William Orton Williams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Orton Williams

|

|

|---|---|

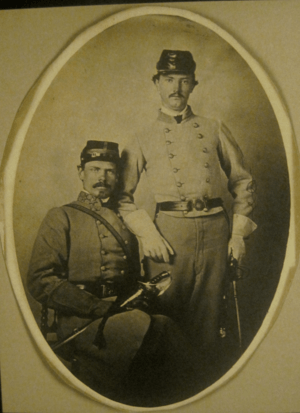

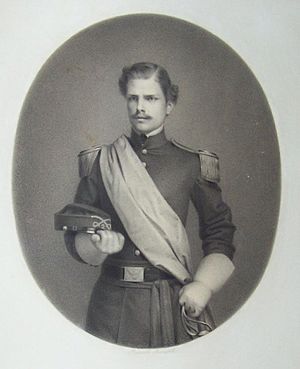

Second Lieutenant Williams, US Army 1861

|

|

| Other name(s) | Lawrence Williams Orton |

| Nickname(s) | Bunny |

| Born | July 7, 1839 Buffalo, New York |

| Died | June 9, 1863 (aged 23) Franklin, Tennessee |

| Buried |

Oak Hill Cemetery (Washington, D.C.)

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1861 (USA), 1861–1863 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

William Orton Williams (born July 7, 1839 – died June 9, 1863) was an officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He was first known as Orton Williams. Later, he changed his name to Lawrence Williams Orton. He became famous because he was caught behind Union lines wearing a U.S. Army uniform. He was then executed as a spy.

Contents

Early Life and Family Connections

Orton Williams was born in 1839. His father, Captain William G. Williams, was an officer in the Corps of Topographical Engineers. Sadly, his father died in 1846 from injuries during the Battle of Monterey. Orton's mother had passed away earlier. So, his older sister, Martha Custis Williams, raised him.

Orton was a cousin of Mary Anna Custis Lee. She was the wife of the famous Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Because of this family link, Orton spent a lot of time at Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial. He played there as a child. As a young man, he often visited Eleanor Agnes Lee, who was Robert E. Lee's third daughter.

Serving in the U.S. Army

In 1859, Williams worked for the United States Army Corps of Engineers. He helped survey the land in Minnesota. Later, he assisted with the Coast Survey. In 1861, Robert E. Lee suggested Williams for a military role. He was made a second lieutenant in the Second United States Cavalry. This was the same regiment Lee was in.

Williams was promoted to first lieutenant that same year. He served as an aide-de-camp (a personal assistant) to General Winfield Scott in Washington. When the Civil War began, he wanted to leave the U.S. Army. General Scott offered him a teaching job at West Point. This would let him stay in the army without fighting his family and friends. But Williams still wanted to leave. He was arrested because people thought he might have shared secret information with the Confederates. He was released after a few weeks. His brother, Lawrence, stayed in the U.S. Army.

Joining the Confederate Army

After leaving the U.S. Army, Williams joined the Confederate army. He was sent to the West. He served as an aide to General Leonidas Polk and fought in the Battle of Shiloh. Later, he was transferred to the artillery under General Braxton Bragg. During this time, his popularity decreased after some difficult events with soldiers.

He then changed his name to Lawrence Williams Orton. He said he did this because his brother was still in the Union army. In late 1862, while on leave in Virginia, Williams asked Eleanor Agnes Lee to marry him. She said no. He then married another woman shortly after.

His Final Days

On June 8, 1863, Colonel Orton and his cousin, Lieutenant Walter G. Peters, were arrested. They were behind Union lines in Franklin, Tennessee. They were dressed as Union Army officers. They also used false names and carried fake papers. These papers claimed they were U.S. Army inspectors.

When questioned, they told their real names to Colonel John P. Baird. He was the commander of the 85th Indiana Infantry Regiment. General William Rosecrans ordered Baird to have them tried by a court-martial right away. A court was quickly set up. It met during the night. At three in the morning on June 9, they were found guilty of being spies.

General Rosecrans did not accept pleas for mercy. He ordered their immediate execution. They were hanged about six hours after the verdict. It is not fully clear what Orton's mission was. Orton claimed they were on a secret mission for the Confederacy, heading to Canada and Europe.

Robert E. Lee was very upset by Orton's death. He agreed that the officers had broken the laws of war (rules of combat). But he believed they should have been shown mercy. Agnes Lee was also deeply saddened by Orton's death. It was a very hard time for her, coming only a year after her sister Annie had passed away.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |