Bert Williams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bert Williams

|

|

|---|---|

Williams, c. 1921

|

|

| Born |

Egbert Austin Williams

November 12, 1874 |

| Died | March 4, 1922 (aged 47) Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

|

| Other names | Egbert Austin Williams |

| Occupation | Entertainer, actor, comedian |

| Years active | 1892–1922 |

| Spouse(s) | Lottie Williams (née Thompson) |

Bert Williams (born November 12, 1874 – died March 4, 1922) was a famous Bahamian-born American entertainer. He was one of the most important performers during the Vaudeville era and a very popular comedian for all kinds of audiences.

He is known for being the first Black person to have a main role in a movie, Darktown Jubilee, in 1914. Before 1920, he was also the best-selling Black music artist. In 1918, a newspaper called him "one of the great comedians of the world."

Bert Williams was a key figure in the history of African-American entertainment. At a time when racial unfairness was common, he became the first Black person to have a lead role on a Broadway stage. He helped break down racial barriers during his 30-year career. Another vaudeville performer, W. C. Fields, who worked with Williams, said he was "the funniest man I ever saw—and the saddest man I ever knew."

Contents

Early Life and Partnership

Bert Williams was born in Nassau, The Bahamas, on November 12, 1874. When he was 11, he moved with his parents to Florida in the US. The family soon moved to Riverside, California, where he finished high school in 1892.

In 1893, as a teenager, he joined different minstrel shows on the West Coast. In San Francisco, he met George Walker, who would become his professional partner.

Williams & Walker: A Famous Duo

Williams and Walker performed song-and-dance numbers, funny conversations, and skits. At first, Williams played a clever character, and Walker played a silly character. But they found that audiences liked it better when they switched roles. Walker became known for playing a fancy, strutting man, while Williams played a slow-moving, clumsy character.

Even though Williams was a bit heavy, he was amazing at using his body and facial expressions to make people laugh. A reviewer from The New York Times wrote that he could hold a funny face for a long time and make people laugh with just a small movement.

In 1896, Williams and Walker became very popular. They performed at a top vaudeville theater for 36 weeks. Their energetic version of the cakewalk dance helped make it famous. They performed in blackface, which was a common practice at the time. They called themselves "Two Real Coons" to show they were different from white performers who also used blackface.

Williams and Walker were careful about how they presented themselves. In their publicity photos, they always looked very neat and well-dressed. This showed a contrast between their real-life appearance and the funny characters they played on stage.

In 1899, Williams married Charlotte ("Lottie") Thompson, a singer he had worked with. Lottie was a widow older than Bert, but they were a very happy couple until his death. They never had their own children but adopted and raised three of Lottie's nieces. They also often took in orphans and foster children.

Facing Challenges

Williams & Walker performed in many shows, like A Senegambian Carnival and The Policy Players. They were becoming very successful, but they still faced racial challenges. In August 1900, in New York City, there was a riot. Williams and Walker left the theater after a show and went separate ways. Williams was safe, but Walker was pulled from a streetcar by a white crowd and beaten.

Broadway Success

The next month, Williams & Walker had a huge success with Sons of Ham. This was a funny play that did not use any of the extreme, harmful stereotypes that were common then. One of the songs, "When It's All Going Out and Nothing Coming In," was about money troubles and became one of Williams's most famous songs.

In September 1902, Williams & Walker launched their next big show, In Dahomey. This was a full-length musical created and performed entirely by Black artists. It was an even bigger hit. In 1903, the show moved to New York City. This was a landmark event because it was the first musical like this to be shown at a major Broadway theater. However, seating in the theater was still separated by race.

One of the musical's songs, "I'm a Jonah Man," helped define the unlucky character Williams often played. This character was a slow-talking, thoughtful person who always seemed to have bad luck. Williams once explained, "Even if it rained soup, [my character] would be found with a fork in his hand and no spoon in sight."

In Dahomey also traveled to London and was very popular there. They even performed for the King and Queen at Buckingham Palace in June 1903.

Abyssinia and "Nobody"

Williams and Walker's international success made them the most famous Black performers in the world. They wanted to create a new, even bigger show. In February 1906, Abyssinia, which Williams helped write, opened. This show, which even included live camels, was another huge success.

The show also included hints of a love story, which had never been allowed in a Black stage production before. Walker played a tourist, and his wife, Aida, played an Abyssinian princess.

While the show was praised, some white critics were uncomfortable with the Black cast's ambitions. One critic said that audiences "do not care to see their own ways copied when they can have the real thing better done by white people." George Walker was not bothered by this, saying, "It's all rot, this slapstick bandanna handkerchief bladder in the face act, with which negro acting is associated. It ought to die out and we are trying to kill it."

Williams recorded many of Abyssinia's songs. One of them, "Nobody", became his signature song. It was a sad and funny song, full of his dry humor, and it fit Williams' quiet, almost spoken singing style perfectly.

Williams became so known for "Nobody" that he had to sing it almost every time he performed for the rest of his life. He felt its success was both a blessing and a curse. "Nobody" sold between 100,000 and 150,000 copies, which was a huge number for that time.

Williams' slow, drawn-out way of singing made many of his recordings popular. His style was unique. He said about his character: "When he talks to you it is as if he has a secret to confide that concerns just you two."

Solo Career

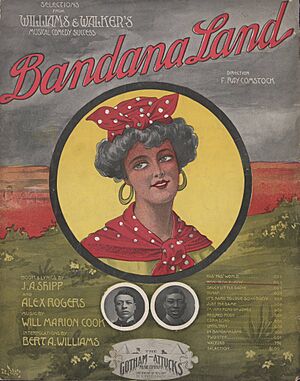

In 1908, while starring in the successful Broadway show Bandanna Land, Williams and Walker were asked to perform at a charity event. A white performer named Walter C. Kelly protested and tried to get other acts to refuse to perform with Black performers. Only two acts joined his boycott.

Bandanna Land continued the duo's hits and featured a famous sketch by Williams: his silent poker game. Without saying a word, Williams acted out a poker hand, using only his face and body to show his character's feelings. This later became a regular part of his solo act and was filmed in 1916.

Going Solo

By this time, George Walker was very sick. In January 1909, he had a stroke on stage and had to leave Bandanna Land. The famous duo never performed together again, and Walker died less than two years later. Walker had been the business manager and public speaker for the duo, so Williams felt lost without him.

After 16 years as part of a duo, Williams had to start over as a solo act. In May 1909, he returned to the vaudeville circuit. His new act included songs, funny monologues, and a dance. He was given top billing and a high salary. However, a group of vaudeville performers called the White Rats of America tried to get theaters to lower Williams' billing because he was Black. Williams did not protest, even though Walker would have.

Williams often had to travel, eat, and stay in different places from other performers because of his race. This made him feel even more alone after losing Walker.

Williams then starred in Mr. Lode of Koal, a funny play about a kidnapped king. Critics liked Williams' performance, but the show itself did not do well.

Joining the Ziegfeld Follies

After Mr. Lode of Koal ended, Williams accepted a special offer to join Flo Ziegfeld's Follies. In 1910, having a Black performer in an all-white show was a big shock. At first, some cast members wanted Williams fired, but Ziegfeld insisted, saying, "I can replace every one of you, except [Williams]."

By the time the show opened in June, Williams was a huge hit. He performed his usual acts and also appeared in a boxing sketch. Reviews for Williams were very positive.

After his success, Williams signed a special contract with Columbia Records. His new status was clear from the generous contract and how Columbia promoted him. They stopped using old-fashioned sales talk and started praising Williams' "unique art." He became a star who went beyond racial limits, as much as possible in 1910. All his songs sold well, and "Play That Barbershop Chord" became a big hit.

Williams returned for the 1911 Ziegfeld Follies. He teamed up with comedian Leon Errol in some sketches, and they were amazing together. Their best sketch showed Errol as a tourist and Williams as a porter leading him across high beams in the unfinished Grand Central Station. Williams and Errol wrote this sketch themselves, making it a 20-minute highlight of the show.

The pairing of Williams, a Black performer, with the white Leon Errol was groundbreaking on Broadway. Williams often delivered most of the punchlines and usually got the better of Errol. At the end of their Grand Central Station routine, Errol offered Williams a tiny tip. Williams then deliberately loosened Errol's rope, sending him falling.

Williams continued to be the featured star of the Follies, signing a three-year contract for a very high salary. By 1912, he was even allowed to be on stage at the same time as white women, which was a big step.

He also started appearing in films, though most of them are now lost. One film, A Natural Born Gambler, shows his silent poker sketch. Another film, Lime Kiln Field Day, which featured an all-Black cast, was found and shown in 2014.

Williams did not appear in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1913. Instead, he joined an all-Black show by The Frogs, a Black theater group. For many of his Black fans, this was the first time they had seen him on stage since before he joined the Follies. After this tour, Williams went back to vaudeville, where he was the highest-paid Black performer ever.

He returned to the Follies in 1914, but as the show became bigger, Williams and other performers were given less stage time. This continued in 1915 and 1916.

The 1917 Follies had many talented performers, including Williams, W. C. Fields, Fanny Brice, Will Rogers, and Eddie Cantor. Williams and Cantor performed scenes together and became close friends. In 1918, Williams took a break from the Follies because he felt the show wasn't giving him good parts. He then performed in another Ziegfeld show, Midnight Frolic, where he had more stage time for his routines. He returned to the Follies of 1919, but again, the material was not very good.

Between 1918 and 1921, he recorded several songs as "Elder Eatmore," a tricky preacher. He also recorded songs about Prohibition, like "Everybody Wants a Key to My Cellar" and "The Moon Shines on the Moonshine." By this time, Williams' records were very popular and among the best-selling songs of the era. He was one of the highest-paid recording artists in the world.

Later Life and Passing

Even with all his success, Williams still faced challenges. In 1919, when the Actors Equity union went on strike, the entire Follies cast walked out, but Williams was not told about it. He showed up to an empty theater. He told W. C. Fields, "I don't belong to either side. Nobody wants me."

Williams continued to face institutional racism, but his success helped him deal with it. Once, when he tried to buy a drink at a fancy hotel bar, the bartender tried to charge him $50 to make him leave. Williams pulled out a thick roll of hundred-dollar bills and ordered drinks for everyone in the room. He told a reporter, "They say it is a matter of race prejudice. But if it were prejudice a baby would have it, and you will never find it in a baby... I have notice that this 'race prejudice' is not to be found in people who are sure enough of their position to defy it."

Williams' stage career slowed down after his last Follies appearance in 1919. He developed pneumonia but kept performing because he knew the show depended on him. However, he also suffered from the racial politics of the time and felt he was not fully accepted. He often felt sad in his later years.

On February 27, 1922, Williams collapsed during a performance in Detroit, Michigan. The audience first thought it was part of his act. As he was helped to his dressing room, Williams joked, "That's a nice way to die. They was laughing when I made my last exit." He returned to New York, but his health got worse. He passed away at his home in Manhattan, New York City on March 4, 1922, at the age of 47.

Many people did not know he was sick, so his death was a shock. More than 5,000 fans came to see his casket, and thousands more could not get in. A private service was held at the Masonic Lodge in Manhattan, where Williams broke another barrier. He was the first Black American to be honored by the all-white Grand Lodge. When the Masons opened their doors for a public service, nearly 2,000 mourners of all races were admitted. Williams was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Legacy

In 1910, Booker T. Washington wrote about Williams: "He has done more for our race than I have. He has smiled his way into people's hearts; I have been obliged to fight my way."

- In 1940, Duke Ellington created a musical tribute called "A Portrait of Bert Williams."

- In 1978, Ben Vereen performed a tribute to Williams on a TV special, including his dance steps and classic songs.

- The 1975 musical Chicago has a character, Amos Hart, whose personality is based on Bert Williams. Hart's song, "Mister Cellophane," is like Williams' "Nobody."

- In 1996, Bert Williams was inducted into the International Clown Hall of Fame.

- The Archeophone label has released all of Williams' existing recordings on three CDs.

- The novel Dancing in the Dark (2005) tells the story of Bert Williams' life.

- The play Nobody (2008) focuses on Williams' and George Walker's time in vaudeville.

In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS Bert Williams was named in his honor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bert Williams (cómico) para niños

In Spanish: Bert Williams (cómico) para niños

- The Frogs (club)

- African American musical theater

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |