Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652 facts for kids

| Act of Parliament | |

|

|

| Long title | An Act for the Setling of Ireland. |

|---|---|

Quick facts for kids Dates |

|

| Commencement | 12 August 1652 |

| Repealed | 1662 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Act of Settlement 1662 |

|

Status: Repealed

|

|

The Act for the Setling of Ireland was a law passed in 1652. It brought harsh punishments, including death and taking away land, for Irish people. This happened after a big uprising called the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and other troubles.

A historian named John Morrill said that this Act and the forced movement of people was "perhaps the greatest exercise in ethnic cleansing in early modern Europe." This means it was a huge effort to remove a group of people from their homes and lands.

Contents

Why Was This Act Created?

The English Parliament's Power

This law was passed on August 12, 1652, by the Rump Parliament in England. This Parliament had taken control after the Second English Civil War. They had also decided to conquer Ireland, which was known as the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.

Threats to the English Commonwealth

The English Parliament felt that conquering Ireland was necessary. Supporters of Charles II of England (the King) had joined forces with the Confederation of Kilkenny. This group was made up of Irish Catholics during the Irish Confederate Wars. Their alliance was seen as a threat to England's new government, the English Commonwealth.

Punishment for the Rebellion

Many members of the Rump Parliament felt strongly about the English settlers in the Ulster Plantation. These settlers had suffered a lot at the start of the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Stories of their suffering were made even bigger by Protestant messages. So, the Act was also a way to punish Irish Catholics who were seen as starting or continuing the war.

Paying for the Wars

Money to pay for the wars had been raised through a law from 1642 called the Adventurers' Act. This law promised to pay back lenders with land taken from the rebels of 1641. Many of these lenders had already sold their land rights to local landowners. These landowners wanted the new land transfers to be officially confirmed by a strong new law, just to be sure.

What Did the Act Say?

The Act started by saying that England had spent a lot of "Blood and Treasure" to stop the rebellion in Ireland. It claimed that with God's help, Ireland could soon be fully controlled and settled.

Who Was Punished?

The Act named ten leaders of the Royalist forces in Ireland. It also targeted anyone who had taken part in the early parts of the Irish Rebellion and had killed an Englishman outside of battle. These people would lose their lives and their property.

The Act also said that any Jesuit, priest, or other person who had received orders from the Pope or Rome, and who had helped the rebellion or war in Ireland, would also be punished. This included anyone who had helped with murders, massacres, or violence against Protestants or English people.

No Pardon for Some

The Act listed 104 men who would not be pardoned. This list included important people like nobles, landowners, army officers, and religious leaders. It had both Royalist supporters and those who supported the Confederation. The first ten people on this list were:

- James Butler, 12th Earl of Ormond

- James Touchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven

- Ulick Bourke, 5th Earl of Clanricarde

- Christopher Plunket, 2nd Earl of Fingal

- James Dillon, 3rd Earl of Roscommon

- Richard Nugent, 2nd Earl of Westmeath

- Murrough O'Brien, Baron of Inchiquin

- Donough MacCarty, 2nd Viscount Muskerry

- Theobald Taaffe, 1st Viscount Taaffe of Corren

- Richard Butler, 3rd Viscount Mountgarret

The Act treated people differently based on when they fought. Those who rebelled in 1641 were seen as unlawful combatants. But those who fought in the official armies of Confederate Ireland were treated as regular soldiers, as long as they gave up before the end of 1652. The 1641 rebels and the Royalist leaders mentioned above were not pardoned. They were to be executed if caught. Catholic religious leaders were also not pardoned. The English government believed they were responsible for stirring up the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

Loss of Land

The remaining leaders of the Irish army lost most of their land. This caused Catholic land ownership in Ireland to drop to only 8%. Even just being a bystander was seen as a crime. Anyone who lived in Ireland between October 1, 1649, and March 1, 1650, and had not clearly shown support for the English Commonwealth, lost three-quarters of their land.

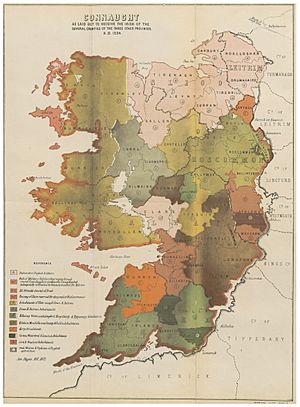

The English officials in Ireland could give these people other, poorer lands in Connacht or County Clare. They were also allowed to move people from their usual homes to other places in Ireland. This was done to keep the public safe.

Forced Movement of People

The English Parliamentarian leaders in Ireland ordered all Irish landowners to move to these new lands before May 1, 1654, or face execution. However, in reality, most Catholic landowners stayed on their land as tenants. The number of people actually moved or executed was small.

Protestant Royalists could avoid losing their land if they had surrendered by May 1650 and paid fines to the government. At first, the English government planned to remove Scottish Presbyterians from north-east Ulster. This was because they had fought with the Royalists later in the war. But this plan was changed in 1654. It was decided that the land confiscation would only apply to Catholics.

"To Hell or to Connaught"

In Irish history, people often remember the English government telling Catholic Irish people to go "to Hell or to Connaught." Connaught is a region in western Ireland, west of the River Shannon.

However, historian Padraig Lenihan says that the English did not actually say "To Hell or to Connaught." He explains that Connaught was chosen as a place for Irish people to live not because the land was poor. The English government actually thought Connaught was better than Ulster for this purpose. Lenihan suggests that County Clare was chosen for safety reasons. It would keep Catholic landowners trapped between the sea and the River Shannon. This forced movement of people, especially in Ulster, is often called an early example of ethnic cleansing.

Some Irish prisoners were even forced onto ships and sent to the West Indies. There, they became indentured servants on sugar cane farms owned by British colonists. One of the most famous islands where the Irish went after their work period ended was Montserrat.

In reality, a landowner and their family might lose their property and be given land in Connacht. They would then have to live there, usually as tenant farmers. For example, Thomas FitzGerald of Turlough's parents were moved from Gorteens Castle to land in Turlough, County Mayo. Most of the population, outside of the six counties that later became Northern Ireland, were expected to stay where they lived. They continued as tenant farmers or servants for the new landowners.

New Landowners

The Cromwellian Plantation

This Act led to the next stage of the Plantations of Ireland. The land that was taken was given to people called "Adventurers." These new owners were known as "planters." The Adventurers were people who had loaned the English Parliament a lot of money in 1642. They did this specifically to help stop the 1641 rebellion. The law allowing this had been signed by King Charles I just before the Wars of the Three Kingdoms began.

Many Protestants who lived in Ireland before the war also took advantage of the land confiscation. They bought land from the Adventurers to make their own land holdings bigger. Also, smaller pieces of land were given to 12,000 soldiers from the New Model Army who had served in Ireland. Much of this land was also resold. Decisions about which lands to take and which to give were based on maps and information from the Down Survey, made in 1655–56.

Confirming the Changes

In June 1657, another law, the Act of Settlement 1657, was passed. This law officially approved all the previous decisions, grants, and instructions made by officials and councils when they put the 1652 Act into action.

Changes After the King Returned

After the English Restoration, when the King returned to power, all laws passed during the English Civil War and the time without a king were considered invalid. This was because they had not received the King's official approval.

In 1662, a new law called the Act of Settlement 1662 was passed. This Act aimed to lessen the harsh effects of the 1652 Act on Protestants and "innocent Catholics." This new law gave some land back to important Irish Royalists. However, most of the land taken from Irish Catholics remained in Protestant hands.

See also

- Erasmus Smith