Antonio de Vea expedition facts for kids

The Antonio de Vea expedition of 1675–1676 was a big trip by the Spanish navy. They explored the fjords and channels of Patagonia in South America. Their main goal was to find out if other European countries, especially England, had set up secret bases there.

This was not the first Spanish trip to this area, but it was the biggest one yet. It included 256 men, one large ship, two long boats, and nine dalcas. Dalcas were special canoes used by local people. The expedition found no English bases in Patagonia. This trip greatly improved what the Spanish knew about western Patagonia. However, after this, Spain's interest in the area decreased until the 1740s.

Contents

Why the Expedition Happened

The idea for this expedition came from the explorations of John Narborough. He had explored the coasts of southern Patagonia a few years earlier. Spain heard about his trips from different sources.

First, the Spanish ambassador in England learned about it. Then, Spanish soldiers captured some of Narborough's crew in 1670. People in Chiloé, a Spanish area, also heard rumors from local native groups.

In 1674, the governor of Chiloé sent a small trip south. It was led by Jerónimo Díaz de Mendoza. He returned with a native Chono man named Cristóbal Talcapillán. Talcapillán lived in Chacao, Chiloé, and quickly learned some of the local Veliche language.

Talcapillán started telling stories about Europeans in the far south. He gave detailed accounts of English settlements on two Patagonian islands. This worried the Spanish leaders a lot. They asked Talcapillán to draw a map of the islands. When they checked his map with Spanish sailors, they were amazed. This made them believe his stories even more.

Talcapillán said the English, whom he called "Moors," had two settlements. One was on the mainland called Callanac, and another on an island called Allauta. He claimed the English were building a fort at Callanac with help from local natives. Talcapillán also mentioned an Indian named León who had traveled to England. He also spoke of a Spanish shipwreck on Lluctui island, which he said the English controlled.

The Journey Begins

Getting Ready and Traveling to Chiloé

Antonio de Vea was chosen to lead and organize the expedition. He was in Portobelo, Panama, when he received the order. The expedition got ready in the port of El Callao, Peru. They set sail for Chiloé on September 21, 1675.

De Vea sailed on a ship called Nuestra Señora del Rosario y Ánimas del Purgatorio. He brought materials to build two extra "long boats" in Chiloé. In Chiloé, the expedition was to split into two groups. One group, led by Antonio de Vea, would sail south along the coast. The other group, led by Pascual de Iriarte, would go directly to the Straits of Magellan by open ocean. Both groups planned to meet there.

On October 13, the expedition saw the empty Alejandro Selkirk Island. They did not land there. De Vea wrote that a sailor died on October 29. On October 30, they saw Lacuy Peninsula and the nearby mainland. As they entered Chacao Channel, their ship hit a rock called Roca Remolino. The ship was badly damaged. Two Spanish dalcas quickly rescued the soldiers. Antonio de Vea and the rest of the crew managed to get the ship to the beach that evening.

Exploring Guaitecas and San Rafael Lake

On November 28, the expedition left the shipyard in Chiloé. By then, nine dalcas had been added to the two long boats. Antonio de Vea's group was guided by Bartolomé Gallardo, a local soldier. A Jesuit priest named Antonio de Amparán and Cristóbal Talcapillán also joined them.

De Vea's group had 70 Spaniards, including 16 sailors, and 60 native people. All the Spaniards were from Chile and Peru. As they sailed south, they saw forests of Pilgerodendron trees. De Vea said they looked like the "cypresses of Spain." During their journey, they also caught "over 200 basses" using fishing nets.

On December 11, the expedition entered San Rafael Lake. They noticed it was very windy. They also saw the San Rafael Glacier and the swampy shores to the south. These swamps make up the Isthmus of Ofqui. Antonio de Vea entered the lake through Río Témpanos (meaning "Ice Floe River"). He did not mention any ice floating in the river. He also said the San Rafael Glacier did not reach far into the lake. This suggests that the effects of the Little Ice Age were not strong there in the late 1600s.

Beyond the Isthmus of Ofqui

At the southern part of San Rafael Lake, the expedition split into two groups. One group stayed behind to wait. The other group went further south, crossing the isthmus of Ofqui by land. This group had 40 Spaniards and 40 native people. Antonio de Vea led them, and Talcapillán and Bartolomé Gallardo were with him.

De Vea's group used four dalcas. They took the dalcas apart and carried them across part of the isthmus. Then they put them back together. The ground was very swampy, so this was a lot of hard work, even though the distance was short. On December 23, they reached the mouth of the San Tadeo River by the sea. They caught more than 100 basses there. Rain stopped them on December 24. But on Christmas Day, December 25, they reached San Javier Island. Antonio de Vea called it San Esteban Island.

On December 25 and 26, the expedition captured several native Chono people on San Javier Island. This included children and an old woman. The woman, who de Vea thought was about 70 years old, told the Spanish about fights with another native group called Caucagues. She said the Caucagues had iron from anchors of European ships.

Talcapillán helped with the questioning, translating from Chono to Veliche. Then another man, Lázaro Gomez, translated from Veliche to Spanish. The woman said the Caucagues knew the Spanish were coming. An Indian who escaped from Calbuco in Chiloé had warned them, so they were hiding. When asked about the shipwreck where the anchor came from, the woman said it happened when she was very young. On January 2, 1676, the expedition found a whale carcass and an empty Caucague camp with many dogs. The Caucagues were thought to have run away inland.

Antonio de Vea later decided that Talcapillán was not a good interpreter. The old woman said she had never mentioned iron anchors. Talcapillán then admitted he had lied about the anchors. He said Bartolomé Gallardo and his father had forced him to lie.

Before heading back north, the expedition left a bronze plaque on San Javier Island. It said that the King of Spain owned the area. On the way back, they reached Guaiteca Island on January 22. They returned to the shipyard in Chiloé four days later. Antonio de Vea claimed to have reached as far south as 49°19' S, but this might have been an overestimation.

Pascual de Iriarte's Group

When Antonio de Vea sailed south, Pascual de Iriarte's group was supposed to follow soon. They waited for repairs to their ship, Nuestra Señora del Rosario y Ánimas del Purgatorio, to finish. But the repairs took too long. So, they found another ship to sail south into the open sea.

On February 17, sixteen men from Iriarte's group died near the Evangelistas Islets. This included Pascual de Iriarte's son. The accident happened when a small boat went to the islets to place a metal plaque. This plaque would show that the King of Spain owned the land. Strong winds hit the boat, and it drifted away. The rest of the expedition could not find the lost men. Bad weather forced them to return north without searching more. This group had reached about latitude 52°30' before turning back.

The survivors of Pascual de Iriarte's group arrived at the fort of Carelmapu near Chacao on March 6. Their ship was in bad shape, and the crew was very thirsty.

What Happened After

The expedition returned to El Callao, Peru, in April 1676. While they were away, 8,433 men had been prepared in Peru to fight if England attacked. The military in Peru also received large donations for defense costs.

The Viceroy of Peru, Baltasar de la Cueva, ordered officials in Chile, Chiloé, and Río de la Plata to look for the men lost at Evangelistas Islets. But no information about them was found. It is believed their boat wrecked in the same storm that forced the other group to leave. In total, 16 or 17 men died.

Antonio de Vea successfully convinced Spanish leaders that the rumors about English settlements in Patagonia were false. He noted that while there were many shellfish, sea lions, and whales, it was not possible for Europeans to settle there. The bad weather and poor soil made it impossible to grow crops.

However, in 1676, new rumors from Europe reached the Spanish court. It was claimed that England was planning to settle the Straits of Magellan. So, Spain's focus shifted. They started worrying about English settlements in the Straits of Magellan and Tierra del Fuego instead of western Patagonia. This was because any English settlement there could be reached by land from the north. This was not true for the islands in western Patagonia.

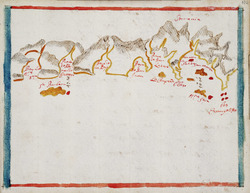

Even though it had some problems, the Antonio de Vea expedition greatly increased Spain's knowledge of the Patagonian islands. The map Antonio de Vea made of the area was a very important step in local map-making. As far as we know, no new Spanish maps of western Patagonia were made until José de Moraleda y Montero explored the area in the late 1700s.

After this expedition, there was a long break of several decades. During this time, there was less missionary work and less searching for foreign colonies on the Pacific coast of Patagonia. Interest in the area grew again in the 1740s. This happened when the Spanish learned about the shipwreck of HMS Wager on Wager Island in the Guayaneco Archipelago.

See Also

In Spanish: Expedición de Antonio de Vea para niños

In Spanish: Expedición de Antonio de Vea para niños

- City of the Caesars

- Coastal defence of colonial Chile

- Nicolás Mascardi