Battle of the Little Bighorn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of the Little Bighorn |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Sioux War of 1876 | |||||||

The Custer Fight by Charles Marion Russell |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Irregular military | 7th Cavalry Regiment | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500–2,500 warriors | ~700 cavalrymen and scouts | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| 10 Non-combatant natives killed | |||||||

The Battle of Little Bighorn is a famous fight from American history. It happened on June 25–26, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in what is now Montana. The battle was between the United States Army and several Native American tribes. These tribes included the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho.

Native Americans call this battle the Battle of the Greasy Grass. Americans often call it Custer's Last Stand. The Native American forces were led by strong war leaders like Crazy Horse and Chief Gall. Before the battle, Sitting Bull had a vision that showed the Native Americans would win.

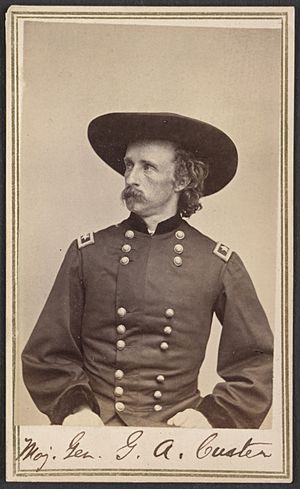

The U.S. Army's 7th Cavalry Regiment had about 700 soldiers. They were led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. The Native American tribes fought bravely and won a big victory. Custer and many of his soldiers were killed. This included two of his brothers, a nephew, and a brother-in-law.

In total, 268 U.S. soldiers died, and 55 were wounded. The battle is remembered today at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. This monument honors everyone who fought there.

Contents

Why Did the Battle of Little Bighorn Happen?

In 1868, many Native American leaders signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie. This treaty set aside land in South Dakota, including the Black Hills, for the Native American tribes. This area was called the "Great Sioux Reserve." It was meant to keep white settlers and Native American tribes separate.

However, gold was found in the Black Hills. The U.S. government tried to buy the land, but the Native Americans refused. The land was sacred to them. The government then decided to call the tribes "hostile" and sent soldiers to force them out of the Black Hills.

The U.S. military planned a large attack. Three groups of soldiers were sent to find the Native American tribes. One group, led by Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry, marched west. Lt. Col. Custer led the largest part of Terry's troops. They arrived near the Little Bighorn River on June 24, 1876.

Major Reno's Attack

Custer's Crow Indian scouts warned him that a very large Native American camp was nearby. Even with this warning, Custer decided to attack on June 25. He split his soldiers into four groups. He believed the Native Americans would run away when they saw the soldiers.

The first group to attack was led by Major Marcus Reno. His soldiers shot at the Native Americans from far away. Reno soon realized his men would be killed if they moved closer. Custer had promised to support Reno, but he did not send any help.

Reno and his troops had to retreat to nearby woods. They then moved up the river to some high ground called bluffs. The Native Americans followed them, and many of Reno's men were killed during this retreat.

Custer's Final Fight

While Reno was fighting, Custer rode along the bluffs. He then went down into a valley called Medicine Tail Coulee, which led to the river. It's not fully clear if Custer attacked first or if the Native Americans attacked him. However, a fierce battle began.

The Native Americans who had been fighting Reno's group joined the fight against Custer. Custer and his men were greatly outnumbered. Within two to three hours, Custer and all his soldiers were killed. Stories say that Crazy Horse personally led one of the large groups of Lakota warriors who defeated the cavalrymen.

What Happened After the Battle?

After defeating Custer, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne returned to attack the remaining soldiers under Benteen and Reno. However, more U.S. forces under Terry were approaching from the north. The Native Americans then moved south.

Custer's body was found at the top of a hill. A large stone monument, called an obelisk, now stands there. He had been shot in the head and chest. Some Native American stories say Custer took his own life to avoid being captured.

A few days after the battle, a young Crow scout named Curley shared what he saw. He said Custer had attacked the village after crossing the river. Custer was then forced back across the river and up the hill where he died. This story matched how Custer usually fought and the evidence found on the ground.

Of the U.S. soldiers, 210 died with Custer. Another 52 died fighting under Reno. Six more men died later from their wounds. Several of Custer's family members also died, including his younger brothers Boston and Thomas. A newspaper reporter named Mark Kellogg, who was with Custer, also died. It is thought that up to 200 Native Americans might have died.

News of Custer's Last Stand made many Americans angry. The government then worked harder to force Native Americans onto reservations. Soon after, the government broke the Treaty of Fort Laramie and took back the Black Hills.

How is the Battlefield Preserved Today?

The battle site was first protected as a national cemetery in 1879. This was to protect the graves of the 7th Cavalry soldiers. It was later renamed Custer Battlefield National Monument in 1946. In 1991, it was renamed Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument.

A temporary monument was built in 1879. This was replaced by the current marble obelisk in 1881. In 1890, small marble markers were added across the field. These markers show where U.S. cavalry soldiers died.

The law that changed the monument's name also called for an Indian Memorial. This memorial was built near Last Stand Hill. In 1999, two red granite markers were added where Native American warriors fell. By 2005, there were 10 warrior markers on the battlefield.

Interesting Facts About the Battle

- Custer brought his dogs with him to Little Bighorn.

- This battle was the worst defeat for the U.S. Army during the American Indian Wars.

- About 3,000 Lakota and Cheyenne warriors were camped near the Rosebud Creek.

- The main part of the battle lasted about two hours.

- The army's rifles were not very effective because the fighting was very close.

- 268 U.S. soldiers died in the battle.

- Custer was found lying next to a horse when his body was discovered.

- The Lakota called it the “Battle of the Greasy Grass” because of how the grass looked near the water.

- Frank Finkel claimed he was the only survivor of "Custer's Last Stand."

- Archaeologists and historians are still studying items found on the battlefield.

Other pages

Images for kids

-

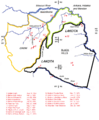

Map indicating the battlefields of the Lakota wars (1854–1890) and the Lakota Indian territory as described in the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851).

-

7th Cavalry Regiment Troop "I" guidon recovered at the camp of American Horse the Elder

-

Custer's route over battlefield, as theorized by Curtis.

-

The shallow-draft steamer Far West carried supplies and later wounded men and news of the battle.

-

Crow Scout White Man Runs Him, step-grandfather of Joe Medicine Crow.

-

Pretty Nose who, according to her grandson, was a woman war chief who participated in the battle

-

Henry rifle and a Winchester Model 1866 rifle. These repeater rifles were capable of higher rates of fire than the Springfield trapdoor.

-

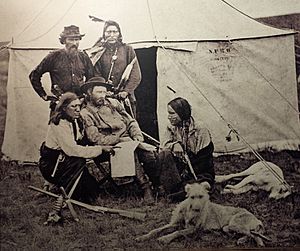

Three of Custer's scouts accompanying Edward Curtis on his investigative tour of the battlefield, circa 1907. Left to right: Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin, White Man Runs Him, Curtis and Alexander B. Upshaw (Curtis's assistant and Crow interpreter)

-

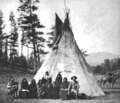

Former U.S. Army Crow Scouts visiting the Little Bighorn battlefield, circa 1913

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Little Bighorn para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Little Bighorn para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |