Belemnitida facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Belemnites |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| The Early Jurassic Passaloteuthis bisulcata showing soft anatomy | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Superorder: | †Belemnoidea |

| Order: | †Belemnitida Zittel, 1895 |

| Suborders | |

|

|

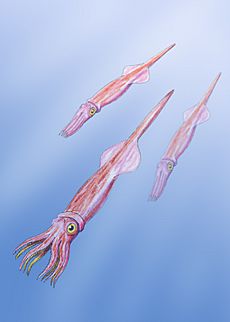

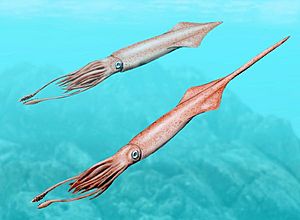

Imagine a creature that looked like a squid but had a hard, spear-shaped internal shell! That's a belemnite (say: BELL-em-nite). These amazing animals lived in the oceans from the Late Triassic to the Late Cretaceous periods. That's about 234 to 66 million years ago!

Unlike today's squid, belemnites had a strong inner skeleton. This skeleton was made of three main parts. The pointy part, called the guard, is the most common fossil we find. Scientists think belemnites had 10 arms with hooks and two fins near their tail. These hooks were small, usually less than 5 mm (0.20 in), but a belemnite could have hundreds of them! They used these hooks to grab their prey.

Belemnites were a very important food source for many ancient sea animals. Both adult belemnites and their tiny babies (larvae) were eaten. They probably helped ocean life recover after a big extinction event between the Triassic and Jurassic periods. Some belemnites might have been fast swimmers in the open ocean. Others lived closer to shore, feeding on the seafloor. The biggest known belemnite, Megateuthis elliptica, had guards that were 60 to 70 cm (24 to 28 in) long!

Belemnites belong to a group called Coleoidea, which includes modern squid and octopuses. Their fossilized guards can tell us a lot about the ancient oceans, like the climate and how the carbon cycle worked. People have found these guards for thousands of years, and they even became part of old stories and folklore.

Contents

What They Looked Like

Their Inner Shell

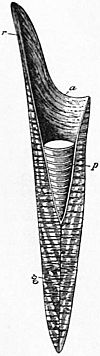

The inner shell of a belemnite had three parts. Starting from the head end, there was a tongue-shaped part called the pro-ostracum. Next was a cone-shaped part with chambers, called the phragmocone. Finally, at the very tip, was the spear-shaped guard. The guard connected to the phragmocone in a special socket.

This inner shell was covered by the belemnite's muscles and other soft tissues. The guard was usually made of a hard material called calcite. The pro-ostracum and phragmocone were made of aragonite. The pro-ostracum likely supported the belemnite's soft body, similar to the "pen" inside a modern squid.

The phragmocone had many small chambers, like the shells of cuttlefish and nautiluses. These chambers probably helped the belemnite float in the water. They might have worked like the modern ram's horn squid. This squid can fill or empty its chambers with water to control its buoyancy (how it floats). At the very tip of the phragmocone, hidden inside the guard, was a tiny cup-like part. This was the remains of the belemnite's shell when it was just an embryo.

The heavy guard at the back likely balanced the weight of the belemnite's head and arms. This helped the animal swim straight through the water. Fins might have been attached to the guard, or the guard might have supported large fins. Including their arms, the guard could make up one-fifth to one-third of a belemnite's total body length.

Soft Body Parts

Belemnites had a "tongue" called a radula, which is a ribbon of teeth. It was similar to those found in modern squid that hunt in the open ocean. Their radula had rows of seven teeth, perfect for catching prey. They also had large statocysts, which are organs that help with balance. This suggests they were fast-moving, like modern squid. Their skin was probably thin and slippery. Their eyes were likely strong and rounded.

Like other cephalopods, belemnites had a mantle cavity. This space held their gills and other organs. Water was sucked into and pushed out of this cavity through a tube called a hyponome. This process helped them move using jet propulsion. However, their large phragmocone meant their mantle cavity was small. This suggests they weren't very efficient at jet propulsion. Instead, they might have used large fins to glide along ocean currents, like some modern squid.

Two fossil specimens of Acanthoteuthis show preserved soft body parts. They had a pair of diamond-shaped fins near the top of their guards. These belemnites seem to have been built for speed. They might have reached speeds similar to modern migrating squid, about 1.1 to 1.8 km/h (0.68 to 1.12 mph).

Arms and Hooks

Belemnites had 10 arms, all about the same length, covered in hooks. These hooks were usually small, less than 5 mm (0.20 in). They got bigger towards the middle of the arm. This might be because the middle of the arm could exert the most power when grabbing prey. A belemnite could have anywhere from 100 to 800 hooks in total.

The hooks were made of chitin, a tough material. They had a base, a shaft, and a sharp, hook-like tip. Only the tip was likely exposed. Different hook shapes probably helped them with different tasks. For example, a very curved hook would stab prey deeply if it tried to escape.

In some species, like Chondroteuthis, large hooks were found near the mouth. These might have been used to surround small prey or ram into larger prey. In modern squid, only adult males have hooks, suggesting they are used for mating. It's possible belemnite hooks could move, like suckers.

Male belemnites, like male squid today, probably had one or two special arms called hectocotyli. These arms were modified and used in fights with other males. Instead of many small hooks, these arms had a pair of very large hooks. These "mega-onychites" helped the male hold onto the female safely during mating, without getting caught by her own hooks.

How They Grew

Belemnites likely laid many eggs, perhaps between 100 and 1,000, in floating egg masses. Their babies might have looked like tiny adults, or they might have gone through a larval stage. In the larval stage, the guard would start to form around the tiny embryonic shell.

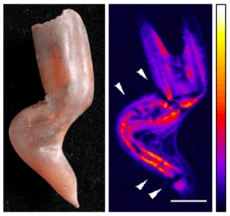

The embryonic shell of Passaloteuthis, a well-studied belemnite, had a tiny first chamber and several other chambers. These chambers might have held gas or liquid to help the embryo float. The early shell and guard were probably made of chitin. This tough material might have helped the embryos survive in deeper, colder waters. It also might have allowed them to grow faster and develop arms before reaching the full phragmocone stage. This could have helped belemnites spread to many different habitats around the world.

Scientists can study the growth of belemnites by looking at the size of the chambers in their phragmocone. Each new chamber tended to be much larger than the last. Unlike some other cephalopods, belemnite embryos probably hatched with only a tiny first chamber. The rest of the phragmocone grew after hatching. This is similar to how ammonites grew, suggesting it was a successful way to reproduce. Belemnite hatchlings were very small, with their first chamber being only about 1.5 to 3 mm (0.059 to 0.118 in) long.

The guards of Megateuthis elliptica are the largest known, reaching 60 to 70 cm (24 to 28 in) in length. The smallest known belemnite, Neohibolites, had guards only about 3 cm (1.2 in) long. By studying growth rings in the guards, scientists believe some belemnites lived for about three to four years. Others, like the mesohibolitid belemnites, lived for about a year. In Megateuthis, the guard fully grew in one or two years, and growth spurts followed the lunar cycle (the phases of the moon).

Injuries and Illnesses

Sometimes, belemnite guards are found with healed fractures. In the past, people thought belemnites used their guards to dig for food on the seafloor. However, scientists now believe belemnites were predators in the open ocean. A deformed, zigzag-shaped guard from a Gonioteuthis belemnite was likely caused by a failed attack from a predator. Other Gonioteuthis guards have double-pointed tips, probably from an injury.

One belemnite guard showed a double-pointed tip with one point higher than the other. This might have been a sign of an infection or a parasite. A Neoclavibelus guard had a large growth on its side, probably from a parasitic infection. A Hibolithes guard showed a large bubble, likely from a parasitic cyst. Another Goniocamax guard had blister-like formations, possibly from a polychaete flatworm infection.

The hard calcite guards were also good places for boring parasites to live. Scientists have found traces of sponges, worms, and barnacles on some guards.

Where They Lived and What They Ate

Their Home

Belemnite fossils are found in areas that were once nearshore or mid-shelf zones. To hunt, they might have quickly or secretly grabbed prey with their hooks, then dived down to eat. It was once thought they lived their whole lives on the shelf, eating crustaceans and other mollusks.

Belemnites with thin guards might have been better swimmers. They could have dived into deeper waters and hunted in the open ocean. Those with heavier guards might have stayed closer to shore, feeding from the seafloor. Generally, they probably preferred water temperatures between 12–25 °C (54–77 °F). Like modern squid, warmer waters might have made them grow and reproduce faster, but also shortened their lives. Most belemnite species probably lived in a narrow range of temperatures. However, Neohibolites lived all over the world during a very warm period called the Cretaceous Thermal Maximum.

Who Ate Them

Belemnites were likely a very common and important food source for many sea creatures during the Mesozoic Era. Their hook remains have been found in the stomachs of ancient crocodiles, plesiosaurs, and ichthyosaurs. They have also been found in the fossilized poop (coprolites) of ichthyosaurs and ancient crustaceans.

Some animals might have only eaten the soft heads of belemnites, leaving the phragmocone and guards behind. However, about 250 Acrocoelites guards were found in the stomach of a 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) Hybodus shark. A fragment was also found in an ancient marine crocodile. This means these predators ate belemnites whole. They might have later spit out the parts they couldn't digest, like modern sperm whales do. To protect themselves, belemnites probably squirted a cloud of ink, just like modern squid.

The tiny belemnite larvae, along with ammonite larvae, were likely at the very bottom of the Mesozoic ocean food webs. They played a bigger role in the ecosystem than the adult belemnites. Giant fish called pachycormids were probably the main filter feeders of that time. They filled a similar role to modern baleen whales.

Large groups of belemnite guards are often found together. These places are sometimes called "belemnite battlefields." One idea is that belemnites, like modern squid, died shortly after laying their eggs. They might have migrated from the open ocean to shallower areas to spawn. Another idea is that large groups of belemnites were killed by things like volcanoes, changes in water saltiness or temperature, or harmful algae blooms. Some "battlefields" might just be places where ocean currents gathered the guards. Others could be piles of indigestible parts spit out by a predator.

Their End

Squid and octopuses became more common and started to outcompete belemnites from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous periods. Belemnites slowly declined through the Late Cretaceous. Their range became smaller, mostly limited to the polar regions. The last belemnites, from the family Belemnitellidae, lived in what is now northern Europe. They finally died out during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, about 66 million years ago. This was the same event that killed the dinosaurs. Scientists think the tiny first chambers of belemnite embryos couldn't survive the ocean becoming more acidic. After belemnites disappeared, tiny floating snails called sea butterflies took their place at the bottom of the food chain.

Belemnites in Culture

People have known about belemnite guards for a very long time. Many folk tales have grown around them. Before people knew they were fossils, they thought the guards were special gemstones. After a thunderstorm, guards would sometimes be found in the soil. People believed these were lightning bolts thrown from the sky. This belief still exists in some parts of rural Britain today.

In old German stories, belemnites had at least 27 different names. Some names were Fingerstein ("finger stone"), Teufelsfinger ("Devil's finger"), and Gespensterkerze ("ghostly candle"). In Southern England, the pointy guards were used to try and cure rheumatism. They were also ground up to cure sore eyes, which actually made the problem worse! In Western Scotland, people put them in water to cure a horse illness called distemper.

The Belemnitella belemnite was named the state fossil of Delaware in the United States on July 2, 1996.

Images for kids

-

Cephalopod embryonic shells. A) Ammonoidea (B) Sepiida (C) Belemnoidea (D) Spirulida (E) Orthocerida (F) Nautilida (G) Oncocerida (H) Pseudorthocerida (I) Oegopsina (J) Bactritida. IC indicates the initial chamber.

-

Opalized Peratobelus guard from the Early Cretaceous

See also

In Spanish: Belemnitida para niños

In Spanish: Belemnitida para niños

- Ammonoidea

- Belemnoidea

- Orthoceratoidea

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |