Agriculture in Scotland in the Middle Ages facts for kids

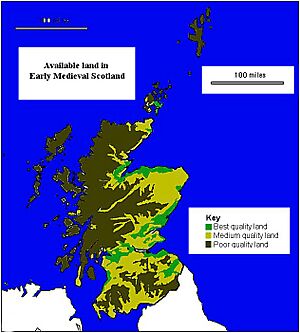

Agriculture in Scotland in the Middle Ages covers how people farmed in what is now Scotland, from when the Romans left Britain in the 400s until the Renaissance began in the early 1500s. Scotland has much less good farming land than England and Wales, mostly in the south and east. Heavy rain caused a lot of acidic peat bog (wet, spongy ground), and strong winds and salt spray made most western islands treeless. Hills, mountains, and marshes made farming and travel difficult. Most farms had to grow enough food for themselves, including meat, dairy, and grains. People also found food by hunter-gathering. The early Middle Ages saw a colder, wetter climate, making some land unusable. Farms were usually a single home or a small group of three or four homes. Each likely held a nuclear family (parents and children). Cattle were the most important farm animals.

From 1150 to 1300, warmer, drier summers and milder winters allowed farming in higher places and made land more productive. Crop farming grew a lot, but it was still more common in low areas than in the Highlands, Galloway, and the Southern Uplands. A farming system called infield and outfield, a type of open-field farming, might have started with feudalism around the 1100s. Crops included bere (a type of barley), oats, and sometimes wheat, rye, and legumes (like peas or beans). Hunting areas were set up by powerful lords. New religious groups, like the Cistercians, became big landowners and sheep farmers, especially in the Borders region. They organized their farms into granges.

By the late Middle Ages, most farming happened in settlements called fermtouns in the Lowlands or bailes in the Highlands. These were small groups of families who farmed an area together. This land was divided into run rigs for tenant farmers, known as husbandmen. Runrigs usually went downhill to include both wet and dry land. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron blade, pulled by oxen. Oxen were better and cheaper to feed than horses. Important crops included kale, hemp, and flax. Sheep and goats likely provided most of the milk, while cattle were raised for meat. The farming economy seemed to do well in the 1200s and right after the Black Death (a terrible plague) in 1349. However, by the 1360s, incomes dropped sharply, followed by a slow recovery in the 1400s.

Contents

Early Farming Life (5th to 10th Century)

Scotland is about half the size of England and Wales. It has a similar amount of coastline but much less good farming land, especially land below 60 meters (about 200 feet) above sea level. Most of this good land is in the south and east. This meant that raising animals on less fertile land and fishing were very important for the economy back then.

Scotland's location means it gets moderate rainfall. Today, it's about 700 mm (27 inches) per year in the east and over 1,000 mm (39 inches) in the west. This rain helped peat bogs spread. The acidic soil of these bogs, along with strong winds and salt spray, meant most western islands had no trees. Hills, mountains, and marshes made farming and travel difficult.

The early Middle Ages (from the 400s to the 900s) saw a colder climate with more rain. This made more land unproductive. Since there weren't good transport links or big markets, most farms had to produce all their own food. This included meat, dairy products, and grains, plus food gathered from hunting. Limited archaeological finds show that farming was based around a single home or a small group of three or four homes. Each home likely had a nuclear family. Family ties were probably strong among nearby houses and settlements.

Because of the climate, people grew more oats and barley than wheat. Bones found from this time show that cattle were by far the most important farm animal. Pigs, sheep, and goats were also raised, but domesticated birds were rare. Christian missionaries from Ireland might have brought new farming ideas. These included the horizontal watermill (a mill powered by water) and mould board ploughs, which were better at turning the soil.

Farming in the High Middle Ages (1150-1300)

From 1150 to 1300, Scotland experienced the Medieval Warm Period. This meant warm, dry summers and milder winters. This climate allowed farmers to grow crops at much higher elevations and made the land more productive. Crop farming grew a lot, but it was still more common in low-lying areas in the south and east. High-lying areas like the Highlands, Galloway, and the Southern Uplands had less crop farming.

The system of feudalism was introduced under King David I. This was especially true in the east and south, where the king had the most power. Under feudalism, powerful lords were given land by the king. In return, they promised loyalty and military service. These lords could hold courts to deal with land ownership issues. However, the old ways of owning land still existed alongside feudalism. It's not fully clear how these changes affected the lives of ordinary free and unfree workers. In some places, feudalism might have tied workers more closely to the land. But because Scottish farming was mostly about raising animals, the English-style manorial system (where a lord controlled a large estate) might not have worked everywhere. Farmers' duties often included providing oxen for ploughing the lord's land and grinding their grain at the lord's mill, which people often disliked.

Powerful lords, first Anglo-Norman and then Gaelic, created hunting reserves. These were large areas set aside for the nobility to hunt. These reserves were not as strict as in England. Taking wood or game was not as strictly forbidden.

New religious groups, like the Cistercians, also brought new farming methods. Especially in the Borders region, their monasteries became major landowners. They raised many sheep and produced wool for markets in Flanders (a region in modern-day Belgium). These farms were called granges. They were run by lay brothers (monks who did manual labor). Granges were usually within 30 miles of the main monastery so workers could attend church services. They were used for various purposes, including raising animals, growing crops, and even industrial production. Some abbeys, like Melrose, had at least 12,000 sheep in the late 1200s!

The system of infield and outfield farming, a type of open field farming used across Europe, might have started with feudalism. This system continued until the 1700s. It grew from the use of small enclosed fields that had been around since prehistoric times.

- The infield was the best land, close to the homes. It was farmed constantly and very intensely, getting most of the animal manure (fertilizer). Crops usually included bere (a type of barley), oats, and sometimes wheat, rye, and legumes.

- The more spread-out outfield was mainly used for oats. It was fertilized by keeping cattle there overnight in the summer. It was often left unplanted to regain its richness. In fertile areas, the infield could be large, but in the uplands, it might be small with a lot of outfield around it. Near the coast, seaweed was used as fertilizer, and around big towns, city waste was used.

Crop yields (how much crop you get from the seeds you plant) were fairly low. Often, farmers got about three times the amount of seed they planted. However, on some infields, they could get twice that amount.

Later Medieval Farming (14th to 15th Century)

By the 1300s, most farming was based in settlements called fermtouns in the Lowlands or bailes in the Highlands. These were small groups of families who farmed an area together. This land was divided into run rigs for tenant farmers, who were usually called husbandmen. An average husbandman in Scotland farmed about 26 acres. They also shared hay meadows and common grazing land. Below the husbandmen were the cottars. Cottars often shared rights to common grazing, had small plots of land, and helped with joint farming as hired workers. Some farms also had "grassmen," who only had rights to graze animals.

Grazing land was often accessed through shieling-grounds. These were areas with simple shelters made of stone or turf, used for grazing cattle in summer. In the Lowlands, these shieling-grounds were often far from the main settlements. In the more remote Highlands, they might be closer.

Runrigs were a pattern of alternating "runs" (furrows) and "rigs" (ridges) in the fields. They were similar to patterns used in parts of England. Runrigs usually ran downhill. This meant they included both wet and dry land, which helped deal with extreme weather. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron blade. These ploughs were pulled by oxen, which were better on heavy soils and cheaper to feed than horses. A team of eight oxen usually pulled the plough, needing four men to operate it. They could only plough about half an acre a day.

Important crops included kale (for both people and animals), and hemp and flax for making cloth. Sheep and goats were probably the main sources of milk, while cattle were raised mostly for meat. The rural economy seemed to do very well in the 1200s. Even right after the Black Death, which arrived in Scotland in 1349 and might have killed a third of the population, the economy was still strong. However, by the 1360s, incomes dropped sharply, by about a third to half. This was followed by a slow recovery in the 1400s. Towards the end of this period, average temperatures started to drop again. The colder, wetter conditions of the Little Ice Age limited how much land could be used for growing crops, especially in the Highlands.

See Also