Battle of Cooch's Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Cooch's Bridge |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

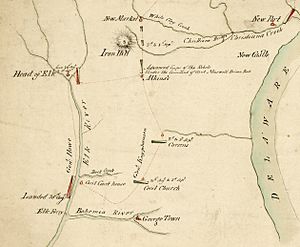

Detail of a 1777 military map. Cooch's Bridge is just to the right of Iron Hill; Philadelphia is off to the northeast. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,000 | 450 jägers 1,300 British light infantry |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20 killed 20 wounded |

23 to 30 killed or wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Cooch's Bridge, also known as the Battle of Iron Hill, was a fight during the American Revolutionary War. It happened on September 3, 1777. American soldiers and local fighters faced off against British troops and their German allies, called Hessians.

This battle was the only major land fight of the war in Delaware. It took place about a week before the bigger Battle of Brandywine. Some stories say this was the first battle where the American flag was flown.

British and German forces landed in Maryland on August 25, 1777. They were part of a plan to capture Philadelphia, which was then the capital of the American colonies. As they moved north, American soldiers watched them closely. These American troops were based near Cooch's Bridge, close to Newark, Delaware.

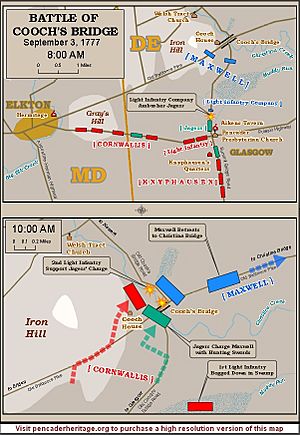

On September 3, German soldiers leading the British advance were surprised. American light infantry fired at them from the woods. The Germans called for help and pushed the Americans back. The Americans were forced to retreat across Cooch's Bridge.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After taking New York City in 1776, the British had a plan. They wanted to divide the Thirteen Colonies and end the war quickly. One part of their plan was to control the Hudson River. The other part was to capture Philadelphia, the American capital.

In July 1777, British General William Howe sailed from New York City. He had about 18,000 soldiers with him. They sailed to the Chesapeake Bay. General George Washington and his Continental Army of about 16,000 men were watching. When Howe's goal became clear, Washington marched his army through Philadelphia. They set up camp in Wilmington, Delaware.

British and American Movements

On August 25, Howe's army landed in Elkton, Maryland. This town was about 50 miles (80 km) south of Philadelphia. The landing spot was not very good. So, the troops quickly moved north to Elkton by August 28.

Advance troops, including British light infantry and German Jäger (hunters), moved east. They crossed Elk Creek and took over Gray's Hill. This hill was near Iron Hill and Cooch's Bridge. The bridge was named after Thomas Cooch, a local landowner.

Washington usually sent Daniel Morgan and his riflemen for advance guard duties. But they were helping another general, Horatio Gates, in the north. So, Washington created a new light infantry group. It had 700 chosen men from the Continental Army and about 1,000 local fighters. He put Brigadier General William Maxwell in charge.

Maxwell's troops took positions at Iron Hill and Cooch's Bridge. General Nathanael Greene thought the whole army should move there. But Washington disagreed. He told Maxwell to watch the British and slow them down. The rest of Washington's army built defenses near Red Clay Creek and Wilmington.

Maxwell's men set up small camps along the road. These camps were designed to ambush the British. On August 28, Washington and Howe watched each other from their hills. One German general wrote that they observed each other very carefully.

The Armies Advance

On September 2, Howe's right side of the army moved north. This group was led by German General Wilhelm von Knyphausen. Rain and bad roads made their march difficult.

Early on September 3, Howe's left side of the army left Elkton. This group was led by Charles Cornwallis. They planned to meet Knyphausen's group at Aiken's Tavern. Cornwallis got there first. Howe, who was with Cornwallis, decided to keep moving north without waiting for Knyphausen.

The Battle Begins

A small group of German horsemen, called Hessian dragoons, rode ahead. They were led by Captain Johann Ewald. As they went up the road toward Cooch's Bridge, American soldiers ambushed them. Many German soldiers were killed or hurt.

Captain Ewald was not hurt. He quickly warned the German and Ansbach Jäger (light infantry). These soldiers rushed forward to fight the Americans. This started a running gunfight. A British officer, Major John André, wrote that the Americans attacked with "a continued irregular fire for nearly two miles."

General Howe rode to the front lines. He saw Iron Hill covered with enemy soldiers. He ordered his troops to clear the hill. At this time, many of Maxwell's American forces were defending Iron Hill. Others were protecting Cooch's Bridge.

Fighting at Iron Hill and the Bridge

The Jäger, more than 400 men, formed a line. They were led by Lieutenant Colonel Ludwig von Wurmb. With some cannon support, they moved toward the Americans. Von Wurmb sent some soldiers to Maxwell's left side. He hoped to attack them from the side. He also ordered a bayonet charge against the American center.

The battle lasted for most of the day. At Cooch's Bridge, Maxwell's men fought until they ran out of ammunition. They then fought with swords and bayonets. Maxwell's local fighters were not used to fighting with bayonets.

After seven hours of fighting, the Americans had to retreat. They moved from Iron Hill across Cooch's Bridge. They took a new position on the other side of the bridge. Howe ordered the British Light Infantry to help the Jäger take the bridge. One British group got stuck in a swamp. But the other group reached the Jäger, and the bridge was taken. Maxwell's army then retreated toward Wilmington.

Reports on how many British soldiers were hurt vary. Some say 3 killed and 20 wounded. Others say about 30 killed or wounded. One British soldier who left the army said nine wagons of wounded were sent away. The Americans said 20 were killed and 20 wounded. Washington wrote that their losses were "not very considerable." However, the British reported burying 41 Americans. Howe's official report claimed "not less than fifty killed and many more wounded." Some officers criticized General Maxwell's leadership.

What Happened Next

After the battle, General Cornwallis stayed at Thomas Cooch's house. Howe's forces remained at Iron Hill for five days. Washington explained the American defeat to Congress. He said the enemy had more soldiers and cannons. He noted that his light troops were forced to retreat after a "pretty smart skirmishing."

Washington believed Howe would advance toward Wilmington to capture Philadelphia. So, he kept building defenses for the city and near Red Clay Creek. He moved his headquarters to Newport. His army set up defenses between Newport and Marshallton.

For the next few days, the two armies had small fights. A British officer noted that American patrols were appearing more often. They would fire at British posts.

Washington's Words

On September 5, Washington told his troops that if the British attacked Philadelphia, it would be a huge risk for them. He said, "If they are overthrown, they are utterly undone—the war is at an end." Two days later, Washington heard that British ships had left the Chesapeake Bay. He was sure Howe's attack was coming soon.

He encouraged his troops. He mentioned the American successes against the British in the north. He said, "Who can forbear to emulate their noble spirit? Who is there without ambition, to share with them, the applauses of their countrymen, and of all posterity, as the defenders of Liberty, and the procurers of peace and happiness to millions in the present and future generations?" He added, "Two years we have maintained the war and struggled with difficulties innumerable. But the prospect has since brightened... Now is the time to reap the fruits of all our toils and dangers! ... The eyes of all America, and of Europe are turned upon us."

Moving to Brandywine

But the attack on Wilmington never came. Instead, on September 8, Howe moved his army north. They went through Newark and Hockessin into Pennsylvania. Washington realized what the British were doing late that night. He quickly moved his forces north too, looking for a new place to defend.

He chose Chadds Ford, just across the Delaware border. This spot was on the Brandywine River. It was the last natural defense before the Schuylkill River and Philadelphia. The two armies fought there again in the big Battle of Brandywine on September 11. The British won that battle. This victory allowed them to enter and take over Philadelphia.

However, the British success in Philadelphia was balanced by a big loss in the north. General Burgoyne's army surrendered after the Battles of Saratoga in October. News of Burgoyne's surrender changed the war. It helped convince France to join the war as an American ally in 1778.

Battlefield Today

The area where the battle happened is now a protected historic place. It is called the Cooch's Bridge Historic District. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2003, the Cooch family sold some land to the state. They also sold the right to develop another 200 acres (81 hectares) of land. They set up a $1.5 million fund to help take care of the property. The family also gave the state the first chance to buy the Thomas Cooch house.

In 2007, people held a re-enactment event to remember the battle's 230th anniversary.

The Battle of Cooch's Bridge is shown on the coat of arms for Glasgow High School. The school is built on part of the battlefield. It shows American soldiers fighting British soldiers. They are flying the "Betsy Ross flag". In 2010, the Christina School District Honor Band played a song named "The Battle of Cooch's Bridge March."

In late 2018, the state of Delaware announced it would buy the historic house and some land. The state paid $875,000, and private groups added $225,000. The goal is to use the site to teach people about the battle. The state also wants archaeologists to dig there. They hope to find unmarked graves of those who fought. The Cooch family promised to donate 20% of the sale money to a fund that helps preserve the site.

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |