Withrow Moraine and Jameson Lake Drumlin Field facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Withrow Moraine and Jameson Lake Drumlin Field |

|

|---|---|

The Withrow Moraine erratic on glacial till at the terminus of the Okanogan lobe.

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Douglas County, Washington state |

| Designated | 1986 |

The Withrow Moraine and Jameson Lake Drumlin Field is a special place in Douglas County, Washington state, United States. It's a National Natural Landmark, which means it's a privately owned area recognized by the National Park Service for its amazing natural features. This landmark is important because it shows us how much the Earth changed during the Ice Age.

Here, you can see the only terminal moraine from the Ice Age on the Waterville Plateau. A terminal moraine is like a big pile of rocks and dirt left behind by a glacier when it stops moving. The area also has a drumlin field, which is a group of cool, elongated hills shaped by glaciers as they moved across the land.

Contents

How Was This Place Formed?

The Waterville Plateau: A Land of Ancient Lava

The Withrow Moraine and Jameson Lake Drumlin Field are located on the Waterville Plateau. This plateau is part of the much larger Columbia River Plateau, which covers parts of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Millions of years ago, during the late Miocene and early Pliocene times, this area was covered by huge flows of lava. Imagine one of the biggest lava floods ever seen on Earth! This lava spread out over a massive area, forming what scientists call a large igneous province. Most of this lava erupted between 17 and 14 million years ago.

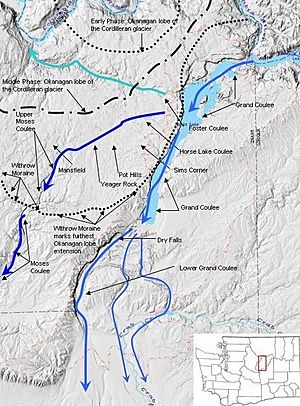

Over time, powerful floods, known as the Missoula Floods, carved through these lava layers. These floods exposed many layers of the basalt (hardened lava) on the edges of the plateau, creating amazing canyons like Grand Coulee and Moses Coulee.

The Ice Age Arrives: Glaciers Shape the Land

About two million years ago, the Pleistocene epoch began, bringing with it the Ice Age. Giant sheets of ice, called glaciers, moved into this region. These glaciers were incredibly powerful. They scraped and smoothed the land, reaching far south into the Waterville Plateau. In some places north of the Grand Coulee, these glaciers were as thick as 3 kilometers (about 10,000 feet)!

You can still see signs of these ancient glaciers today. There are grooves carved into the bedrock (the solid rock beneath the soil) from where the ice moved. You can also find many glacial erratics – large rocks that were carried by the glaciers from far away and then dropped when the ice melted.

The Okanogan Glacier's Journey

One important glacier was the Okanogan lobe, a part of the huge Cordilleran Glacier. This lobe moved down the Okanogan River valley. As it advanced, it covered a large part of the Waterville Plateau. It also blocked the path of the ancient Columbia River.

When the river was blocked, water backed up, creating huge lakes like Glacial Lake Columbia and Lake Spokane. At first, the water from Lake Columbia flowed through the head of Grand Coulee and then down through Foster Coulee to rejoin the Columbia River. But as the glacier moved further south, it blocked Foster Coulee too.

The Columbia River then had to find a new path, which led it through Moses Coulee. But the Okanogan lobe kept growing and eventually blocked Moses Coulee as well! So, the Columbia River had to find yet another way, and this time it carved out what we know today as the modern Grand Coulee.

What Was Left Behind After the Ice Melted?

When the Okanogan lobe glacier finally melted, it left many clues about its journey across the northern Waterville Plateau. The melting ice left behind a thick layer of glacial till, which is a mix of clay, silt, sand, gravel, and even large boulders. In some spots, this till is up to 50 feet thick!

This glacial till, along with many erratic boulders (rocks carried from distant places), covers most of the upper Moses Coulee. The melting water from the glacier flowed down both Moses Coulee and into the Grand Coulee, leaving behind interesting landforms like the Sims Corner eskers and kames. Eskers are long, winding ridges of sand and gravel, and kames are small, cone-shaped hills, all formed by melting glaciers.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |