Africatown facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Africatown Historic District

|

|

Africatown welcome sign, 2017

|

|

| Location | Roughly bounded by Jakes Ln., Paper Mill & Warren Rds., Chin & Railroad Sts., in Mobile, Alabama |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 12000990 |

| Added to NRHP | December 4, 2012 |

Africatown, also known as AfricaTown USA, is a special community. It is located about three miles (5 km) north of downtown Mobile, Alabama. This historic place was started by a group of 32 West Africans. In 1860, they were brought to the United States against their will. This was the last known illegal shipment of slaves to the country.

The Atlantic slave trade had been banned since 1808. However, 110 enslaved people from the Kingdom of Dahomey were smuggled into Mobile. They arrived on a ship called the Clotilda. The ship was burned and sunk to hide this illegal act. More than 30 of these people, likely from the Yoruba, Ewe, and Fon groups, founded Africatown.

They kept their West African customs and language until the 1950s. Their children and some elders also learned English. Cudjo Kazoola Lewis, a founder of Africatown, lived until 1935. For a long time, he was thought to be the last survivor of the Clotilda living in Africatown.

In 2019, a researcher named Hannah Durkin found new information. She documented Redoshi, also known as Sally Smith. Redoshi was another West African woman from the Clotilda. She lived until 1937, making her the last known survivor at that time. Redoshi and her family lived in Dallas County, Alabama. Durkin later found that another survivor, Matilda McCrear, lived even longer, until 1940.

The number of people living in Africatown has gone down. It was once home to 12,000 people when paper mills were busy there. In the early 2000s, about 2,000 people lived there. Around 100 of them are descendants of the original Clotilda passengers. Many other descendants live across the country. In 2009, Africatown was named a site on Mobile's African American Heritage Trail. The Africatown Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012. Its cemetery, the Old Plateau Cemetery, started in 1876. It now has a large historical marker explaining its story.

Contents

Africatown's Story

Although the Atlantic slave trade was banned in the United States in 1807, some people still smuggled enslaved Africans. In 1860, some rich slaveholders in Mobile, Alabama, made a bet. They believed they could sneak a shipment of enslaved people into the country. They wanted to do this without being caught by federal agents.

Timothy Meaher, a ship owner, and others invested money. They hired a crew and a captain for Meaher's ship. Their goal was to go to Africa and buy people who had been enslaved by chiefs in Dahomey.

They used Timothy Meaher's ship, the Clotilda. This ship was usually used for carrying lumber. Captain William Foster was in charge. While the ship was in Whydah in the Kingdom of Dahomey (now Benin), changes were made. These changes helped hide the enslaved people. Foster bought 110 people and loaded them onto the ship.

The ship left Dahomey in May 1860 for Mobile. Foster had paid for 125 enslaved people. But he saw other ships offshore and left quickly to avoid them. The captives were mostly from the "Takpa" people. They were a group of Yoruba or Nupe people from what is now Nigeria. They had been captured by the King of Dahomey's forces. He sold them into slavery at the Whydah market. Captain Foster bought them for $100 each.

In July 1860, the Clotilda entered Mobile Bay. To avoid being caught, Foster had the ship towed upriver at night. He moved the enslaved people onto a riverboat and sent them ashore. Then, he set fire to the Clotilda and sunk it. This was to destroy evidence of the illegal smuggling. The Africans were mostly given to the people who had invested in the trip. They had to survive on their own at first. They built shelters and hunted for food in the Alabama lowlands.

Some of the enslaved people were sold to places far from Mobile. Redoshi, a woman from the Clotilda, and her husband were sold to Washington Smith. He owned a plantation in Dallas County, Alabama. Redoshi was known as Sally Smith. She and her family continued to work on the Smith plantation after they became free. Redoshi Smith was interviewed by writer Zora Neale Hurston. In 2019, researcher Hannah Durkin found that Redoshi Smith lived until 1937. This made her the last known survivor of the Clotilda at that time.

The Lawsuit Against the Smugglers

Federal authorities tried to put Meaher and his partners, including Foster, on trial. But they did not have the ship or other evidence. So, the 1861 court case, US v. Byrnes Meaher, Timothy Meaher and John Dabey, did not find enough proof to convict them. The case was dismissed. Historians believe the start of the American Civil War also caused the government to drop the case.

After the Civil War

Meaher first used 32 of the enslaved Africans as workers on his plantation. After the Civil War (1861–1865), they were freed. But they continued to work on Meaher's land north of Mobile. The former enslaved people started a community called Africatown. Water surrounded it on three sides: a bayou, Three Mile Creek, and the Mobile River.

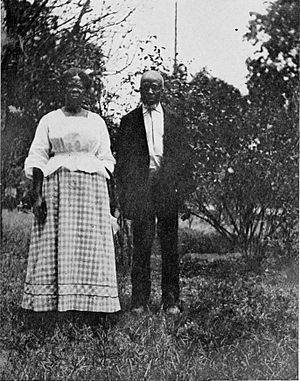

One of Africatown's founders was Cudjoe Kazoola Lewis. His Yoruba name was Kazoola or Kossola. He was said to be the oldest enslaved person on the Clotilda and a chief. Charlie Poteet was also called a chief. Their medicine man was named Jabez. Charles Lewis (whose Yoruba name was Oluale) and his future wife Maggie were also on the Clotilda. Cudjoe Lewis lived until 1935. Until 2019, he was thought to be the last survivor. He spoke for the community. Writers like Emma Langdon Roche and Zora Neale Hurston interviewed him. They used his stories to learn about the capture, the voyage, and the community.

After the Civil War, other people from the same African groups joined the Africatown community. They wanted to live independently and avoid white supervision. The community had two main parts. The first and larger part was about 50 acres. A second, smaller part was about 7 acres, two miles west. This area was called Lewis Quarters, named after founder Charlie Oluale Lewis and his wife Maggie.

Cudjo Lewis's son Joe learned to read and write at the church in Africatown. He helped keep the story of his father and the Clotilda alive. Families and schools also passed down these oral histories. The women grew and sold crops. The men worked in mills for $1 a day. They saved money to buy land from Meaher. They tried to avoid white people when possible.

They built the African Church, later called the Old Landmark Church. In 1876, they opened the Old Plateau Cemetery, also known as the Africatown Graveyard. In the early 1900s, they built a new brick church, the Union Missionary Baptist Church, which is still used today.

The community started its first public school in 1880. It is now known as the Mobile County Technical School.

Cudjoe Lewis helped his fellow Africans adjust to their new country. He spoke for the people of Africatown for many years. American writers Emma Langdon Roche and Zora Neale Hurston visited him. Educator Booker T. Washington also visited. Roche published a book in 1914 about American slavery and Africatown. In 1927, Hurston interviewed Cudjo Lewis. She later wrote a book about his life, which was published in 2018 as Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo".

During interviews, Lewis shared stories about civil wars in West Africa. People from the losing side were sold into slavery. His people, the Takpa, lived in an inland village. Cudjo told how warriors from Dahomey captured him and others. They were taken to Ouidah and held in a large slave compound. The King of Dahomey sold them to Foster. They were then brought to the U.S. on the Clotilda. After the Civil War, the people asked the U.S. government to send them back to Africa, but they were refused.

Africatown grew along Telegraph Road in the early 1900s. It became known as Plateau and Magazine. These areas later became part of Mobile and Prichard. Many company homes were built in Prichard for workers at shipyards and paper mills.

Changes After World War II

Africatown remained a separate community until World War II. Later, it became a neighborhood of Mobile. It was also known as Plateau.

A statue of Cudjo Lewis was placed in front of the Union Missionary Baptist Church in 1959. This honored his leadership. In 1977, a bronze plaque was given to the City of Mobile to remember Lewis. It was placed in Bienville Square downtown.

Africatown grew as new people arrived to work in the paper mills. The population reached 12,000. But it later declined when the big industries closed.

In 1997, descendants and friends started the AfricaTown Mobilization Project. They wanted Africatown to be a historic district. The Africatown Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 4, 2012.

In 2010, Neil Norman led an archaeological project in Africatown. He dug at the homesites of three Clotilda survivors: Peter Lee, Cudjo Kazoola Lewis, and Charlie Lewis. They found some items that might have come from Africa. In 2012, the historic district was cleaned up. The cemetery was also cleaned and restored. A large historical marker was placed outside the cemetery.

Around 2,000 people live in Africatown today. About 100 of them are known descendants of Clotilda survivors. Ahmir Khalib Thompson, also known as Questlove, is a famous drummer and music producer. He is a great-great-great grandson of Charles Lewis and his wife Maggie, who were both from Africa.

Africatown Historic District

Most of Africatown is now within Mobile's city limits. Its people passed down the story of its founders. They preserved their history through families, the church, and schools.

Some of the community's land was used for the Cochrane-Africatown USA Bridge. This bridge was finished in 1992. In 1997, descendants and friends formed the Africatown Community Mobilization Project. They wanted the Africatown Historic District to be recognized. They also wanted to help restore and develop the town. In 2000, they sent information about their project to the Library of Congress. This included text, photos, a map, newspaper articles, and a video.

The historic district is roughly bounded by Jakes Lane, Paper Mill and Warren roads, and Chin and Railroad streets. In 2009, it was named a site on Mobile's African American Heritage Trail. The Africatown Historic District was then recognized by the state and the National Park Service. It was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 4, 2012.

Environmental Concerns

Because of its location near waterways, Africatown became home to mills and other industries. A paper plant was built in 1928 and operated for many years. Residents have expressed concerns about health issues in the community. They believe these issues are related to past industrial activities.

In 2017, a group of about 1,200 residents filed a lawsuit against International Paper (IP). This company had owned the paper plant, which is now closed. The group claims that the company's handling of waste over the years harmed the land and water. They also say the company did not clean up the site properly after closing the plant.

Discovery of the Clotilda Wreck

In January 2018, reporter Ben Raines found the burnt remains of a ship. He thought it might be the Clotilda. On March 5, 2018, Raines announced that the wreck he found was probably not the Clotilda. It seemed too big.

A few weeks later, Ben Raines and a team from the University of Southern Mississippi returned. They explored the 12 Mile Island section of the Mobile River. On April 13, the team found the first piece of the Clotilda seen in 160 years. The information was shared with the Alabama Historical Commission. They hired Search Inc. to confirm the find. The discovery was kept secret for a year. On May 22, 2019, the Alabama Historical Commission announced that the wreck of the Clotilda had been found. It was in the Mobile River near Africatown.

Africatown in Media

- In 2020, author Beth Duke wrote a novel called Tapestry. It features Africatown and won an award.

- A local Mobile TV news program made a show called "AfricaTown, USA" about the community.

- In Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s show Finding Your Roots, he explored the family history of Questlove. Questlove is a drummer and producer. His great-great-great grandparents, Charles Lewis and Maggie, were among the captives on the Clotilda.

- Natalie S. Robertson wrote a book, The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of AfricaTown, U.S.A.. It explains where the Clotilda Africans came from in West Africa.

- Zora Neale Hurston's book Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo" was published in May 2018. It tells Cudjo Lewis's story.

- The podcast On The Media interviewed Africatown residents and historians.

- The Extinction Tapes, a 2019 documentary, discussed how the discovery of the Clotilda wreck was linked to pollution. It suggested that the decline of a river mussel, the Alabama pigtoe, was a warning sign for Africatown's health.

- Descendant, a 2022 Netflix documentary, tells the story of activists in Africatown. They are working to reclaim their history.

See Also

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |