Public Schools Battalions facts for kids

The Public Schools Battalions were special groups of soldiers in the British Army during World War I. They were part of Kitchener's Army, formed in 1914. At first, only boys who had attended public schools or universities could join.

These battalions were unique. Many of the young men who joined were encouraged to become officers because the army needed them. As more officers were needed, the battalions started accepting regular volunteers and later, conscripts (people forced to join). This meant they lost their "exclusive" feel, even though they kept their original names.

Two of these battalions fought bravely on the Western Front. One of them faced terrible losses on the first day of the Somme. After tough service, both battalions were officially closed down in February 1918, before the war ended.

Contents

Joining the Army: Recruitment Efforts

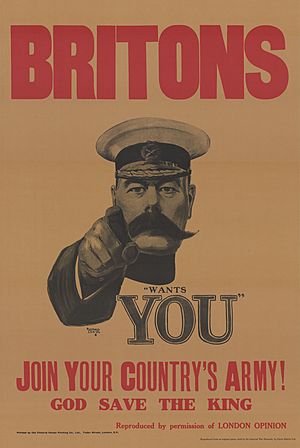

Just two days after Britain declared war in August 1914, Parliament agreed to add 500,000 men to the army. Earl Kitchener, the new Secretary of State for War, made a famous call: 'Your King and Country Need You!' He asked for the first 100,000 volunteers.

This first group of soldiers became known as Kitchener's First New Army, or 'K1'. So many people volunteered that the army struggled to organize them all. Many units were created by local groups across the country. The idea of "Pals battalions"—where friends could serve together—became very popular. One of the first was the 'Stockbrokers Battalion' in London. These local and "Pals" battalions formed Kitchener's Fifth New Army, or 'K5'.

One important unit was started by Major J.J. Mackay and some businessmen in Harrow-on-the-Hill. They decided to create a battalion just for former public schoolboys and university students. They opened a recruiting office in London in September 1914. Over 1,500 people applied, even retired officers who wanted to serve as regular soldiers. Many men wanted to fight alongside their friends as private soldiers, not as officers. Some recruits were even international rugby union and football players! This group became the 16th (Service) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge's Own), often called the 'PSB'.

On September 15, volunteers went to Kempton Park Racecourse for training. The idea was so successful that four more Public Schools battalions were formed. These gathered at Epsom Downs Racecourse and joined the Royal Fusiliers.

16th (Service) Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (Public Schools)

Quick facts for kids 16th (Service) Battalion, Middlesex Regiment (Public Schools) |

|

|---|---|

Cap badge of the Middlesex Regiment

|

|

| Active | 4 September1914 – 11 February 1918 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 1 Battalion + Reserve Battalion |

| Part of | 33rd Division 29th Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Kempton Park Racecourse |

| Engagements | Beaumont-Hamel Arras Third Ypres Cambrai |

Getting Ready: Training and Early Days

At first, the battalion wore blue uniforms and used old Long Lee-Enfield rifles. This was because there weren't enough khaki uniforms or modern rifles. Many recruits already knew how to use the old rifles from their school cadet training.

A regular officer, Lt-Col J. Hamilton Hall, took command. In January 1915, the battalion moved to a camp in Woldingham, Surrey. By the end of 1914, 360 men from the battalion had become officer candidates. Many new volunteers from across the British Empire replaced them.

In November 1915, the 33rd Division, which included the 16th Middlesex, arrived in France. They joined the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). In December, they took over trenches in the La Bassée area. This was considered a "quiet" sector, good for new units to learn about trench warfare.

During their first time in the trenches in January, the battalion had its first casualties. They lost one officer and 11 other soldiers, with 24 wounded, from a single shell. Later, they suffered more losses during a failed attack on enemy positions.

In February, the Public Schools Battalions were moved to Saint-Omer. Their best men were chosen to become officers. The 16th Middlesex provided 250 candidates. The rest of the battalion was then quarantined due to an outbreak of German Measles.

In April, the battalion, now with new recruits, joined the 29th Division at Doullens. They replaced an Irish battalion that couldn't get enough new soldiers.

The Somme: A Tragic Day

The 29th Division was preparing for the "Big Push"—the Battle of the Somme—set for July 1916. Their goal was to cross 350 yards of open ground and capture Beaumont-Hamel. They also aimed to take the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt with the help of a huge mine. The 16th Middlesex helped carry away chalk from the tunnels being dug.

The plan relied on five days of artillery fire to destroy enemy trenches and barbed wire. But bad weather meant the wire wasn't cut. So, the attack was delayed until July 1.

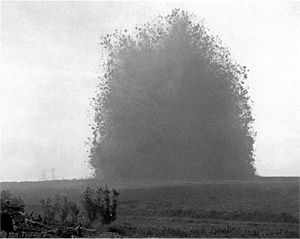

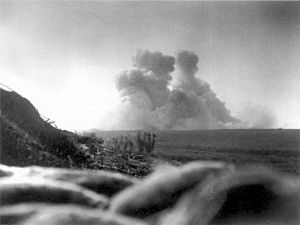

Controversially, the Hawthorn Ridge mine was blown up at 7:20 AM, ten minutes before the main attack. This gave the Germans time to recover before the soldiers went "over the top." A cameraman, Geoffrey Malins, filmed the explosion. It was later shown in his famous film, The Battle of the Somme.

On July 1, the 16th Middlesex moved into their trenches. The first wave of attackers faced heavy machine gun fire and artillery. The second wave, including men from the 16th Middlesex, couldn't leave their trenches until 7:55 AM. They also faced intense fire. The 16th Middlesex almost reached the wire in front of the crater but suffered huge losses. Malins' film shows a group of men, thought to be from the 16th Middlesex, reaching the crater and then retreating.

The attack failed. The 16th Middlesex lost 22 officers and about 500 soldiers. This was one of the highest casualty lists of the day. Only one frontline officer from the attacking companies remained. Many men from the 16th Middlesex are buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's Hawthorn Ridge Cemetery No 1. Others are remembered on the Thiepval Memorial for the missing.

After this terrible battle, the 29th Division was sent to the Ypres Salient to rebuild. They returned to the Somme in October for trench duty.

Fighting On: Arras, Ypres, and Cambrai

In April 1917, the 29th Division moved north for the Arras Offensive. They attacked on April 23. A German counter-attack disrupted their plans, but the 16th Middlesex helped hold a trench against the enemy.

In July, the division moved north again for the Third Ypres Offensive. The battalion suffered more casualties in August. Their commanding officer, Lt-Col Frank Morris, was killed just two days after taking command.

The battalion continued to face heavy fighting at the Battles of Polygon Wood and Broodseinde in September and October, suffering losses but not making direct attacks.

In October, the 29th Division moved south to train for a big tank attack on the Hindenburg Line—the Battle of Cambrai. The attack began on November 20. The 16th Middlesex, following tanks, helped capture Couilet Wood and Marcoing. They even captured a bridge across the St Quentin Canal.

The next day, the Germans launched a strong counter-attack at Noyelles. The 16th Middlesex, along with other units, fought hard in fierce street battles. With the help of two tanks, they drove the Germans out.

The Battle of Cambrai soon became a stalemate. On November 30, the Germans launched a massive counter-attack. The 16th Middlesex held their positions at Mon Plaisir Farm. They used their rifles and Lewis guns to stop the Germans, who had broken through a nearby brigade. The battalion's commanding officer, Lt-Col Forbes-Robertson, even though wounded and blinded, visited all positions to encourage his men.

The 86th Brigade, including the 16th Middlesex, faced the main German attacks on December 1. They were in a difficult position and had to withdraw. They evacuated all wounded and carried as much ammunition as possible, dumping the rest into the canal. The withdrawal was completed by 4:00 AM on December 2.

The End: Disbandment

By early 1918, the British army had a severe shortage of soldiers. About one in four infantry battalions had to be disbanded. Their remaining soldiers were sent to other units.

After its last trench duty in January, the 16th Middlesex was ordered to disband. Its soldiers were sent to other Middlesex Regiment battalions. On February 11, the battalion was officially closed down.

24th (Reserve) Battalion, Middlesex Regiment

When the 16th Middlesex went to camp, two companies stayed behind at Woldingham. These later formed the 24th (Reserve) Battalion in September 1915. Their job was to train and supply new soldiers for the main battalion.

This reserve battalion moved around, eventually becoming the 100th Training Reserve (TR) Battalion. It was later renamed the 256th (Infantry) Bn of the TR. In October 1917, it became the 52nd (Graduated) Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, training 18–19-year-olds. It was finally disbanded in March 1920, after the war ended.

18th–21st (Service) Battalions, Royal Fusiliers (1st–4th Public Schools)

| 18th–21st (Service) Battalions, Royal Fusiliers (1st–4th Public Schools) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 11 September 1914 – 16 February 1918 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 4 Battalions + 2 Reserve Battalions |

| Part of | 33rd Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Epsom |

| Engagements | High Wood Arras Polygon Wood |

The four Public Schools Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers were formed at Epsom Downs Racecourse in September 1914:

- 18th (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (1st Public Schools)

- 19th (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (2nd Public Schools)

- 20th (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (3rd Public Schools)

- 21st (Service) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers (4th Public Schools)

Their training was similar to the 16th Middlesex. At first, there weren't enough experienced officers to train them. The 20th and 21st Battalions camped in Ashtead and Leatherhead during the winter of 1914–1915.

These four battalions formed the 118th Brigade. In April 1915, they became part of the 33rd Division and were renumbered as the 98th Brigade. By July 1915, they were at Clipstone Camp and later moved to Salisbury Plain for final battle training.

Fighting on the Western Front

In November 1915, the 98th Brigade arrived in France. However, the 18th and 20th Battalions were immediately sent to another brigade. After a short time learning about trench warfare, the 18th, 19th, and 21st Battalions were transferred and then disbanded in April 1916. Most of their soldiers became officers.

The remaining battalion, the 20th (3rd Public Schools), continued to serve. Captain Robert Graves, a famous writer who served in the same brigade, was critical of this battalion. He said that most of their best men had left to become officers, leaving behind those "unfitted to hold commissions." He even described an incident where a large patrol from the battalion got lost in No man's land.

After conscription (forced military service) started in 1916, the special nature of all "Pals" battalions changed as the war continued.

Somme and Arras Battles

In July 1916, the 33rd Division, including the 20th Royal Fusiliers, moved south to reinforce the army fighting on the Somme. They fought in the Attacks on High Wood. On July 20, the 20th Royal Fusiliers fought hard to clear the southern part of the wood. They reached the northern part after more fighting but were pushed back by heavy shelling. They suffered many casualties holding their positions.

The 33rd Division rested until August, then returned to the High Wood area. In October, during the Battle of Le Transloy, the division captured some trenches. The 20th Royal Fusiliers, commanded by Lt-Col W.B. Garnett, had to move supplies through 5,000 yards of thick mud to the front line.

In March 1917, the 33rd Division fought against German rearguards as the Germans pulled back to the Hindenburg Line. They then joined the Arras Offensive. The 20th Royal Fusiliers made an unsuccessful attempt to push into the Hindenburg Line in April. Casualties were heavy during April and May.

In the summer, the 33rd Division moved to Nieuport on the Flanders coast. They spent three weeks under constant shellfire and air raids. By late August, it was clear that the main offensive wasn't breaking through, so units were sent to the Ypres Salient to help.

Ypres and Disbandment

Elements of the division entered the line in the Ypres sector in September. The whole division then joined the Battle of Polygon Wood on September 26. They had to fight off a German attack the day before, which disrupted their own plans.

In November 1917, the 33rd Division moved north of Ypres to take over the Passchendaele Salient. They spent the winter months in this area, which was known as one of the worst on the Western Front. It was a sea of mud with no cover, terrible paths, and constant shelling, especially with mustard gas.

Like the 16th Middlesex, the 20th Royal Fusiliers was disbanded between February 2 and 15, 1918. Its officers and soldiers were sent to other battalions.

28th and 29th (Reserve) Battalions, Royal Fusiliers

When the four Royal Fusiliers Public Schools battalions went to camp, their depot companies stayed at Epsom. In August 1915, these formed two reserve battalions:

- 28th (Reserve) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers – from 1st and 2nd Public Schools

- 29th (Reserve) Battalion, Royal Fusiliers – from 3rd and 4th Public Schools

These reserve battalions moved to Oxford and then to Edinburgh. In September 1916, they became the 104th and 105th Training Reserve Battalions. The 105th TR Battalion was disbanded in December 1917. The 104th TR Battalion became the 53rd (Young Soldier) Bn of the Royal Fusiliers in November 1917. It was finally absorbed into another battalion in April 1919, after the Armistice.

Images for kids