British Army during the First World War facts for kids

The British Army during the First World War fought its biggest and most expensive war ever. Unlike the French and German Armies, the British Army started the war with only volunteers, not soldiers forced to join (called conscripts). The British Army was also much smaller than the French and German armies.

During the First World War, there were four main types of British armies. First, the regular army had about 247,000 soldiers. Many of these were stationed overseas to protect the British Empire. They were supported by about 210,000 reserve soldiers. This group formed the main part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sent to France. Second, the Territorial Force had about 246,000 soldiers. They were first meant for home defense but later helped the BEF after many regular soldiers were lost. Third, Kitchener's Army was made up of men who volunteered in 1914–1915. They first fought in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Fourth, after compulsory service started in January 1916, existing armies were reinforced with conscripts.

By late 1918, the British Army had grown to 3,820,000 men. It could send over 70 divisions to fight. Most of the British Army fought on the Western Front in France and Belgium against the German Empire. Some units also fought in Italy and Salonika against Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. Others fought in the Middle East, Africa, and Mesopotamia against the Ottoman Empire. One group even fought with the Japanese Army in China during the Siege of Tsingtao.

The war was also tough for army commanders. Before 1914, no British General in the BEF had commanded a group larger than a division in battle. The army grew so fast that some officers became corps commanders in less than a year. Commanders also had to learn new tactics and use new weapons. As fighting changed from moving battles to trench warfare, infantry and artillery had to learn to work together. Later, the Machine Gun Corps and the Tank Corps joined, and new ways of fighting were developed to include them.

Soldiers at the front faced many problems. Food was often short, and diseases spread easily in the wet, rat-filled trenches. Besides enemy attacks, many soldiers got new illnesses like trench foot, trench fever, and trench nephritis. When the war ended in November 1918, about 673,375 British Army soldiers were killed or missing. Another 1,643,469 were wounded. After the war, the army quickly sent soldiers home. Its strength dropped from 3,820,000 men in 1918 to 370,000 by 1920.

Contents

How the Army Was Set Up

The British Army's structure during World War I was shaped by the needs of the British Empire and earlier wars. It relied on volunteers and a regimental system. This system had been improved by the Cardwell and Childers Reforms in the late 1800s. The army was mainly set up for protecting the Empire and fighting colonial wars.

A big war, the Second Boer War (1899–1902), showed that the army needed to improve its tactics and leadership. After this, the Haldane Reforms in 1907 created an Expeditionary Force of seven divisions. They also changed the volunteers into a new Territorial Force and the old militia into the Special Reserve. These changes helped the army be ready for a big war.

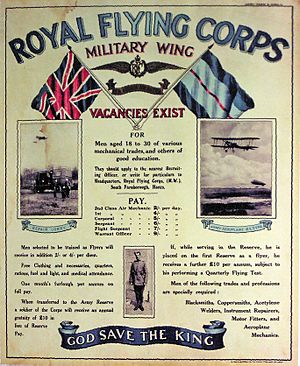

When the war started in August 1914, the British regular army was a small, professional force. It had about 247,432 regular troops. These included different regiments of Guards, infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Almost half of the regular army was stationed overseas in different parts of the British Empire. The Royal Flying Corps, which had 84 aircraft, was also part of the British Army until 1918.

The regular army was supported by the Territorial Force, which had about 246,000 men. They were used for home defense at the start of the war. There were also three types of reserves. The Army Reserve had soldiers who had finished their regular service. The Special Reserve was for part-time soldiers. The National Reserve had men with military experience who could volunteer if needed.

Even with all these groups, only about 150,000 men were immediately ready for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sent to Europe. In comparison, the French Army had 1,650,000 troops, and the German Army had 1,850,000 troops in 1914.

Britain started the war with six regular and fourteen territorial infantry divisions. During the war, many more divisions were formed, including those from Kitchener's Army and the Royal Navy.

Army Divisions and Their Changes

In 1914, each British infantry division had three infantry brigades. Each brigade had four battalions, with two machine guns per battalion. They also had artillery, engineers, and support units.

The cavalry division had 15 cavalry regiments. Unlike French and German cavalry, British cavalry used rifles, not just shorter carbines. They also had more artillery. Over the war, the infantry divisions changed. They got more machine guns and mortars. The army adapted to new fighting styles, from mobile warfare to static trench warfare. The number of cavalry soldiers decreased, while engineers became more important.

British Expeditionary Force (BEF)

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was the main British army sent to France. It started with six infantry divisions and five cavalry brigades. These were organized into two Army corps. The British Indian Army also sent many officers and soldiers to help.

By the end of 1914, after battles like Mons and Ypres, most of the original regular British Army was gone. However, they had stopped the German advance.

The BEF grew quickly. By December 1914, it had five army corps. As regular soldiers were lost, the army was filled by the Territorial Force and then by Lord Kitchener's New Army volunteers. By March 1915, there were 29 new divisions. More armies were formed, like the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Armies.

Joining the Army

In August 1914, 300,000 men volunteered to fight. Another 450,000 joined by the end of September. Many joined "Pals battalions," where friends and co-workers could serve together. This meant that when these battalions suffered losses, whole communities back home were deeply affected.

Conscription (compulsory military service) for single men started in January 1916. Men aged 18 to 41 had to join the army unless they were married or worked in certain jobs. This law did not apply to Ireland. Conscription was extended to married men in May 1916. By the end of 1918, the army reached its peak strength of four million men. About 2.6 million men had volunteered, and another 2.3 million were conscripted.

Women also volunteered in non-fighting roles. By the end of the war, 80,000 women had joined. They mostly worked as nurses in groups like the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS). From 1917, they could join the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). Most WAAC members stayed in Britain, but about 9,000 served in France.

Army Leaders

In 1914, no British officer in the BEF had commanded a group larger than a division in battle. The first Commander-in-Chief of the BEF was Field Marshal John French. His last command had been a cavalry division in the Second Boer War.

Douglas Haig commanded the British I Corps. He was also a cavalryman. After the failed attack at the Battle of Loos in 1915, Haig replaced French as commander of the BEF. He led the army for the rest of the war, including famous battles like the Somme and battle of Passchendaele.

General Herbert Plumer became a corps commander in December 1914. He later commanded the Second Army in 1915. He was known for his victory at the Battle of Messines in 1917. Plumer is seen as one of the most effective British commanders on the Western Front.

General Edmund Allenby commanded the Cavalry Division in 1914. He later led the Third Army on the Western Front. In 1917, he took command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force. He led the capture of Palestine and Syria.

General Julian Byng started the war commanding a cavalry division. He later led the Canadian Corps. His most famous battle was the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917.

General Henry Rawlinson commanded the Fourth Army in 1916. He was known for using new tactics. He combined tank and artillery attacks during the Battle of Amiens.

General Hubert Gough commanded the Fifth Army. His army suffered heavy losses at the battle of Passchendaele. He was later replaced by General William Birdwood.

Officer Selection

In 1914, the British Army had about 28,060 officers. By November 1918, this number grew to 164,255. Most pre-war officers came from wealthy families with military backgrounds.

During the war, many new officers were needed. Lord Kitchener asked for volunteers and experienced soldiers to become officers. Most volunteers came from the middle class. Promotion could be very fast. For example, A. S. Smeltzer became a second lieutenant in 1915 and a lieutenant colonel by 1917.

The war also meant that battalion commanders became much younger. In 1914, they were over 50. By 1917-1918, the average age was 28. It became official policy that men over 35 could not command battalions.

Army Training and Weapons

In 1925, a British historian said that the British Army of 1914 was "the best trained, best equipped and best organized British Army ever sent to war." This was partly due to the Haldane reforms. Soldiers trained year-round, from individual skills to large army exercises.

The Second Boer War taught the army about the dangers of long-range rifles. So, soldiers learned to advance in spread-out lines, use cover, and work with artillery. They also practiced "fire and movement" tactics.

Cavalry practiced scouting and fighting on foot. They were the only major European cavalry trained for both mounted charges and dismounted action. They also carried the same rifles as infantry.

British infantry were excellent marksmen. In 1914, their rifle fire was so effective that Germans sometimes thought they were facing many machine guns. Soldiers practiced shooting to fire 15 effective rounds a minute at 300 yards. They also learned to act on their own without constant orders from officers.

Weapons Used

The main rifle was the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield Mk III (SMLE Mk III). It was a bolt-action rifle that allowed trained soldiers to fire 20–30 accurate rounds per minute.

The heavy Vickers machine gun was very reliable. In one famous event, 10 Vickers guns fired almost a million rounds in 12 hours, using all available water to keep them cool. All guns worked perfectly afterward.

The lighter Lewis gun was adopted in October 1915. It was faster to build and easier to carry than the Vickers. By the end of the war, Lewis Guns were very common on the Western Front.

The British also used mortars. The 2-inch medium mortar was used first, then replaced by the 81mm Stokes Mortar in late 1915.

Finally, the Mark I tank was a British invention designed to break the stalemate of trench warfare. It first appeared on the Somme in September 1916.

Infantry Tactics

After the "race to the sea," fighting changed to trench warfare. The British Army was not ready for this. They lacked barbed wire, hand grenades, and trench mortars.

In early trench warfare, infantry attacks involved many waves of soldiers. They would move slowly, carrying their rifles, bayonets, gas masks, ammunition, and other gear.

By 1918, tactics had changed. Infantry no longer advanced in straight lines. They moved in flexible waves, using darkness and shell holes for cover. Skirmishers went first, followed by the main waves. Each platoon had a Lewis gun section and a grenade section. They supported each other with fire and moved forward without stopping. Grenades were used to clear trenches and dugouts.

Tank Tactics

Tanks were meant to break the trench stalemate. In their first use on the Somme, they were used in small groups with infantry escorts. Many broke down or were damaged.

In 1917, at the Battle of Cambrai, the Tank Corps used new tactics. Three tanks would advance in a triangle, protecting infantry. Tanks would break barbed wire and attack German strong points. This battle showed how effective tanks and infantry could be when working together.

By 1918, tanks were used more widely. One tank would cover every 100 or 200 yards. They would engage enemy strong points, forcing defenders into shelter for the infantry to deal with.

Artillery Tactics

Before the war, artillery worked alone. In 1914, the heaviest gun was the 60-pounder. By 1918, artillery was the most powerful force on the battlefield. The number of artillery units grew hugely.

To move heavy guns, the army used Holt caterpillar tractors. They also put naval guns on railway platforms for long-range support.

Artillery learned to fire indirectly, using observers and complex calculations. The "barrage" became a key tactic. This was a line of shells fired to protect advancing infantry.

The "creeping barrage" moved forward slowly, just ahead of the infantry. This kept the element of surprise and prevented defenders from recovering. Infantry were trained to follow very close behind their own shells. This tactic was very effective in battles like the Second Battle of Arras.

Once infantry reached enemy trenches, the artillery would switch to a "standing barrage" to protect them from counter-attacks. A "box barrage" would surround an area to isolate it. SOS barrages were fired in response to enemy counter-attacks, often signaled by flares.

Later in the war, artillery also focused on destroying enemy artillery using "counter-battery fire." New methods like sound ranging helped locate enemy guns. It was found that short, intense bombardments followed by infantry attacks were more effective than long ones.

Communications

The Royal Engineers Signal Service handled all communications. This included messengers, telegraph, telephone, and later wireless radio. At first, civilian telephones were used, but they broke easily. Special field telephones were designed for war. These could send voice or Morse code messages.

Visual signals like semaphore flags and lamps were also used. However, operators had to expose themselves to enemy fire.

Animals were also used for communication. Dogs carried messages. Horses and mules laid cables. Carrier pigeons carried messages from the front line, even from inside tanks. Over 20,000 pigeons were used.

Royal Flying Corps

At the start of the war, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had five squadrons. They first used planes for spotting enemy positions in September 1914. They became more effective with wireless communication and aerial photography in 1915.

The RFC's role grew from scouting to fighting for control of the air and bombing targets. Early British planes were not as good as German ones. In April 1917, known as Bloody April, the RFC lost many aircrew and planes. Later in 1917, new planes like the Sopwith Camel helped them compete better.

In April 1918, the RFC joined with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) to form the new Royal Air Force (RAF). By 1919, the RAF had 4,000 combat aircraft and 114,000 personnel.

Royal Engineers

The Royal Engineers grew from 25,000 men in 1914 to 250,000 in 1917. They had field companies attached to each infantry division and signals companies for communication.

Royal Engineer tunnelling companies were formed to dig tunnels and mines. They dug subways, cable trenches, and dugouts. They also carried out offensive mining, like creating the Lochnagar Crater on the first day of the Somme. Engineers were also responsible for maintaining buildings, fortifications, railways, roads, and water supply.

Machine Gun Corps

The Machine Gun Corps (MGC) was formed in September 1915. It provided specialist machine-gun teams for infantry brigades. In the trenches, their guns were placed to create overlapping fields of fire, making them very strong defensive weapons. They also fired over the heads of advancing infantry to stop enemy reinforcements.

Tank Corps

The Tank Corps was formed in 1916. Tanks were first used in the Battle of the Somme on 15 September 1916. They were meant to crush barbed wire and cross trenches to help infantry break through enemy lines.

In November 1916, tank companies were reorganized into battalions. Each battalion had 32 officers and 374 men. Tanks were mainly used on the Western Front. The Battle of Cambrai in 1917 was the first time many tanks were used together. The Battle of Amiens in 1918 showed how valuable tanks were. By September 1918, the British Army was the most mechanized army in the world.

Army Service Corps

The Army Service Corps (ASC) managed the transport system. They delivered soldiers, ammunition, and supplies to the front. The ASC grew from 12,000 men to over 300,000 by November 1918. They also managed many laborers from India, Egypt, and China.

Royal Army Medical Corps

The Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) provided doctors, evacuated casualties, and ran field hospitals. They were helped by volunteers from the British Red Cross and St John's Ambulance.

Captain Noel Godfrey Chavasse was the only person to win the Victoria Cross twice during the war. He was a doctor in the RAMC.

Life in the Trenches

By the end of 1914, the war on the Western Front became a stalemate, with long lines of trenches. By September 1915, the British front line was about 70 miles long. Soldiers usually spent about eight days in the front or reserve trenches before being relieved.

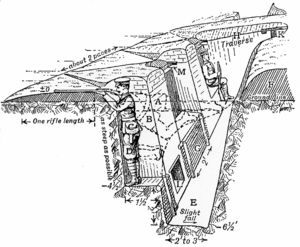

A typical front line had three trenches: the fire trench, the support trench, and the reserve trench. All were connected by communication trenches. Trenches were usually four or five feet deep. In wet areas, sandbags were used to build walls. Fire trenches had a step for soldiers to stand on and shoot. Duckboards lined the bottom to keep men out of the mud. Dugouts were cut into the walls for shelter, though officers usually got the best ones. Soldiers often slept wherever they could, sometimes under groundsheets in the mud.

Soldiers were always in danger from shells, mortars, and bullets. Later, they also faced air attacks. Even in quiet areas, soldiers could be hurt by snipers, artillery, or disease. The harsh conditions, with wet, muddy trenches, lice, and rats, caused many illnesses. Soldiers suffered from trench foot, trench fever, trench nephritis, frostbite, and heat exhaustion. Food was often cold or didn't arrive at all because cooking smoke would attract enemy fire.

Daily Routine in the Trenches

The day started with "stand-to" an hour before dawn. Everyone manned their positions to guard against a surprise attack. After stand-to, men had breakfast and cleaned themselves. Then, they were given daily chores like cleaning rifles, filling sandbags, or digging latrines. When off-duty, men tried to sleep, but sleep deprivation was common due to constant bombardments. Soldiers also took turns on sentry duty.

During daylight, movement was limited because of enemy snipers. Most work happened after dark. Rations and water were brought to the front. Fresh units replaced tired ones. "Trench raiding" parties went into no man's land to gather information or capture prisoners. Construction parties repaired trenches and barbed wire. An hour before dawn, everyone would stand-to again.

Moving into the Front Line

When a division moved to the front line, officers would first scout the area. Transport officers learned how to get food and ammunition to the troops. Artillery detachments moved forward to join existing batteries. Five days later, specialists from the infantry battalions moved in to take over trench supplies. Overnight, the battalions would move into their positions.

Discipline in the Army

The army had strict rules, especially during wartime. Lesser offenses were handled by commanding officers. They could fine men, give them extra duties, or demote them. More serious offenses were dealt with by courts martial.

"Field punishment" (FP) was a common punishment. FP No.1 involved shackling a man to a fixed object. This was very unpleasant, especially in bad weather. FP No.2 meant a man was shackled but not fixed in place.

Courts Martial and Executions

Soldiers who committed serious offenses were tried by Field General Court Martial. These courts had strict rules. The accused could object to the court's makeup and have an officer defend them. Most cases were for offenses like being absent without leave, drunkenness, or disobedience. Prison sentences were often suspended to encourage good behavior.

Of the 3,080 men sentenced to death, 346 were actually executed. Most of these (266) were for desertion. Other reasons included murder and cowardice. It was believed that making an example of deserters was necessary to maintain discipline. Desertion usually meant being away for 21 days or showing intent not to return.

In later years of the war, families of executed men were often told that their loved ones had died in battle. Their families still received pensions. In 2006, the British government pardoned all men executed for certain offenses during World War I, recognizing them as victims.

Shell Shock

At the time, Posttraumatic stress disorder (called "shell shock") was starting to be understood. It was seen as a war injury. While some soldiers tried to fake it, medical staff generally did not execute soldiers who were truly suffering from shell shock. However, understanding of mental trauma was still very limited.

Positive Motivation

Soldiers were also motivated by positive things. New medals were created, like the Military Cross and the Military Medal, to reward bravery. Medals were often awarded quickly so soldiers could receive them.

To keep morale up, events like race meetings, concerts, and football matches were organized. Unofficial newspapers, like the "Wipers Times," gave soldiers a way to express their views.

Fighting on the Western Front

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) arrived in France soon after war was declared. Their first battle was at Mons on 23 August 1914. After this, the Allies began a long retreat. The BEF helped stop the German advance at the First Battle of the Marne. Then came the "Race to the Sea," where both sides tried to outflank each other. For the BEF, 1914 ended with the "First Ypres," which started a long fight for the Ypres Salient. The BEF suffered huge losses, with many infantrymen killed or wounded.

In 1915, Trench warfare became common. The BEF fought smaller battles, sometimes with French offensives. These included the Battle of Neuve Chapelle and the Battle of Aubers Ridge. In April 1915, the German Army used poison gas for the first time at the Second Battle of Ypres. By September 1915, the BEF had grown with the arrival of Kitchener's New Army divisions. They launched a major attack, the Battle of Loos, using their own chemical weapons. This battle's failure led to Field Marshal French being replaced by General Sir Douglas Haig in December 1915.

The year 1916 was dominated by the Battle of the Somme, which began terribly on 1 July. The first day on the Somme was the bloodiest day in British Army history, with 19,240 soldiers killed. The battle continued for four-and-a-half months, costing 420,000 British casualties.

In February 1917, the German Army pulled back to the strong Hindenburg Line. The BEF attacked these defenses in the Battle of Arras in April. British troops made good advances but couldn't achieve a major breakthrough. Haig then launched an offensive in Flanders. General Herbert Plumer's Second Army successfully captured the Messines ridge. The Battle of Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypres) began on 31 July 1917. It was one of the toughest battles, turning the battlefield into a muddy swamp. The BEF suffered around 310,000 casualties. The year ended with the Battle of Cambrai, which showed the power of tanks used in large numbers.

The final year of the war, 1918, started with disaster but ended in victory. On 21 March 1918, Germany launched the Spring Offensive. The main attack hit General Gough's Fifth Army, forcing it to retreat. French General Ferdinand Foch became the Supreme Commander of Allied forces. The BEF fought hard, and Field Marshal Haig issued his famous order, "With our backs to the wall... each one of us must fight on to the end."

On 8 August, General Rawlinson's Fourth Army launched the Battle of Amiens. This began the Hundred Days Offensive, the final Allied push. All five armies of the BEF went on the attack. Fighting continued until the Armistice on 11 November 1918. In these final attacks, the BEF captured 188,700 prisoners and 2,840 guns.

Other Campaigns Around the World

The British Army also fought in other parts of the world.

Ireland

The Easter Rising was a rebellion in Ireland during Easter Week 1916. Irish republicans wanted to end British rule in Ireland. The rising lasted from 24 to 30 April 1916. Rebels seized key locations in Dublin. The British Army sent reinforcements and put down the rebellion after seven days. Its leaders were tried and executed.

Salonika

A new front opened in Salonika, Greece, to support Serbian forces against Bulgaria. British, French, and Russian troops arrived between 1916 and 1917. They became known as the Allied Army of the Orient. They launched an offensive in April 1917 but had little success. The front became a stalemate until September 1918, when the British and Greek Armies attacked. Bulgaria signed an armistice soon after.

Italy

Italy joined the Allies in May 1915. The British Army's involvement in Italy started in late 1917. British and French divisions were sent to help after the Italian army suffered a big defeat at the battle of Caporetto. The reinforced Italians stopped the Austro-Hungarian advance. In October 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Army collapsed after heavy losses, and an armistice was signed.

China

In 1914, the British Army helped Japanese forces capture the German port of Tsingtao in China. The 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers were part of a 23,000-strong force. The port was captured in November 1914.

East Africa

The East African Campaign began in 1914 against German and African forces. Most British operations were carried out by African, South African, or Indian Army units. The German forces remained undefeated until they surrendered on 25 November 1918, after the Armistice in Europe. Many troops died from diseases rather than enemy action.

Gallipoli

Turkey joined Germany in October 1914, closing the Dardanelles Straits. In April 1915, British and ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand) forces landed on the Gallipoli peninsula. They fought a series of battles against Turkish defenses, but all failed. Another landing was made in August, but it also failed to achieve its goals. By January 1916, the Allies had withdrawn. Of the 480,000 Allied troops involved, 44,000 died, with 20,000 being British.

Mesopotamia

The British force in Mesopotamia was mainly from the British Indian Army. Their goal was to protect the Royal Navy's oil supply from Persia. In November 1914, the British force invaded Mesopotamia and entered Basrah. However, they suffered a big defeat at the Siege of Kut-al-Amara in 1916, where 13,000 British and Indian troops surrendered. The British reorganized, and a new offensive began in December 1916. They recaptured Kut-al-Amara and Baghdad in 1917. The campaign continued until October 1918, leading to the collapse of Turkish forces. About 100,000 British and Indian casualties occurred, with 53,000 deaths, many from disease.

Sinai and Palestine

The British Army in the Sinai and Palestine campaign aimed to protect the Suez canal. General Sir Archibald Murray made steady progress against Turkish forces, winning battles like Romani. However, he was stopped at the first and second battle of Gaza in 1917. General Sir Edmund Allenby replaced Murray and revitalized the campaign.

Allenby reorganized his forces. In October 1917, they defeated the Turkish forces in the third battle of Gaza, leading to the capture of Jerusalem in December 1917. In September 1918, Allenby's forces won the decisive Megiddo Offensive. This led to the Armistice of Mudros with the Ottoman Empire in October 1918. Total Allied casualties were 60,000, with 20,000 killed.

After the War

The British Army during the First World War was the largest military force Britain had ever put into the field. On the Western Front, the British Expeditionary Force ended the war as a very strong fighting force.

The cost of victory was high. Official figures show that between August 1914 and September 1919, 673,375 British soldiers were killed or missing. Another 1,643,469 were wounded. For some, the fighting continued after 1918. The British Army sent troops to Russia during the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. This was followed by the Anglo-Irish War and the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

The army quickly sent 4,000,000 men home after the war. Within a year, the British Army was reduced to 800,000 men. By November 1920, it had fallen to 370,000 men.

The Ten Year Rule was introduced in 1919. It said that the British Armed Forces should plan their budgets assuming no major war for the next ten years. This led to big cuts in defense spending. The British Army tried to learn from World War I and create a small, mechanized, professional army. However, without a clear threat, its main job became garrison duties around the British Empire.