Willie Brown (politician) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Willie Brown

|

|

|---|---|

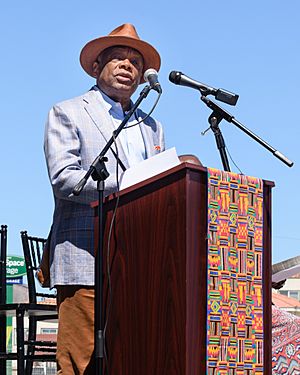

Brown in 2019

|

|

| 41st Mayor of San Francisco | |

| In office January 8, 1996 – January 8, 2004 |

|

| Preceded by | Frank Jordan |

| Succeeded by | Gavin Newsom |

| Minority Leader of the California Assembly | |

| In office June 5, 1995 – September 14, 1995 |

|

| Preceded by | Jim Brulte |

| Succeeded by | Richard Katz |

| 58th Speaker of the California State Assembly | |

| In office December 2, 1980 – June 5, 1995 |

|

| Preceded by | Leo McCarthy |

| Succeeded by | Doris Allen |

| Member of the California State Assembly | |

| In office December 7, 1992 – December 14, 1995 |

|

| Preceded by | Barbara Lee |

| Succeeded by | Carole Migden |

| Constituency | 13th district |

| In office December 2, 1974 – November 30, 1992 |

|

| Preceded by | John Miller |

| Succeeded by | Dean Andal |

| Constituency | 17th district |

| In office January 4, 1965 – November 30, 1974 |

|

| Preceded by | Edward M. Gaffney |

| Succeeded by | Leo T. McCarthy |

| Constituency | 18th district |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Willie Lewis Brown Jr.

March 20, 1934 Mineola, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Blanche Vitero

(m. 1958; separated 1981) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | San Francisco State University (BA) University of California, Hastings (JD) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | California Army National Guard |

| Years of service | 1955–1958 |

| Unit | 126th Medical Battalion |

Willie Lewis Brown Jr. (born March 20, 1934) is an American politician. He is a member of the Democratic Party. He served as mayor of San Francisco from 1996 to 2004. He was the first African American to hold this important office.

Willie Brown was born in Mineola, Texas. He moved to San Francisco in 1951 after high school. He studied at San Francisco State University and later became a lawyer. He was also involved in the civil rights movement, working for equal rights for all people.

In 1964, he was elected to the California Assembly. He became very well-known in San Francisco. He was seen as one of the most powerful state lawmakers in the country. He supported civil rights for all groups of people. From 1980 to 1995, he was the speaker of the California State Assembly. This is a very powerful leadership role.

After his time in the Assembly, Brown decided to run for mayor of San Francisco in 1995. During his time as mayor, San Francisco's economy grew quickly. He helped increase city projects like building new homes and improving public spaces. He was reelected in 1999. After leaving office in 2004, he retired from politics. The San Francisco Chronicle newspaper called him "one of San Francisco's most notable mayors."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Willie Brown was born on March 20, 1934, in Mineola, Texas. This was a small town with strict rules about racial segregation. He was the fourth of five children. His first job was shining shoes. He also worked as a janitor and a field hand. He learned to work hard from his grandmother.

He graduated from Mineola Colored High School. At 17, in August 1951, he moved to San Francisco to live with his uncle.

College and Law School

Brown was accepted into San Francisco State College even though he didn't quite meet the requirements. He worked very hard to catch up. He joined the Young Democrats and became active in his church and the San Francisco NAACP. He worked many jobs to pay for college, including doorman and shoe salesman.

He earned a bachelor's degree in political science from San Francisco State in 1955. After that, he went to Hastings College of the Law at the University of California. He worked as a janitor there to pay for his studies. He became friends with George Moscone, who later became a San Francisco mayor.

Starting His Law Career

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Brown opened his own law practice. He was one of the few African American lawyers in San Francisco at that time. He worked on criminal defense cases. He quickly became involved in the Civil Rights Movement. He led a protest against housing discrimination after a real estate office refused to work with him because of his race.

In 1962, Brown first ran for the California State Assembly. He lost that election but won his second attempt in 1964.

California State Assembly

In 1965, Willie Brown was one of four Black Americans in the California Assembly. He was reelected many times until 1995. In the 1960s, he became the leader of the Legislative Representation Committee. This powerful role helped him move up in the Assembly. He became the Democrats' Assembly whip in 1969.

In 1975, Brown helped pass a law that made homosexuality legal in California. This earned him strong support from San Francisco's gay community. He also voted against a law that banned same-sex marriage in 1977. These actions showed his support for the civil rights of gay and lesbian people.

Speaker of the Assembly

Brown became California's first Black American Speaker of the Assembly. He held this position from 1981 to 1995. In 1990, he helped end a long disagreement over the state budget. In 1994, he managed to keep his Speaker role even when his party lost control of the Assembly. He did this by making deals with some Republican lawmakers.

Because of his long time in the Assembly and his strong negotiation skills, Brown had a lot of control over California's laws. The New York Times called him one of the most powerful state lawmakers in the country. He even called himself the "Ayatollah of the Assembly."

Brown was very popular in San Francisco. However, he was less known in other parts of the state. To try and limit his power, a new law was passed in 1990. This law set term limits for state lawmakers. Brown tried to stop this law, but it was upheld by the courts. This law meant that no future Speaker could serve as long as Brown did.

Brown was known for always knowing what was happening in the state legislature. He helped get state money for San Francisco, especially for public health. He also held up the 1992 state budget for 63 days until the Governor added more money for public schools.

Mayor of San Francisco

In 1995, Willie Brown ran for mayor of San Francisco. He said the city needed a "resurrection" and that he would bring new leadership. He won the first round of voting. Then, he faced the current mayor, Frank Jordan, in a second election. Brown easily won and became mayor.

Brown's inauguration party was open to everyone, with 10,000 people attending. President Bill Clinton called to congratulate him. Brown gave his speech without notes and even led an orchestra. He arrived at the event in a horse-drawn carriage.

In 1996, most San Franciscans approved of Brown's work as mayor. He appeared on national TV shows. He wanted to expand the city's budget to hire more employees and start new programs. San Francisco's budget grew to $5.2 billion during his time, and 4,000 new city jobs were added. He also tried to create a plan for universal health care.

Brown worked long hours as mayor. He would often schedule many meetings in a day. He even opened City Hall on Saturdays to answer questions from the public. He later said that he helped bring back the city's spirit and pride.

Reelection as Mayor

In his 1999 reelection campaign, Brown faced former mayor Jordan and Clint Reilly. Some people criticized Brown for spending a lot of money without solving major city problems. They also said there was too much favoritism in City Hall. Tom Ammiano also ran against Brown.

Brown won reelection by a large margin. Most major businesses and developers supported him. President Clinton even recorded a phone message to help Brown's campaign. Brown's campaign spent much more money than his opponent's.

City Services and Public Safety

Brown changed San Francisco's policy on feeding homeless people, making it no longer punishable. However, the city continued to enforce rules about homeless people's behavior in public. In 1998, Brown supported efforts to move homeless people from Golden Gate Park. He also supported police actions against public drunkenness or sleeping on sidewalks. His administration spent a lot of money on new shelters and drug treatment programs.

In 1996, Brown approved a law that required city contractors to offer benefits to domestic partners of their employees.

Transportation Improvements

One of Brown's main promises was to fix the city's bus system, Muni, within 100 days. He supported a program that paid former gang members to patrol Muni buses, which he said helped reduce crime. He increased Muni's budget by millions of dollars. He later admitted that he had promised too much with his 100-Day Plan.

Brown also helped settle a strike by BART workers in 1997. He supported replacing the old Transbay Terminal with a new one, which became the Salesforce Transit Center.

Critical Mass Cycling Events

Since 1992, cyclists in San Francisco's monthly Critical Mass rides would block traffic at intersections. In 1997, Brown approved a plan to crack down on these rides. He called them "a terrible demonstration of intolerance." After some arrests, Brown suggested taking away their bicycles and putting riders in jail. On July 25, 1997, 115 riders were arrested.

However, by 2002, Brown's view on Critical Mass had changed. For their 10th anniversary, the city closed four blocks to cars for a "Car-Free Day Street Fair." Brown said, "A new tradition has been born in our city."

City Planning and Development

As mayor, Brown was sometimes criticized for having too much power and favoring certain businesses. However, his supporters point to many successful development projects. These included restoring City Hall and historic waterfront buildings. He also started the large Mission Bay development project.

Under Brown, City Hall was repaired after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. He made sure the dome was covered with real gold. The Embarcadero area was redeveloped. The historic Ferry Building was restored. New museums like the Asian Art Museum and the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum were built. The Moscone Convention Center and San Francisco International Airport's new international terminal were also expanded.

Brown worked with the San Francisco Giants baseball team to build a new stadium in the China Basin. Voters approved the stadium in June 1997, and it opened in 2000.

After Being Mayor

After leaving the mayor's office, Brown thought about running for the California State Senate but decided not to. From 2006, he hosted a morning radio show and a weekly podcast. He also started The Willie L. Brown Jr. Institute on Politics & Public Service at San Francisco State University. This organization helps students learn about careers in local government. He gave his collection of artifacts and papers from his 40 years in public office to the institute's library.

In 2008, Brown published his autobiography, Basic Brown: My Life and Our Times. In July 2008, he started writing a column for the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper.

In September 2013, the western part of the Bay Bridge was officially named after Willie Brown. In 2015, he joined the board of directors for a company called Global Blood Therapeutics. Brown has continued to help raise money and advise other politicians.

Transportation Company Work

In late 2012, Brown became a lawyer for Wingz, a ride-sharing service. He represented the company before the California Public Utilities Commission. This commission was creating new rules to allow ride-sharing services to operate legally in California.

In the Media

As mayor, Brown was often shown in cartoons and articles as a stylish leader. He enjoyed this attention. His unique style made him very well-known.

Brown was so famous for his political style that he even appeared in movies. He played a politician in The Godfather Part III (1990). He also played himself as the Mayor of San Francisco in two Disney films, George of the Jungle (1997) and The Princess Diaries (2001). He also appeared as the mayor in the 2003 film Hulk. He was also on an episode of the TV show Nash Bridges.

In 1998, Brown contacted the Japanese cooking show Iron Chef. He suggested a San Francisco chef to compete on the show and appeared on the telecast himself.

Personal Life

Family

In September 1958, Willie Brown married Blanche Vitero. They had three children together. They separated in 1981 but are not divorced. Brown also has another daughter, Sydney Brown, with Carolyn Carpeneti. He has four grandchildren and one great-grandson.

Eyesight Condition

While he was Speaker of the Assembly, Brown was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP). This is a disease that slowly damages eyesight and can lead to blindness. Brown's two sisters also have RP. He said, "Having RP is a challenge. ... Reading is also very difficult so I use larger print notes and memos." He learned to listen more carefully and memorize a lot of information.

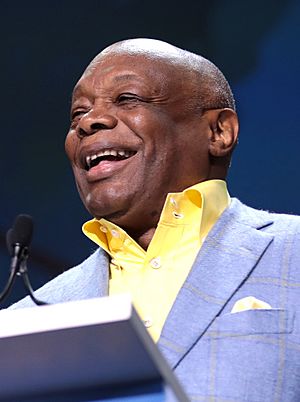

Personal Style

Brown has always used his personal style to express himself. This helped him become very visible and was even a political advantage. He was known for wearing fancy British and Italian suits, driving sports cars, and collecting stylish hats. Esquire magazine once called him "The Best Dressed Man in San Francisco."

In his 2008 book, Basic Brown, he wrote about his love for expensive suits and his search for the perfect chocolate Corvette. He even suggested that men should have different navy blazers for each season. He said, "You really shouldn't try to get through a public day wearing just one thing. ... Sometimes, I change clothes four times a day."

Awards and Honors

- 1990: Adam Clayton Powell Award

- 1996: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

- 2014: Legacy Award of the National Newspaper Publishers Association

- 2018: Lifetime Achievement Award, Greater Los Angeles African American Chamber of Commerce

- 2018: NAACP's Spingarn Medal

- 2024: Inducted into the California Hall of Fame

Filmography

- The Godfather Part III (1990)

- George of the Jungle (1997) as himself, Mayor of San Francisco

- Just One Night (2000)

- The Princess Diaries (2001) as himself, Mayor of San Francisco

- Hulk (2003)

- Pig Hunt (2008)

- America Is Still the Place (2015)

- I'm Charlie Walker (2021)