Beth Hamedrash Hagodol facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Beth Hamedrash Hagodol(Norfolk Street Baptist Church) |

|

|---|---|

|

Hebrew: בֵּית הַמִּדְרָש הַגָּדוֹל

|

|

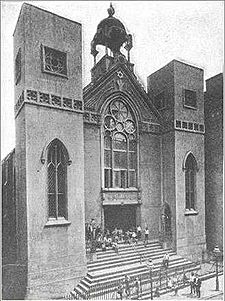

Beth Hamedrash Hagodol façade in 2008,

before the 2017 fire and subsequent demolition |

|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Orthodox Judaism (former) |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Location | |

| Location | 60–64 Norfolk Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan, New York City, New York |

| Country | United States |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Architectural type | Church |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| Founder | Rabbi Abraham Joseph Ash |

| Date established | 1852 (as Beth Hamedrash congregation) |

| Groundbreaking | 1848 |

| Completed | 1850 |

| Demolished | May 14, 2017 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | West |

| Capacity | 1,200 |

| Materials |

|

Beth Hamedrash Hagodol (which means "Great Study House" in Hebrew) was an Orthodox Jewish congregation. For over 120 years, it was located in a historic building at 60–64 Norfolk Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York City. It was the first Jewish congregation in New York City started by people from Eastern Europe. It was also the oldest Russian Jewish Orthodox congregation in the United States.

The congregation began in 1852 as Beth Hamedrash. Rabbi Abraham Joseph Ash founded it. The group split in 1859. Rabbi Ash and most members renamed their congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagodol. The building, built in 1850, was first a Baptist church. It was bought by the congregation in 1885. It was one of the largest synagogues on the Lower East Side.

In the late 1900s, the congregation became very small. They could not keep up the building. It was damaged by storms. Even with money and grants, the building was in danger. The synagogue closed in 2007. The building was largely destroyed by a fire on May 14, 2017. It was later taken down.

Contents

Early Beginnings

Beth Hamedrash Hagodol was started by Eastern European Jews in 1852. It was first called Beth Hamedrash, meaning "House of Study". This term was often used for a synagogue. The first rabbi, Abraham Joseph Ash, was born in Poland. He moved to New York City around 1851 or 1852. He was the first Orthodox rabbi from Eastern Europe to serve in the United States. Rabbi Ash did not like the changes made by German Jewish congregations.

He soon gathered a minyan, which is a group of ten Jewish adults needed for prayer. By 1852, they began holding services. Most members were Polish Jews, but some were from Lithuania, Germany, and England. For the first six years, Rabbi Ash was not paid as a rabbi. He worked as a peddler to earn money.

The congregation moved often in its early years. In 1856, they bought a Welsh chapel on Allen Street. This was helped by generous people like Sampson Simson. The synagogue had a good Hebrew library. It was a place for prayer and study. It also had a Jewish court. According to Judah David Eisenstein, a long-time member, it quickly became a main center for Orthodox Jewish guidance in the country.

The shamash, like a caretaker, collected synagogue dues. He also worked as a glazier (someone who fits glass) and sold snacks. Mourners could buy a piece of cake and a small glass of brandy for ten cents. This was a common practice.

Beth Hamedrash was a model for early immigrant Eastern European Jews. They started coming to the United States in large numbers in the 1870s. They found German Jewish synagogues unfamiliar. Unlike German Jews, the founders of Beth Hamedrash saw religion and the synagogue as central to their lives. They tried to create a synagogue like the ones they knew in Europe.

Congregation Splits

In 1859, a disagreement happened between Rabbi Ash and the synagogue's president, Joshua Rothstein. The argument was about who was in charge. This led to problems in the synagogue. After a court case, most members left with Rabbi Ash. They formed Beth Hamedrash Hagodol. They added "Hagodol" (meaning "Great") to the name.

Rothstein's followers stayed at the Allen Street location. They kept the name "Beth Hamedrash" for a while. Their group became smaller and had less money. They later joined with another congregation. This new group became known as Kahal Adath Jeshurun. They built the Eldridge Street Synagogue.

Beth Hamedrash Hagodol offered a "socially religious" atmosphere. Members combined faith with enjoyment. They called their synagogue a shtibl, or prayer-club room. They wanted everyone to join in and chant prayers. They did not like formal services. However, members carefully followed Jewish dietary laws. They even watched their own matzos being baked for Passover.

The congregation first moved to a building on Grand and Forsyth Streets. In 1865, they moved to a former courthouse on Clinton Street. In 1872, the congregation built a synagogue at Ludlow and Hester Streets. Younger members gained more control there. They made some small changes. For example, they hired a professional cantor in 1877. This was to make services more formal and attract new members. Even with these changes, the congregation remained very traditional. Men and women sat separately. They followed the full service in the traditional prayer book. They also trained men for rabbinic ordination. Study groups for Talmud and Mishna were held mornings and evenings.

Rabbi Ash served as rabbi only sometimes during this period. He had other business ventures. Some members also had issues with his scholarship. Ash resigned as rabbi in 1877. In 1879, Beth Hamedrash Hagodol directors suggested hiring a Chief Rabbi for New York. They re-hired Ash as congregational rabbi for $25 a month. The next year, they hired a new cantor for $1,000 a year. This was more than three times Ash's salary.

The Norfolk Street Building

The congregation's building at 60-64 Norfolk Street was originally the Norfolk Street Baptist Church. It was built in 1850. The church was designed in the Gothic Revival style. The architect is unknown. The front of the building was covered in stucco to look like smooth stone. The other sides were brick.

The neighborhood around the church changed quickly. Many Irish and German immigrants moved in. The Baptist church members moved uptown. They sold their building in 1860. It was bought by Alanson T. Biggs, a local merchant. Biggs changed the church for Methodists. In 1862, he gave ownership to the Alanson Methodist Episcopal Church.

The Methodist congregation did well for a time. But then it declined and had money problems. In 1878, the church was given to the New York City Church Extension and Missionary Society. This group helped build or support Methodist churches in poorer areas. By 1884, they realized the Norfolk Street church was too big and costly. They put it up for sale.

In 1885, Beth Hamedrash Hagodol bought the building for $45,000. They spent $10,000 on changes and repairs. They did not change the outside much at first. Inside, they added an Ark for Torah scrolls. They also added an "eternal light" and a bimah (a raised platform for reading the Torah). A women's gallery was added around three sides. The sanctuary ceilings were painted bright blue with stars.

The congregation wanted the large building to show respectability for Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Other Lower East Side congregations also bought or built new buildings around this time. They also hired more expensive cantors. By 1888, Beth Hamedrash Hagodol's members included bankers, lawyers, and merchants.

The building had some changes over time. In the early 1890s, the rose window on the front was removed. It was replaced with a large arched window. This work was done by architects Schneider & Herter. They also fixed "serious structural problems" in 1893. This included adding brick supports to the sides of the church. Later, the wooden stairs inside were replaced with iron ones.

Two Stars of David were added to the front. One is still visible today. A panel with Hebrew writing was added over the main doors. Other decorations on the upper parts of the facade were removed after they wore out.

Rabbi Jacob Joseph's Time

Rabbi Ash died in 1887. The Association of American Orthodox Hebrew Congregations looked for a new rabbi. He would serve Beth Hamedrash Hagodol and be the Chief Rabbi of New York City. They chose Jacob Joseph. He was the first, and only, Chief Rabbi of New York City.

Rabbi Joseph was born in Lithuania. He was known for his sharp mind. He arrived in New York on July 7, 1888. Later that month, he gave his first Sabbath sermon at Beth Hamedrash Hagodol. Many people came to hear him speak. Over 1,500 men filled the sanctuary. Thousands more were outside. Police had to control the crowd.

Rabbi Joseph tried to organize the kosher meat business in New York. He issued new rules to follow Jewish law. Funds for this were to come from a small increase in meat prices. However, vendors and customers did not want to pay this. They compared it to a disliked tax in Russia. Rabbi Joseph never fully succeeded in organizing the kosher meat business.

He also could not stop people from breaking the Sabbath. His Yiddish sermons did not connect with the younger generation. He faced many challenges. He had no experience running an organization. Other rabbis did not accept his authority. Non-Orthodox groups also criticized him. These problems got worse after he had a stroke in 1895. He became bedridden in 1900.

In the late 1800s, many New York City synagogues served Jews from a single town in Europe. Beth Hamedrash Hagodol welcomed all Jews, no matter where they came from. The synagogue's Passover Relief Committee helped poor Jews. They gave money and food so everyone could celebrate Passover. By 1900, the synagogue gave about $800 a year to the poor for Passover. This was in addition to weekly contributions. By 1901, the synagogue had 150 members.

During Rabbi Joseph's time, Beth Hamedrash Hagodol helped start the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America. This group is now called the "Orthodox Union". In 1898, officials from many Orthodox synagogues met to create the organization. By the 1980s, the Orthodox Union had over 1,000 member congregations.

Rabbi Joseph served as the synagogue's rabbi from 1888 until his death in 1902. His family became poor because he did not receive his full salary. After he died, Beth Hamedrash Hagodol buried him in its cemetery. His funeral was attended by up to 100,000 mourners.

After Rabbi Joseph

Rabbi Shalom Elchanan Jaffe became the next rabbi. He was a founder of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis. He was also a strong supporter of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary. Rabbi Jaffe was an important rabbi on the Lower East Side. This was partly because he oversaw kosher supervision for butcher shops and slaughterhouses in New York.

By 1908, Beth Hamedrash Hagodol had 175 member families. The synagogue's yearly income was $10,000. In 1909, the synagogue hosted a large meeting. It protested what was called "malicious misrepresentation of Judaism" by some rabbis. In 1913, another important meeting was held there. It raised money for the first Young Israel synagogue. Membership had dropped to 110 families by 1919.

Dr. Benjamin Fleischer became the rabbi in 1924. He was a well-known speaker. In May 1939, he and two other rabbis formed the first permanent beth din (court of Jewish law) in the U.S.

In the early to mid-1900s, the congregation still had money problems. The building needed repairs. In the 1930s or 1940s, the walls inside the sanctuary were painted with colorful pictures. These showed Jerusalem and Holy Land landscapes. At the end of 1946, the president said that if $35,000 was not raised, the building would have to be torn down.

Ephraim Oshry, a famous Torah scholar, became the synagogue's rabbi in 1952. He stayed for over 50 years. During the Holocaust, he was forced to be a custodian of Jewish books. He used these books to write answers to questions about how Jews could follow Jewish law under harsh conditions. He also held secret worship services. After the war, he founded religious schools in Italy and Montreal. Then he moved to New York. His Sunday afternoon lectures were very popular. The 1,200-seat sanctuary was always full. He also founded another religious school for gifted high school boys.

The synagogue building was again threatened with demolition in 1967. But Rabbi Oshry worked to have it named a New York City landmark. This saved it. At that time, the congregation said it had 1,400 members.

In 1974, the building was considered for the National Register of Historic Places. Its condition was described as "excellent." The building was repainted and repaired in 1977. But in later years, it became damaged.

Recent History and Fire

In 1997, a storm broke the main two-story window at the front of the building. The window frame was rotten. The window was not fixed for a month. The congregation, with only about 100 members, asked for help. They had been holding services in a smaller room. They used the main sanctuary only for the High Holidays. They received some money for a temporary window. In 1999, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The congregation raised $40,000 in 2000 for emergency repairs. They also received a $230,000 grant for restoration work, including roof repair. But they could not raise the matching money needed for the grant. On December 6, 2001, a fire badly damaged the roof, ceiling, and paintings.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation named the building an endangered historic site in 2003. It was the only synagogue on that list. It still had many important features. These included the ornate ark, the central bimah, and painted walls. That same year, Rabbi Oshry died. His son-in-law, Rabbi Mendl Greenbaum, became the new rabbi.

By 2006, $1 million had been raised for repairs. An estimated $3.5 million was needed. In 2007, Rabbi Greenbaum decided to close the synagogue. Its membership had shrunk to about 15 people. The building was mostly closed because it was unsafe. The synagogue, once home to the oldest Orthodox congregation in New York, sat "padlocked and empty." It had holes in the roof. In 2011, the Buildings Department ordered it to be vacated.

The Lower East Side Conservancy tried to raise $4.5 million for repairs. They wanted to turn the building into an educational center. They received grants from the United States Department of Education and the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. Rabbi Greenbaum's group had about 20 regular members. They were sharing facilities with another congregation.

By the end of 2012, over a million dollars in grants for repairs had not been used. They were taken back. In December 2012, the synagogue leadership asked for permission to tear down the building. They wanted to build new homes there. This request was withdrawn in March 2013. But some groups said the building was being allowed to fall apart.

The 2017 Fire

On May 14, 2017, a large fire started in the unused synagogue. An eyewitness reported a "big explosion." About 150 firefighters controlled the fire around midnight. During the fire, Rabbi Yehuda Oshry, Rabbi Ephraim Oshry's son, was allowed to save the Torah scrolls. The fire "largely destroyed" the building. The next day, the fire seemed "suspicious." Video showed three young people running from the area just before the fire. The fire caused the ceiling and walls to fall. This created a 15-foot pile of rubble. A 14-year-old boy was arrested three days later. He was charged with setting the fire.

After the fire, the synagogue began steps to possibly tear down the building. The city's Department of Buildings said the remains were unstable. They did not approve an emergency demolition. So, a board member asked for a general demolition permit. The city's Landmark Preservation Commission (LPC) gave a permit on July 11. It allowed removal of unsafe parts. Other parts had to be checked for preservation. Parts of the damaged synagogue were taken down by early 2018.

After the fire, a plan was made to include parts of the synagogue building in a new 30-story residential development. However, in June 2019, engineers said the remains of the south tower had to be destroyed. This was because it was not stable. A worker died in October 2019 after part of the burned building collapsed. An investigation found that an engineer and a demolition company had recommended tearing down the whole building. But the city's Department of Buildings had refused to overrule the LPC. A housing lottery for the new residential building at 60 Norfolk Street, which replaced the synagogue, started in 2022.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sinagoga Beth Hamedrash Hagodol para niños

In Spanish: Sinagoga Beth Hamedrash Hagodol para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |