-line regiments. These were held back as divisional reserves.

From the Wilhelm Stellung to the Flandern I Stellung was a rearward battle zone. It contained support and reserve assembly areas for the Eingreif divisions. Failures at Verdun in December 1916 and Arras in April 1917 made these areas more important. The forward battle zone had been overrun in both offensives, and garrisons were lost. It was expected that the main defense would happen in the main battle zone. Reserve regiments and Eingreif divisions would fight attackers who had been slowed by the forward garrisons.

The leading regiment of the Eingreif division would advance into the front division's zone. Its other two regiments would move forward in close support. Eingreif divisions were placed 10,000–12,000 yards behind the front line. They would start their advance to assembly areas in the rearward battle zone. They would be ready to intervene in the main battle zone for an "instant-immediate counter-thrust." Loßberg rejected flexible defense tactics in Flanders. He thought there was little chance of breaks between British attacks. The British had so much artillery and ways to supply it. Much of this was built after the Messines attack in early June. Loßberg ordered the front line to be fought for at all costs. Immediate counter-attacks were to retake lost areas. Loßberg believed that a trench garrison that retreated under fire quickly became disorganized. It could not counter-attack, losing the sector and causing problems for troops on the sides.

Counter-attack was the main defense tactic. Local withdrawals would only disorganize troops coming to help. Front-line troops were not expected to stay in shelters, which were traps. They should leave them as soon as battle began. They would move forward and to the sides to avoid enemy fire and counter-attack. German infantry equipment had recently improved. Each regiment received 36 MG08/15 machine guns. The "Trupp" (eight men) was increased by a four-man MG08/15 crew to become a "Gruppe." The Trupp became a "Stoßtrupp" (shock troop). This extra firepower gave the German unit better ways to fire and move. Sixty percent of the front-line garrison were Stoßtruppen. Forty percent were Stoßgruppen, based in the forward battle zone. Eighty percent of the "Stoßkompanien" (shock companies) occupied the Albrecht Stellung. "Stoß-batallione" (shock battalions) were in divisional reserve. The Eingreif division (all shock formations) was based in the Fredericus Rex and Triarii positions. The core of all these defenses was a quick counter-attack.

British Attack Plans in Late 1917

British 2nd Army Plans

BEF GHQ staff quickly studied the results of the July 31 attack. On August 7, they sent questions to army headquarters. They wanted to know how to attack given German defense-in-depth. This involved strong points, pillboxes, and quick counter-attacks. Plumer replied on August 12. He stressed clearing captured ground. He also emphasized having local reserves for quick counter-attacks. More reserves were needed to crush organized counter-attacks. After a meeting with corps commanders on August 27, Plumer issued "Notes on Training and Preparation for Offensive Operations" on August 31. This expanded on his reply to GHQ. It described the need for deeper attacks and more local initiative. Unit commanders, down to infantry companies, should keep a reserve ready for counter-attacks. Communication was stressed. But standardization since 1916 allowed this to be simplified to a reference to SS 148.

Plumer issued a "Preliminary Operations Order" on September 1. It defined an attack area from Broodseinde southwards. Four corps with 14 divisions would be involved. Five of the 13 Fifth Army divisions extended the attack northwards. New infantry formations were introduced by both armies. This was to counter German pillbox defenses and the difficulty of keeping lines on ground full of flooded shell-craters. Waves of infantry were replaced by a thin line of skirmishers leading small columns. Maxse, the XVIII Corps commander, called this a "distinguishing feature" of the attack. Other features were the return to the rifle as the main infantry weapon. Stokes mortars were added to creeping barrages. "Draw net" barrages were used. Here, field guns started a barrage 1,500 yards behind the German front line. Then they crept towards it. These were fired several times before the attack. The organization set up before the Battle of Menin Road Ridge became the Second Army's standard method.

The plan relied on more medium and heavy artillery. This was brought from VIII Corps and by moving guns from the Third and 4th armies. The heavy artillery would destroy German strong points, pillboxes, and machine-gun nests. These were more numerous beyond the captured outpost zones. They would also engage in more counter-battery fire. 575 heavy and medium guns and 720 field guns were given to Plumer. This was one artillery piece for every 5 yards of front. This was more than double the proportion for the Battle of Pilckem Ridge. Ammunition for a seven-day bombardment was estimated at 3.5 million rounds. This created fire four times denser than for the July 31 attack. Heavy and medium howitzers would make two layers of the creeping barrage. Each layer was 200 yards deep, ahead of two field artillery belts. A machine-gun barrage was in the middle. Beyond the "creeper," four heavy artillery counter-battery groups covered a 7,000-yard front. They were ready to fire at German guns with gas and high-explosive shells.

British X Corps Plans

The three-week break in September came from Lieutenant-General Thomas Morland and Lieutenant-General William Birdwood. They were the X Corps and I Anzac Corps commanders. They spoke at the August 27 conference. The attacking corps made their plans within the Second Army framework. They used "General Principles on Which the Artillery Plan Will be Drawn" of August 29. This described the multi-layer creeping barrage and the use of fuse 106. This fuse avoided making more craters. Decisions on practice barrages and machine-gun barrages were left to corps commanders. The Second Army and both corps did visibility tests. They decided when the attack should start. They also discussed wireless and gun-carrying tanks with Plumer on September 15. X Corps issued its first "Instruction" on September 1. It gave times and boundaries to its divisions, with details to follow.

More details came from X Corps in a new "Instruction" on September 7. It set the green line as the final objective for the attack. The black line was for the next attack, expected about six days later. It reduced the barrage depth from 2,000 to 1,000 yards. It added a machine-gun barrage. This would be fired by attacking divisions and coordinated by the Corps Machine-Gun Officer and the Second Army artillery commander. Artillery details covered eight pages, and signaling another seven. A Corps Intelligence balloon was arranged to receive light signals. Messenger pigeons were given to corps observers. They reported to a Corps Advanced Intelligence Report Centre. This allowed information to be collected and shared quickly. Delegation forward was shown by the next "Instructions" on September 10. This gave a framework for the creeping barrage fired by divisional artillery. Details were left to the divisions, as was harassing fire on German positions. Double bombardment groups, used by X Corps at Messines, were linked with divisional headquarters. The X Corps report on the September 20 attack said success was due to artillery and machine-gun barrages. It also credited easy troop movement over rebuilt roads and better cooperation between infantry, artillery, and Royal Flying Corps.

Australian 1st Division Plans

On September 7, the 1st Australian Division commander announced the attack to his staff. The next day, the ground was studied. "Divisional Order 31" was issued on September 9. It gave the operation's goal and listed neighboring units. It detailed brigade placement and how the two attacking brigades would deploy. Each would have one battalion advancing to the first objective. Another would move through to the second. Two more would go to the final objective, 1,500 yards beyond the original front line. A map showed the red, blue, and green lines to be captured. A creeping barrage by the division's five field artillery brigades was described. Bombardments from corps and army artillery were also included. Special attention was given to clearing captured ground. Specific units were assigned to capture selected German strong points.

On September 11, "Divisional Order 32" detailed the march to the divisional assembly area near Ypres. On September 14, "Instruction No. 2" of Order 31 added artillery plan details. It also set routes for the approach march. The front line was checked again on September 15. Signallers began burying cables 6 feet deep. "Instruction No. 3" detailed strong points to be built on captured ground. These would hold a platoon each. Equipment and clothing were to follow SS 135, with an amendment that battalions on the final objective would carry more ammunition. Colored patches matching objective lines were to be worn on helmets. The 1st Australian Infantry Brigade would be held back. It would reinforce attacking brigades or defeat German counter-attacks. Compasses were given to officers. White tape would mark approach routes, starting points, and unit boundaries. This would help infantry keep direction. Troops attacking the first objective were told not to fix bayonets until the barrage began. This was to increase surprise.

"Instruction No. 4" included intelligence instructions. It covered questioning prisoners and sharing useful information. Men with armbands would search the battlefield for German documents. They would use maps of German headquarters, signal offices, and dugouts. Information would be sent to a divisional collecting point. "Instruction No. 5" focused on liaison. Officers were attached to brigades to report to the divisional commander. Brigades linked with other Australian brigades and neighboring divisions. Battalions linked in the same way. Artillery liaison officers were assigned down to infantry brigades. Battalion and company officers were told to stay close to artillery Forward Observation Officers. "Instruction no. 6" covered engineer and pioneer work for building strong points. An Engineer Field Company was attached to each brigade. The Pioneer Battalion was responsible for maintaining and extending communications. This included tramways, mule and duckboard tracks, and communication trenches. Two supply routes were defined. The next day, engineer officers were added to the liaison system within brigade headquarters.

Communication within the division was addressed by "Instruction No. 7" on September 16. It discussed telegraphs, telephones, and cable burying. Visual communication used six reporting stations. Wireless and power buzzers were also used. Motorcycle dispatch riders were linked to runners forward of brigade headquarters. Runners were no more than 50 yards apart. Messenger pigeons were given to brigades and artillery observers. Separate lines were laid for artillery. Aircraft liaison followed SS 148. Infantry battalions had panels to signal from the ground. "Instruction No. 8" covered medical arrangements. These ranged from Regimental Aid Posts to Casualty Clearing Stations. "Instruction No. 9" laid down machine-gun use in the attack. 72 machine guns would be part of the creeping barrage. The Divisional Machine-Gun Officer would stay close to brigade headquarters. He would be ready to act on SOS calls from infantry. "Instruction No. 10" summarized cooperation between infantry and artillery. It detailed artillery liaison down to battalions. A brigade of field artillery was added to the barrage. It was available to artillery liaison officers as needed. Divisional headquarters had two 6-inch howitzer batteries for the same purpose.

"Instruction No. 12" was issued on September 17. It covered equipment to be carried. A troop of Light Horse was attached to Major-General Harold Bridgwood Walker, the Divisional commander. They would carry orders. Restrictions were placed on telephone use in the front line to prevent German eavesdropping. Instructions 13–15, between September 18 and the attack, covered late changes. These included reserving telephone use for unit commanders. Two wireless tanks were provided for local use and as an emergency station for both Australian divisions.

To the right of the 1st Australian Division was the 23rd Division. It followed the same planning pattern. The warning order was issued on September 3. The divisional plan was issued on September 6. Appendices followed from September 9 to 15, with amendments on September 17. On September 8, X Corps instructed that division commanders take over their fronts on September 13. Brigade headquarters would take over on September 16. Intelligence gathering continued to update plans. When air photos showed ground around Dumbarton Lakes was muddier than expected, the plan changed. Infantry battalions sidestepped the marsh.

On September 11, the 23rd Division commander, Major-General James Melville Babington, told the X Corps commander, Lieutenant-General Thomas Morland, that he was leaving German counter-attack arrangements to his brigade commanders. But the area suggested by X Corps HQ was on a forward slope. He wanted to put the reserve behind the blue (second) line. Morland repeated his goal: ensure the counter-attack reserve was ready to act while German troops reorganized. But the means to do this were left to Babington's choice. The 23rd Division reserve brigade would handle any planned counter-attacks. A "Final Order" was issued on September 17 as a summary. It added information about the Bavarian Ersatz Division opposite and possible German counter-attack routes. It stressed that observation was needed over the Reutelbeek and Kronnebeek valleys when the final objective was secured. Situation reports were to be sent when brigades reached their objectives and every two hours afterward. Both divisions reached all their objectives on September 20. The 23rd Division "Comment on Operations" was published as a Second Army document. The pattern for later British attacks was set. Second Army orders and artillery instructions became standard.

German Defensive Changes in Late 1917

Changes After September 22

After the defeat at Menin Road Ridge on September 20, German defense tactics changed. In August, German front-line divisions had two regiments in the front line. The third regiment was in reserve. Front battalions were relieved much more often than expected. This was due to constant British bombardments, wet weather, and units getting mixed up. Reserve regiments could not intervene quickly. Front battalions were unsupported until Eingreif divisions arrived, hours after the British attack began. The deployment changed to put more troops in the front zone. By September 26, all three regiments of the front-line division were forward. Each held an area 1,000 yards wide and 3,000 yards deep. One battalion was in the front-line, the second in support, and the third in close reserve.

Battalions would move forward one after another. They would engage fresh enemy battalions that had moved through those that made the first attack. Eingreif divisions would launch an organized attack with artillery support later in the day. This would happen before the British could strengthen their new line. The change aimed to fix the problem of front division reserves being stopped by British artillery on September 20. This way, they could act before the Eingreif divisions arrived. On September 22, the 4th Army set new tactical rules. More artillery counter-bombardment would be used between British attacks. Half would be against British guns, half against infantry. More raids were ordered. This was to make the British hold their positions with more soldiers. This would give German artillery a denser target. Better artillery observation was needed in the battle zone. This would make German artillery fire more accurate when British troops advanced. Quicker counter-attacks were also to be made.

Changes After September 30

After costly defeats on September 20 and at Polygon Wood on September 26, German commanders made more changes. They altered their counter-attack tactics. These had been stopped by the British combination of limited attacks and much greater artillery power. German Eingreif divisions had engaged in "an advance to contact during mobile operations." This had achieved several costly defensive successes in August. German counter-attacks in September had been "assaults on reinforced field positions." This was due to short British infantry advances and focus on defeating hasty counter-attacks. The dry weather and clear skies in early September greatly increased British air observation and artillery accuracy. German counter-attacks were costly failures. They arrived too late to use the British infantry's disorganization. British tactics meant they quickly set up defense in depth on reverse slopes. This was protected by standing barrages. In dry, clear weather, specialist counter-attack reconnaissance aircraft watched German troop movements. Improved contact-patrol and ground-attack operations by the RFC also helped. German artillery that could fire, despite British counter-battery bombardment, became unsystematic and inaccurate. This was due to uncertainty about German infantry locations. Meanwhile, British infantry benefited from the opposite. On September 28, Albrecht von Thaer, a Staff Officer, wrote that the experience was "awful" and he did not know what to do.

Ludendorff later wrote that he often discussed the situation with Kuhl and Loßberg. They tried to find a solution to the overwhelming British attacks. Ludendorff ordered stronger front garrisons. All machine guns, including those of support and reserve battalions, were sent to the forward zone. They formed a line of four to eight guns every 250 yards. The "Stoß" regiment of each Eingreif division was placed behind each front division. This was in the artillery protective line behind the forward battle zone. This increased the ratio of Eingreif divisions to ground-holding divisions to 1:1. The Stoß regiment would be ready to counter-attack much sooner while the British were strengthening their positions. The rest of each Eingreif division would be held back for a methodical counter-attack on the next day or the one after. Between British attacks, Eingreif divisions would make more spoiling attacks.

A 4th Army order on September 30 noted that the German position in Flanders was limited. The nearby coast and Dutch border made local withdrawals impossible. The September 22 instructions were to be followed. More bombardment by field artillery would be used. At least half of the heavy artillery ammunition would be for observed fire on infantry positions. This included captured pillboxes, command posts, machine-gun nests, duckboard tracks, and field railways. Gas bombardment would increase on forward positions and artillery sites when the wind allowed. Every effort would be made to make the British reinforce their forward positions. This would give German artillery a target. They would do this by making spoiling attacks to retake pillboxes, improve defenses, and harass British infantry with patrols and diversionary bombardments. From September 26 to October 3, the Germans attacked and counter-attacked at least 24 times. BEF military intelligence predicted the German changes on October 1. They foresaw the big German counter-attack planned for October 4.

Changes After October 7–13

On October 7, the 4th Army stopped reinforcing the front defense zone. This was after the Battle of Broodseinde, the "black day" of October 4. Front-line regiments were spread out again. Reserve battalions moved back behind the artillery protective line. Eingreif divisions were organized to intervene as quickly as possible. This was despite the risk of being destroyed by British artillery. Counter-battery fire against British artillery would increase. This was to protect the Eingreif divisions as they advanced. Ludendorff insisted on an advanced zone, 500–1,000 yards deep. This would be held by a thin line of sentries with a few machine guns. The sentries would quickly retreat to the main line of resistance at the back of this advanced zone when attacked. Artillery would barrage the advanced zone. Support and reserve battalions of the ground-holding and Eingreif divisions would gain time. They would move up to the main line of resistance. The main defensive battle would be fought there if the artillery bombardment had not stopped the British infantry advance. An Eingreif division would be placed behind each front-line division. Instructions were to ensure it reached the British before they could strengthen their positions. If a quick counter-attack was not possible, there would be a delay to organize a methodical counter-attack after much artillery preparation.

The revised defense plan was announced on October 13. Rupprecht was reluctant to accept the changes. Artillery fire was to replace machine-gun defense of the forward zone as much as possible. Rupprecht believed that less counter-battery fire would give British artillery too much freedom. The thin line of sentries (one or two groups of 13 men and a light machine gun each) in company sectors proved too weak. The British easily attacked them and took prisoners. In late October, the sentry line was replaced by a normal outpost system. The German defense system evolved into two divisions holding a front 2,500 yards wide and 8,000 yards deep. This was half the area two divisions previously held. This need for more soldiers was caused by the weather, devastating British artillery fire, and the decline in German infantry numbers and quality. Hiding (the emptiness of the battlefield) was stressed. This was to protect divisions from British firepower. They avoided trench systems and spread out in crater fields. This method was only possible with quick unit rotations. Front-division battalions were relieved after two days, and divisions every six days.

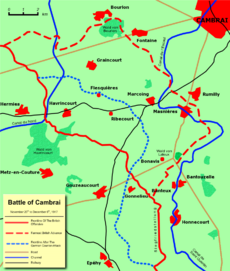

Surprise Attack at Cambrai, 1917

British 3rd Army Plans

The plan for the Battle of Cambrai started on August 23, 1917. Brigadier-General H. D. Du Pree of the IV Corps suggested a surprise attack with tanks near Flesquières. This would use the lack of German artillery there and good ground for tanks. The Third Army HQ (led by General Julian Byng) and Brigadier-General Henry Hugh Tudor, Royal Artillery Commander, greatly expanded the idea. It was then planned like earlier British attacks in 1917. These plans came from lessons learned on the Somme and French experience. Draft plans were sent to Corps. They included objectives and how to achieve surprise by not having a preliminary bombardment. Infantry would advance behind many tanks. They would reach the first two objectives (blue and brown lines) by leapfrogging. Cavalry would then advance to the red line and beyond. This was a new idea, made possible by surprise and a quick first advance. Details would be decided by the Corps. The third part of the plan needed cavalry to surround Cambrai. Infantry would follow. This would start in the south with III Corps, then move north with IV, VI, and XVII Corps. If it happened, the cavalry advance would be about 10 miles deep. This was two miles more than planned for the Arras offensive.

"Scheme GY" of October 25 was set up by Army conferences. Byng gave the objectives, leaving the methods to corps commanders. Third Army Headquarters then issued memos. They highlighted certain parts of the plan. "Third Army Instructions To Cavalry Corps" were sent by Byng to its commander on November 13. They covered linking with tanks and infantry. They described the cavalry's role: advance about 4.5 hours after the attack started. They would move through infantry at Masnières and Marcoing to surround Cambrai. On November 14, III Corps was told when to move its reserve, the 29th Division, forward. This was to capture canal crossings at Masnières and Marcoing. The RFC, Tank Corps, and Royal Artillery planned through Third Army HQ. This ensured new artillery techniques, tanks clearing wire, and air operations were coordinated.

Artillery planning for the attack saw the biggest change. It aimed to use the tactical power of "silent registration" (predicted fire). The artillery plan for the first part of the attack was decided by Third Army HQ. Corps were not allowed to make changes. This was until German resistance after the attack began needed Corps to take back tactical control. Silent registration and the need for secrecy led Third Army HQ to issue detailed instructions. These governed artillery use before the offensive. They also covered combining suppressive artillery fire with tank action. This would clear the way for infantry and cavalry.

British IV Corps Plans

Corps planning for the Cambrai operation followed the routine set in early 1917. IV Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Woolcombe) issued its draft plan on October 31. It gave the plan's idea, the three stages, and assigned troops. It also covered preparations and troop assembly. Administrative, intelligence, and signaling instructions were issued by corps staff. During planning, IV Corps issued more instructions for its divisions. This was especially for after the Hindenburg Support Trench system was captured. It stated that the Tank Corps would use all its tanks on the first day. Troops would move to the front just before the attack, not days before. This was to keep them fresh and prevent Germans from learning from prisoners. This decision gave infantry more time to train with tanks. This responsibility was given to infantry division commanders and the tank brigade attached to IV Corps. More instructions were issued from November 10–17. These covered concentration, secrecy, movements, order communication, codes, signals, later attack stages, and cavalry liaison.

The Tank Corps also followed this routine. It sent recommendations on unit distribution and tank training for approval by Third Army HQ. Proposals were based on "Notes" issued on October 4. These summarized Tank Corps experience since April. Amendments were issued on November 10. Third Army HQ issued two "Notes" on October 30. They covered tank-infantry training and operations. In "Tank and Infantry Operations Without Methodical Artillery Preparation" of October 30, each corps was told to keep instructions secret for surprise. Tank sections should attack specific areas. Objectives should be saved for a group of tanks each. An advanced tank should keep German heads down while the main body and infantry crossed German trenches. The main body of tanks should stay on the British side of the German line being attacked. Tanks would be assigned by the number of German positions. They would work in threes to cover 100–200 yards of front. Only a platoon of infantry should work with each tank. This was to avoid crowding when moving through wire lanes made by tanks. Infantry should move in single files. Further sections described care needed when tanks crossed wire. This was so following tanks would not pull up the wire. They also covered using and marking trenches filled by fascines (bundles of sticks) and tank-infantry cooperation principles.

In "Notes on Infantry and Tank Operations" October 30, Third Army HQ described tank characteristics and Tank Corps organization. It covered how to identify tanks, frontage per tank, formations, assembly, concealment, moving forward to attack, tank objectives, infantry cooperation, ammunition transport, wire and trench crossing, signaling, counter-battery work, staff liaison, and reporting. It stated that success depended on tanks' mechanical fitness, efficient assembly, clear objectives, prepared approaches, and thorough briefing of all tank and infantry officers. Third Army HQ gave operational control of tanks to III and IV Corps. These corps assigned tanks to their divisions for training. Each corps sent a staff liaison officer to the attached tank brigade headquarters.

The RFC continued to develop ground attack operations. It had a more systematic organization of duties and battlefield coverage. This came from lessons of the Third Battle of Ypres and work during the capture of Hill 70 in August. The smaller area at Cambrai and the RFC's growth meant more aircraft could be assigned to each task than in Flanders. The most notable difference in the air plan was in artillery cooperation. Air activity over Cambrai before the attack was limited to maintain secrecy. This left no time for artillery registration. Active German artillery positions would be observed once the battle began. Quick corrections would be given to artillery for counter-battery fire and for destructive fire against German infantry groups. Four fighter squadrons were saved for ground attacks against artillery, machine-gun nests, and troops. This followed a plan using lists of the most dangerous German artillery positions. Ground attack squadrons were given three groups of ground targets to patrol all day. A forward airfield was set up at Bapaume. This allowed aircraft to quickly resume patrols and attacks.

British 51st (Highland) Division Plans

The 51st (Highland) Division moved from the Ypres front in early October. It was surprised to be warned of another operation. It had already suffered 10,523 casualties in 1917. To surprise the Germans, the division stayed at Hermaville. A copy of the German defenses was built west of Arras. To mislead the Germans, the division did not occupy the front-line trenches before the attack. Observation parties visited the trenches wearing trousers instead of kilts. To gather the division in the battle area only 36–48 hours beforehand, the Commander Royal Engineers (CRE) with three engineer companies and an infantry battalion began preparing hidden shelters in the IV Corps area in early November. They provided camouflaged housing for 5,500 men at Metz and 4,000 men in Havrincourt Wood by November 19. Supply dumps, infantry and artillery tracks, dressing stations, and water points for 7,000 horses per hour were built. No increase in daytime lorry movement or work in forward areas was allowed.

Training was done on the replica, with tanks assigned to the division. The 1st Brigade of the Tank Corps, with 72 tanks, supplied a battalion to each of the two attacking infantry brigades. Twelve "Rovers" would move forward at the start. They would crush barbed wire and engage any machine-gun nests between German trench lines. About 150 yards behind the Rovers, a second wave of 36 "Fighting" tanks would deal with Germans in trenches up to the blue line. All remaining tanks would form a third wave. They would reinforce the first two waves for the attack on Flesquières Ridge. Three tanks were assigned to each platoon front of about 150 yards. Two tanks would attack Germans in the front trench. The center tank would advance to the trench beyond. The first two tanks would follow as soon as their infantry reached the first trench.

Due to many German communication trenches, sap heads, crater posts, and subsidiary trenches, the second wave tanks were given specific German positions. They had routes and positions in villages to deal with. They also attacked the main Hindenburg trenches. Infantry would follow 150–200 yards behind. They would attack trenches as soon as tanks engaged them and mark gaps in the wire. Each tank carried spare ammunition for the infantry. Training in the 51st and 62nd divisions differed from Tank Corps "Notes." Infantry kept a greater distance from tanks and moved in lines rather than single files. Rovers were used ahead of Fighting Tanks.

German Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht Defenses

Rupprecht and Kuhl were still worried about Flanders in November. They had lost Passchendaele village and more of Flandern II Stellung from November 6–10. The British offensive at Ypres might have ended. But no attack elsewhere was expected. Planning for 1918 operations had begun. On November 17, Rupprecht concluded that large attacks were unlikely. Small attacks on the 6th and 2nd armies were possible if the British had ended Flanders operations. The attack at Cambrai came "as a complete surprise." Ludendorff criticized the Army Group for being too focused on Flanders. The Army Group and OHL could only react to the British attack on November 20. They ordered reinforcements to rush to the 2nd Army. But Rupprecht pointed out that the rapid relief system in Flanders would break down if many divisions were moved. The rail network was overloaded, so quick reinforcement of Cambrai was not guaranteed. Ludendorff responded by taking more divisions from Army Group German Crown Prince in the central Western Front. The next day, Rupprecht ordered all truck-mounted anti-aircraft guns from the 4th and 6th armies to the 2nd Army. They would be used as anti-tank guns.

On November 27, Ludendorff, Rupprecht, and other staff met at the 2nd Army headquarters. Delays in transporting reinforcements and artillery ammunition were reported. Ludendorff agreed to postpone a counter-offensive until November 30. A more ambitious plan was made. It aimed to cut off British troops in the Bourlon salient and roll up the British line northward. This replaced the original plan to push the British back behind the Siegfried I Stellung. Rupprecht could offer two more divisions from Flanders. The main effort would be made by Groups Caudry and Busigny. They would attack west towards Metz village, capturing Flesquières and Havrincourt Wood from the south. Group Arras would attack southwards west of Bourlon Wood after the main attack began. Fresh divisions from Rupprecht and OHL Reserve would exploit success. Rupprecht wrote that regaining the Siegfried I Stellung positions was necessary. A smaller attack would be prepared by the 2nd Army north of St. Quentin if a great success was achieved.

German 2nd Army Defenses

The 2nd Army held the Western Front from south of Arras to the Oise. Many 2nd Army divisions had been exchanged for tired divisions from Flanders. On November 17, the 2nd Army thought it would be two more weeks before the 54th and 183rd Divisions were ready for battle. The 9th Reserve Division could only hold a quiet front. The 20th Landwehr Division was so damaged at Ypres that it would go to the Eastern Front. In Group Caudry, the loyalty of 350 troops from Alsace-Lorraine in the 107th Division was questioned. A lack of equipment meant the division could not be assessed. None of the divisions in Group Arras were considered battle-ready after their time in Flanders.

As soon as the British offensive began on November 20, reserves rushed to the area. An average of 160 trains per day arrived at Cambrai stations. Reinforcements and ammunition were not enough for an early counter-attack. November 30 was set for the counter-offensive after several delays requested by 2nd Army staff. A more ambitious counter-offensive was discussed on November 27. It required Group Arras to participate despite its divisions' tiredness. This was made worse by the delay in preparing the counter-offensive. Metz en Couture and the higher ground around Flesquières were 10 km behind the British front line. Doubts about the divisions in Group Arras, despite their need to participate, led to a compromise. An experimental deployment for the attack behind a smokescreen was used. The advance was delayed until after the attack by Groups Caudry and Busigny had taken effect.

German Group Formations