William Henry Bragg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Henry Bragg

|

|

|---|---|

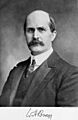

Portrait by the Nobel foundation (c. 1915)

|

|

| Born | 2 July 1862 Wigton, Cumberland, England, United Kingdom

|

| Died | 12 March 1942 (aged 79) London, England, UK

|

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Known for | X-ray diffraction X-ray spectroscopy Bragg's law Bragg peak Bragg–Gray cavity theory Bragg–Paul Pulsator |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physics (1915) Barnard Medal (1915) Matteucci Medal (1915) Rumford Medal (1916) Copley Medal (1930) Faraday Medal (1936) John J. Carty Award (1939) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University of Adelaide University of Leeds University College London Royal Institution |

| Academic advisors | J. J. Thomson |

| Notable students | W. L. Bragg Kathleen Lonsdale William Thomas Astbury John Desmond Bernal John Burton Cleland |

| Notes | |

|

He is the father of Lawrence Bragg. Father and son jointly won the Nobel Prize.

|

|

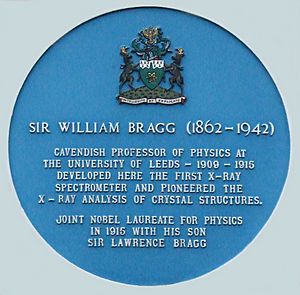

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist, chemist, and mathematician. He is famous for sharing the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915 with his son, Lawrence Bragg. They received the award for their work on understanding crystal structure using X-rays. This new field was called X-ray crystallography. The mineral Braggite is named after both him and his son. He was made a knight in 1920.

Contents

Biography of William Henry Bragg

Early Life and Education

William Henry Bragg was born in Westward, England, on July 2, 1862. His father was a merchant marine officer and farmer. When William was seven, his mother passed away. He was then raised by his uncle, also named William Bragg, in Market Harborough.

He went to the Grammar School in Market Harborough. Later, he attended King William's College on the Isle of Man. He then earned a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge. He finished his studies in 1884, excelling in mathematics.

Teaching in Australia

In 1885, at 23, Bragg became a professor at the University of Adelaide in Australia. He taught mathematics and experimental physics. When he started, he knew a lot about math but less about hands-on physics. He worked hard to improve the science teaching facilities. He even learned from instrument makers.

Bragg was a very popular teacher. He encouraged students to form a student union. He also let science teachers attend his lectures for free.

Discovering X-rays in Australia

Bragg became very interested in physics, especially after Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays. In 1896, Bragg showed local doctors how X-rays could reveal hidden structures. A chemist named Samuel Barbour provided the special glass tube needed for the X-rays.

Bragg used himself as a test subject. He had an X-ray taken of his hand. The image showed an old injury on one of his fingers. This injury was from using a turnip chopping machine on his father's farm.

Bragg also worked on early wireless telegraphy (radio) in Australia. He gave the first public demonstration of wireless telegraphy there in 1897. He even visited Guglielmo Marconi, who invented radio, in Europe.

A Turning Point in Research

A big change in Bragg's career happened in 1904. He gave a speech about how gases become ionized (gain an electric charge). This led to important research. Within three years, he became a member of the Royal Society in London. He also wrote his first book, Studies in Radioactivity.

In 1908, Bragg left Australia and returned to England. During his 23 years in Adelaide, the number of students at the university grew a lot. He played a key role in developing its excellent science department.

Research at the University of Leeds

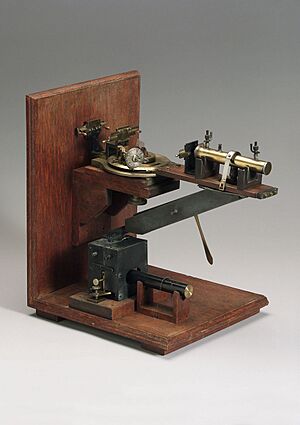

From 1909 to 1915, Bragg was a physics professor at the University of Leeds. He continued his successful work on X-rays. He invented the X-ray spectrometer. This device helps scientists study X-rays.

With his son, Lawrence Bragg, he started a new science called X-ray crystallography. This field uses X-ray diffraction to understand the structure of crystals.

Contributions During World War I

When World War I began in 1914, both of Bragg's sons joined the army. In 1915, he became a physics professor at University College London. He wanted to help with the war effort.

In July 1915, he joined the Board of Invention and Research for the Navy. Sadly, in September, his younger son Robert died in the Gallipoli campaign. In November, he and his elder son, William Lawrence, won the Nobel Prize.

The Navy needed help finding hidden German submarines. Scientists suggested listening for them underwater. Bragg became the scientific director at a research center in Scotland. He and his team developed better hydrophones, which are devices that listen for sounds underwater. These hydrophones helped the Navy find submarines.

Later, Bragg moved to the Admiralty, leading scientific research for the anti-submarine division. By the end of the war, British ships were using sonar (sound navigation and ranging) to detect objects underwater.

Post-War Work and Royal Institution

After the war, Bragg returned to University College London. He kept working on analyzing crystal structures.

From 1923, he worked at the Royal Institution as a professor of chemistry. He also directed the Davy Faraday Research Laboratory. Under his leadership, many important scientific papers were published from this lab. He gave several popular Christmas Lectures at the Royal Institution, explaining science to the public.

Leadership at the Royal Society

Bragg was elected president of the Royal Society in 1935. This is a very important scientific organization. He worked to make sure that science played a bigger role in preparing for future conflicts. He helped create a list of qualified scientists. He also pushed for a scientific advisory committee to help the government. He died in 1942.

Honours and Awards

William Henry Bragg and his son, Lawrence Bragg, jointly won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915. They were recognized for their work on analyzing crystal structures using X-rays.

Bragg became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1907. He was also its president from 1935 to 1940. He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1917. In 1920, he was knighted, becoming Sir William Henry Bragg. He also received the Order of Merit in 1931.

Other awards he received include:

- Matteucci Medal (1915)

- Rumford Medal (1916)

- Copley Medal (1930)

- Franklin Medal (1930)

- John J. Carty Award (1939)

Private Life

In 1889, in Adelaide, Bragg married Gwendoline Todd. She was a talented painter. Her father was Sir Charles Todd, a well-known astronomer and engineer. William and Gwendoline had three children: a daughter named Gwendolen and two sons, William Lawrence and Robert.

Bragg taught his son William at the University of Adelaide. Sadly, his son Robert was killed during the Gallipoli Campaign in World War I. Bragg's wife, Gwendoline, passed away in 1929.

Bragg enjoyed sports like tennis and golf. He helped bring the sport of lacrosse to South Australia. He was also involved in the Adelaide University Chess Association. William Henry Bragg died in 1942 in England. He was survived by his daughter Gwendolen and his son Lawrence.

Legacy and Impact

Many places and awards are named in honor of Sir William Henry Bragg. The lecture theatre at King William's College, where he studied, is named after him. One of the school "Houses" at Robert Smyth School in Market Harborough is also named "Bragg."

Since 1992, the Australian Institute of Physics has given out The Bragg Gold Medal. This award is for the best PhD thesis in physics by a student at an Australian university. The medal shows images of both Sir William Henry and his son Sir Lawrence Bragg.

The Bragg Building at Brunel University is named after him. The Sir William Henry Bragg Building at the University of Leeds opened in 2021. In 1962, the Bragg Laboratories were built at the University of Adelaide to celebrate 100 years since his birth.

The Australian Bragg Centre for Proton Therapy in Adelaide is named for both father and son. It provides special radiation therapy for cancer patients.

In 2013, a relative of Bragg, the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg, presented a BBC Radio 4 program about the father and son Nobel Prize winners.

See also

In Spanish: William Henry Bragg para niños

In Spanish: William Henry Bragg para niños

Images for kids