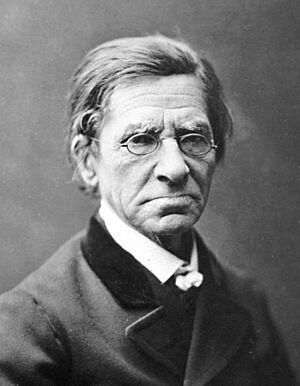

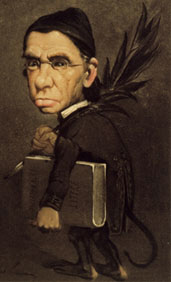

Émile Littré facts for kids

Émile Maximilien Paul Littré (born February 1, 1801 – died June 2, 1881) was a famous French lexicographer, a person who writes or compiles dictionaries. He was also a philosopher and a freemason. He is most famous for his huge dictionary, the Dictionnaire de la langue française, often just called "le Littré".

Life Story of Émile Littré

Émile Littré was born in Paris, France. His father, Michel-François Littré, had been a soldier in the French navy. He was full of new ideas from the French Revolution. Later, his father became a tax collector. He married Sophie Johannot, who also had very open-minded ideas. They focused a lot on Émile's education.

Early Life and Education

Émile went to a school called Lycée Louis-le-Grand. There, he became friends with Louis Hachette and Eugène Burnouf. After finishing school, Émile wasn't sure what job he wanted. He spent time learning English and German. He also studied old languages like Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit. He loved learning about words and languages.

Becoming a Doctor and Teacher

In 1822, Émile decided to study medicine. He passed all his exams and was almost a doctor. But in 1827, his father died. This left his mother without money. Émile immediately stopped his medical studies to help his family. Even though he loved medicine, he started teaching Latin and Greek to earn money. He also attended lectures by a doctor named Pierre François Olive Rayer.

Joining Politics and Journalism

In 1830, Émile became a soldier for the people during the July Revolution. He was part of the National Guard that followed King Charles X. In 1831, he met Armand Carrel, who edited a newspaper called Le National. Carrel hired Émile to read English and German newspapers for interesting stories.

By chance, in 1835, Carrel found out Émile was a great writer. From then on, Émile wrote for the newspaper all the time. He even became its director later.

Marriage and Important Works

In 1836, Littré started writing articles for another magazine, Revue des deux mondes. He got married in 1837. In 1839, the first part of his complete work on Hippocrates was published. Hippocrates was a famous ancient Greek doctor. Because of this excellent work, Émile was chosen to join the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres that same year.

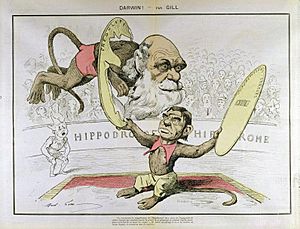

He then discovered the writings of Auguste Comte, a French philosopher. Émile said reading Comte's work was a "turning point" in his life. From then on, Comte's ideas, called positivism, greatly influenced Émile. Émile also helped make positivism popular. He became good friends with Comte and wrote many books about his philosophy.

Émile kept working on his translation of Hippocrates' writings until 1862. He also published a similar work on Pliny's Natural History. After 1844, he joined a committee working on the Histoire littéraire de la France. His knowledge of old French language was very helpful there.

Creating the Great Dictionary

Around 1844, Littré began working on his huge Dictionnaire de la langue française. This dictionary would take him 30 years to finish! He took part in the revolution of July 1848. He also helped stop a group of extreme Republicans in 1849. His essays from this time were put together in a book called Conservation, revolution et positivisme in 1852. These essays showed he fully supported Comte's ideas.

However, as Comte got older, Émile started to see that he couldn't agree with all of his friend's ideas. He kept his different opinions quiet. Comte didn't realize that Émile had grown beyond his teachings, just as Comte himself had grown beyond his own teacher.

His Own Philosophical Ideas

When Comte died in 1858, Littré felt free to share his own thoughts. In 1859, he published his ideas in Paroles de la philosophie positive. Four years later, he wrote a longer book called Auguste Comte et la philosophie positive. This book explained where Comte's ideas came from, through thinkers like Turgot and Kant.

The book praised Comte's life, his way of thinking, and his great contributions. But it also showed where Émile disagreed with him. Émile fully approved of Comte's main philosophy and his ideas about society. He even defended them against another philosopher, John Stuart Mill. However, Émile said that while he believed in a positivist philosophy, he did not believe in a "religion of humanity."

Around 1863, after finishing his translations, he seriously began working on his great French dictionary. He was asked to join the Académie française, a very important French group of scholars. But he said no. He didn't want to be associated with Félix Dupanloup, a bishop who had called him the leader of French materialists. At this time, he also started a magazine called La Revue de philosophie positive with Grégoire Wyrouboff. This magazine shared the views of modern positivists.

Later Life and Politics

Émile Littré's life was mostly about writing until the fall of the Second Empire. Then, he became involved in politics. He felt too old for the difficult Siege of Paris. So, he moved with his family to Brittany. He was asked by Léon Gambetta to give history lectures in Bordeaux. Then, he went to Versailles to become a senator for the Seine area.

In December 1871, he was elected to the Académie française. This happened even though Bishop Dupanloup strongly opposed him again. The bishop even resigned his seat rather than accept Émile.

The Dictionary is Finished

Littré's Dictionnaire de la langue française was finally finished in 1873. It took him almost 30 years! He wrote the draft on over 415,000 sheets of paper. These were stored in eight wooden boxes in his home. This huge effort gave clear definitions and usage examples for every word. It showed all the different meanings words had held over time. When it was published, it was the biggest dictionary of the French language ever made.

Final Years and Beliefs

In 1874, Littré was chosen to be a Senator for life for the Third Republic. During these years, he wrote important political papers. These papers criticized groups that were against the Republic. He also republished many of his old articles and books. One of them was Conservation, révolution et positivisme from 1852. He reprinted it exactly as it was, but added a clear statement that he no longer believed in many of Comte's ideas in it. He also wrote a small book called Pour la dernière fois. In this book, he stated his strong belief in the philosophy of Materialism.

In 1875, he wanted to join a Masonic group called La Clémente Amitié. When asked if he believed in a supreme being, he gave a thoughtful answer. He said that no science denies a "first cause" because it can't find proof against it. He believed that all knowledge is relative. He said we always find unknown things and laws whose causes we don't know. He felt that someone who claims to definitely believe or not believe in a God doesn't fully understand the problem of why things exist.

When it became clear that Émile was very old and wouldn't live much longer, his wife and daughter, who were strong Catholics, tried to convert him. He had long talks with priests. When Émile Littré was close to death, he converted to Catholicism. He was baptized by a priest. His funeral was held following the rules of the Roman Catholic Church. Émile Littré is buried in Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

Works by Émile Littré

Émile Littré wrote and translated many important books during his life.

Translations and New Editions

- Translation of the complete works of Hippocrates (1839–1863)

- Translation of Pliny's Natural History (1848–1850)

- Translation of Strauss's Vie de Jésus (1839–1840)

- Translation of Müller's Manuel de physiologie (1851)

- New edition of the political writings of Armand Carrel, with notes (1854–1858)

Dictionaries and Books on Language

- Reprise du Dictionnaire de médecine, de chirurgie, etc. with Charles-Philippe Robin, of Pierre-Hubert Nysten (1855)

- Histoire de la langue française (History of the French Language) (1862)

- Dictionnaire de la langue française ("Le Littré") (1863–1873)

- Comment j'ai fait mon dictionnaire (How I Made My Dictionary) (1880)

Books on Philosophy

- Analyse raisonnée du cours de philosophie positive de M. A. Comte (1845)

- Application de la philosophie positive au gouvernement (1849)

- Conservation, révolution et positivisme (1852, 2nd ed., with supplement, 1879)

- Paroles de la philosophie positive (1859)

- Auguste Comte et la philosophie positive (1863)

- La Science au point de vue philosophique (Science from a Philosophical Viewpoint) (1873)

- Fragments de philosophie et de sociologie contemporaine (1876)

Other Writings

- Études et glanures (Studies and Gleanings) (1880)

- La Verité sur la mort d'Alexandre le grand (The Truth About the Death of Alexander the Great) (1865)

- Études sur les barbares et le moyen âge (Studies on Barbarians and the Middle Ages) (1867)

- Médecine et médecins (Medicine and Doctors) (1871)

- Littérature et histoire (Literature and History) (1875)

- Discours de reception à l'Académie française (Acceptance Speech at the Académie française) (1873)

See also

In Spanish: Émile Littré para niños

In Spanish: Émile Littré para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |