1933 British Mount Everest expedition facts for kids

The 1933 British Mount Everest expedition was the fourth time British climbers tried to reach the top of Mount Everest. It was their third attempt to be the first to climb the world's highest mountain. Previous expeditions in 1922 and 1924 had not succeeded.

Just like the earlier tries, the 1933 expedition didn't reach the summit. However, two climbers, Lawrence Wager and Percy Wyn-Harris, and later F. S. Smythe, set a new record for climbing without extra oxygen. This record stood until 1978! During Wager and Wyn-Harris's climb, they found an ice-axe. It belonged to Andrew Irvine, who disappeared with Mallory during their summit attempt in 1924.

Contents

Why Did They Try Again?

After not succeeding in 1922 and 1924, the British waited eight years. Then, in August 1932, the 13th Dalai Lama gave them permission to try again. He said they could approach the mountain from the north side in Tibet. The only rule was that all climbers had to be British.

The British government and officials worked hard to get this permission. They were worried that German climbers, who had been exploring other big mountains, might try for Everest next.

Getting Ready for the Climb

Who Went on the Expedition?

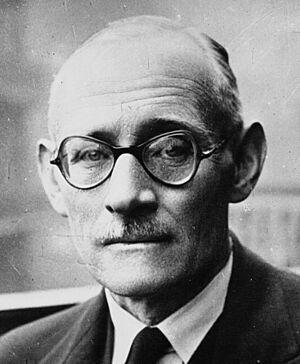

The Mount Everest Committee, which paid for all Everest attempts before World War II, had to pick a leader. The usual choice, General C. G. Bruce, wasn't available. Two other good choices, who had been on earlier Everest trips, said no. So, Hugh Ruttledge was chosen as the leader. He was 48 years old, and the rule was he shouldn't climb too high on the mountain himself. Many people were surprised by this choice, including Ruttledge. He was an experienced explorer of the Himalayas, but not a cutting-edge mountaineer. He also had a limp from an old accident.

Ruttledge was told to pick the British climbers. He wanted to invite climbers who had been to Everest before. Some couldn't make it, but E. O. Shebbeare, who handled transport in 1924, was chosen again. He also became the deputy leader. At 49, he was the oldest team member. Other climbers like Shipton, Dr Raymond Greene, and F. S. Smythe had climbed other high mountains.

Here are the sixteen British men who were part of the team:

| Name | Role | Job |

|---|---|---|

| Leader | Government worker | |

| Deputy leader and transport manager | Forestry Service | |

| Climber | Soldier | |

| Climber | Soldier | |

| Climber | University graduate | |

| Climber | Government worker | |

| Main doctor and climber | Doctor | |

| Climber | University lecturer | |

| Second doctor and climber | Mission staff | |

| Climber | Settler in Kenya | |

| Radio operator | Soldier | |

| Climber | Adventurer | |

| Radio operator | Soldier | |

| Climber | Geology lecturer | |

| Climber | Tea planter | |

| Climber | Government worker |

All climbers living in Britain had to pass physical and mental tests before joining.

Money and Gear

The Mount Everest Committee gave £5,000 for the trip. The total cost was expected to be much higher, around £11,000 to £13,000. They got more money from a book deal, a newspaper deal, and a gift from King George V. Many companies also gave equipment for free or at a discount.

They took five kinds of tents. Some were big mess tents, and others were smaller arctic tents that worked well in blizzards. They also had warm sleeping bags, including special double ones. For their feet, they had strong leather boots with special nails for climbing. They also had warm camp boots made of sheepskin. Special orange-tinted goggles protected their eyes from the sun and snow. Ice-axes and crampons (spikes for boots) came from Austria.

Just like on earlier trips, they brought extra oxygen. They planned to use it only above the North Col and only if someone needed it in an emergency. They had a lighter oxygen system that whistled to show it was working.

The Journey to Everest

The main group left England by ship on January 20, 1933. They stopped in places like Gibraltar and Aden. On the ship, they talked about how to climb Everest and set up camps. They also learned the Nepali language. They got off the ship in Bombay (now Mumbai), India. Ruttledge, who knew India well, took them sightseeing. They then went to Calcutta and finally to Darjeeling.

In Darjeeling, more climbers joined them. They also picked the porters (people who carry gear). Many of these porters were Sherpas, who are known for their strength in the mountains. Some had been on earlier Everest trips. All porters had health checks and were given special clothes and ID tags.

On March 2, the team had a special blessing ceremony in Darjeeling. Monks from a nearby monastery blessed everyone taking part in the expedition. Ruttledge said it was a very respectful ceremony.

They planned to take the shortest route to Everest, but it was too snowy. So, they took a longer way through the Chumbi Valley. The team split into groups for the first part of the journey. They traveled through many towns, meeting local officials. In Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim, they set up a postal service. They also got their passports with the Tibetan government's seal.

They crossed high passes like the Nathu La, where some climbers even climbed a smaller peak. They passed by the monastery at Khajuk, where the monks wondered why anyone would want to climb Everest. The whole team met up in Gautsa, where it got much colder and snowed for the first time.

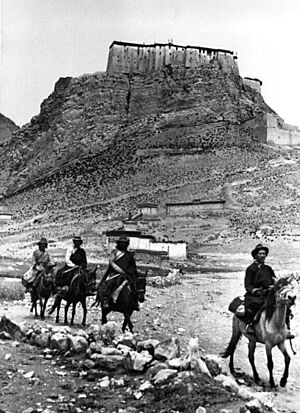

They continued their journey, passing through Phari Dzong and over several high passes. On March 29, they reached Kampa Dzong. From a pass above this town, they saw Mount Everest for the first time, about 100 miles away! At Kampa Dzong, Ruttledge dressed up in a special Tibetan gown and a top hat to meet the local leader. This helped them get along well. They also visited the grave of A. M. Kellas, an early climber who died on his way to Everest in 1921. They fixed his grave and held a small ceremony.

After Kampa Dzong, they went to Tengkye Dzong. Here, they played a football match, and one climber even did pole-vaulting with a bamboo pole! They continued their journey, facing challenges like a team member falling off his pony and needing urgent medical help.

They reached Shekar Dzong, a town with white houses and monasteries. Ruttledge called it "a setting for a fairy story." But they also had problems here, like a smallpox outbreak and some equipment being stolen. On April 13, they left Shekar, crossing the 17,000-foot Pang La pass.

On April 15, they reached Chö-Dzong. From a hill, they got a clear view of Mount Everest through a telescope. The north face looked mostly free of snow. The famous Second Step looked very difficult.

Ruttledge wrote about seeing the mountain up close:

"Darkness began to fall as long clouds drifted across the summit. We descended to camp in a mood of qualified optimism. At least we had been able, for the first time, to see for ourselves, to form a judgement of our own, and from a distance which allowed of a fairly true perspective. Henceforth we should be too much under the mountain to estimate our difficulties with any accuracy."

As they walked up the Rongbuk valley towards the Rongbuk Monastery, many Tibetans were leaving the monastery. The interpreter, Karma Paul, went to ask the lama (a Buddhist teacher) for a blessing. The lama blessed each team member, touching their heads and saying special words.

Setting Up the Camps

On April 17, they set up Base Camp. It was in the same spot as previous expeditions, about four miles from the Rongbuk Monastery. Some team members were sick here, so they went back down to Rongbuk. Despite this, everyone worked hard to set up the lower camps. The idea was to fully equip each camp before moving higher. This way, they could keep the camps supplied even in bad weather. The radio equipment was set up quickly, and they received a signal from Darjeeling.

They used local Tibetan workers to help carry supplies up to Camp II. This saved the high-altitude porters for higher up the mountain.

- Camp I was set up on April 21.

- Camp II was set up on April 26 at 19,800 feet (6035m). This camp was important for communication.

- Camp III was set up on May 2 at over 21,000 feet (6400m). From here, the North Col was clearly visible. The North Col was the first big climbing challenge. It had a steep ice wall that was always moving. They remembered that an avalanche killed seven porters in 1922, so they were very careful.

They found the route from 1924 too hard. So, they used the same route as in 1922. This led to a shelf below the North Col, where Camp IV would be. Between May 8 and 15, climbers like Smythe, Shipton, and Wager climbed the slope and set up fixed ropes. Every day, new snow would fill the steps they cut, making it hard to climb again. Smythe and Shipton made the final climb to the ledge on May 12. Bad weather stopped them from setting up Camp IV until May 15. After that, Camp IV was well-stocked.

Once they reached the North Col, they could set up higher camps. But there was a disagreement about where to put Camp V. On May 20, a group left their supplies on the slope and returned to Camp IV. Ruttledge went up to Camp IV to sort things out. He sent a team to set up Camp V at 25,700 feet on May 22. They passed a shredded tent from the 1922 attempt and found some old oxygen cylinders. One still worked!

Greene, who was supposed to go higher, had heart trouble and went down. Wager took his place. The next day, May 23, was cold and snowy. Shipton and Smythe went up to Camp V in strong winds. The radio line was extended to Camp IV, so news could reach London quickly. The bad weather continued, and the team higher up had to come down. Several Sherpas got frostbite, and one climber almost fell to his death.

Trying for the Summit

First Attempt: Wager and Wyn-Harris

Wager and Wyn-Harris left Camp VI at 5:40 a.m. on May 30 to try for the summit. Soon after starting, they found an ice-axe on the rocks below the north-east ridge. It had the name "Willisch of Täsch" on it. They left it there and picked it up on their way down. It's very likely this was Andrew Irvine's ice-axe from 1924.

Their first goal was to see if the Second Step on the ridge could be climbed. They went around the First Step and under the Second Step. They tried to find a gully (a narrow valley) that they thought would lead to the top of the Second Step. When that didn't work, they followed the path Norton took in 1924, along the slabs on the north face. They reached the Great Couloir at 10:00 a.m.

Second Attempt: Shipton and Smythe

Shipton and Smythe were waiting at Camp VI for Wager and Wyn-Harris to return. Shipton got sick and couldn't go on. After talking with Smythe, Shipton decided to go back down to Camp VI. Smythe continued alone. He reached 28,120 feet, about the same height as Wager and Wyn-Harris, before turning back.

What Happened Next?

The Mount Everest Committee looked into why the expedition failed. They decided that Ruttledge, though liked and respected, wasn't a strong enough leader.

One review of the expedition's book said it was "as fine as anything in Alpine literature." But it also pointed out three main reasons they didn't reach the top:

- Lost time: Disagreements about where to put Camp V led to losing a good climbing window between May 20 and 22. The weather got much worse after that. One climber said, "It may be that we lost not two days but twenty years."

- Wrong instructions: Wager and Wyn-Harris were told to try the Second Step, which wasted valuable time. Even when they took Norton's path, they weren't sure if the Step was unclimbable.

- Solo climb: Smythe had to try for the summit alone because Shipton got sick. Climbing alone, especially high on Everest in bad conditions, is very dangerous.

Shipton later wrote that the expedition was too big. He thought having fourteen climbers was too many. He believed that a large team made climbers feel less important. He suggested that future expeditions should have fewer climbers. Each person would then feel like a vital part of the team. Shipton's ideas were one reason he wasn't chosen to lead the successful 1953 expedition.

|

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |