Blockade of Saint-Domingue facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Blockade of Saint-Domingue |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Haitian Revolution and Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

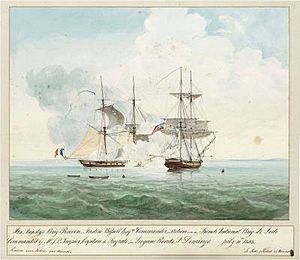

A painting of the campaign by Louis-Philippe Crépin |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7 ships of the line 5 frigates 2 brigs |

7,000 2 ships of the line 6 frigates 35 other ships |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 6,000 captured 1 ship of the line captured 4 frigates captured 31 other ships captured |

||||||

| 6 American merchantmen captured 2 Danish merchantmen captured |

|||||||

The Blockade of Saint-Domingue was a naval campaign. It happened during the first part of the Napoleonic Wars. British Royal Navy ships blocked the French-controlled ports of Cap-Français and Môle-Saint-Nicolas. These ports were on the northern coast of Saint-Domingue. This colony would soon become Haiti.

In the summer of 1803, war started between the United Kingdom and France. By then, Haitian troops, led by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, had taken over most of Saint-Domingue. French forces were stuck in Cap-Français and Môle-Saint-Nicolas. These ports were supplied by French navy ships.

When the war began on May 18, 1803, the British Navy sent ships. Sir John Duckworth led a group from Jamaica. Their goal was to stop French ships and capture them. On June 28, they found a French convoy near Môle-Saint-Nicolas. They captured one ship, but another got away.

Two days later, they caught another French ship. On July 24, a British group led by Commodore John Loring stopped the main French fleet. This fleet was trying to escape the blockade and reach France. The British chased them. One French ship and a frigate escaped. Another ship was trapped near the coast and captured. The rest of the French fleet had to fight two more battles. They finally reached the Spanish port of Corunna.

On November 3, the British ship HMS Blanche captured a supply ship. By the end of November, the French soldiers were starving. Their commander, Rochambeau, agreed to leave the port by December 1. But Loring, the British commander, would not let them sail.

Rochambeau waited until the last moment. He was then forced to surrender to the British. One of his ships almost crashed while leaving the harbor. A brave British lieutenant saved it. He rescued 900 people and got the ship floating again. At Môle-Saint-Nicolas, General Louis Marie Antoine de Noailles refused to surrender. He sailed to Havana, Cuba on December 3. But a British ship stopped him, and he was badly hurt. The few remaining French towns in Saint-Domingue surrendered soon after. On January 1, 1804, the new nation of Haiti became independent.

Contents

Why the Blockade Happened

The French colony of Saint-Domingue was very rich. It was on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea. During the French Revolutionary Wars, there was a lot of fighting there. The British and Spanish tried to invade but failed. There was also a civil war. Black people, who were newly freed from slavery, fought against French forces. They were led by Toussaint Louverture.

By 1801, Louverture controlled almost the whole island. He said he was loyal to France and became the island's governor. But after the Peace of Amiens in 1802, French leader Napoleon Bonaparte sent a large army. General Charles Leclerc led this army to Saint-Domingue.

Leclerc's army had some early success. Louverture was captured and later died in a French prison. But after Louverture's arrest, the Haitian general Jean Jacques Dessalines started fighting again. The French had threatened to bring back slavery. Leclerc and many of his soldiers died from yellow fever in late 1802. Command then went to Rochambeau. His forces were pushed back into a few strong towns. They relied on ships for supplies.

In May 1803, things got even worse for the French. Britain and France went to war again. This was after only 15 months of peace. The French had ordered some ships to leave Saint-Domingue. But these ships were captured by the British. The remaining French navy ships gathered at Cap-Français.

The British Blockade Begins

The British Navy was ready for the new war. They had many ships at their base in Jamaica. Rear-Admiral John Duckworth was in charge. On June 18, 1803, two groups of ships were sent out. Their job was to block the main French ports: Cap-Français and Môle-Saint-Nicolas.

One group of ships blocked Môle-Saint-Nicolas. It included three large ships: HMS Cumberland, HMS Goliath, and HMS Hercule. The second group blocked Cap-Français. Commodore John Loring led this group in HMS Bellerophon. It also had HMS Elephant, HMS Theseus, and HMS Vanguard. Two smaller ships, HMS Aeolus and HMS Tartar, were also with Loring.

Battles Near Môle-Saint-Nicolas

On June 28, the British ships near Môle-Saint-Nicolas saw two French ships. These were the frigate Poursuivante and the smaller ship Mignonne. They were sailing from Les Cayes to Môle-Saint-Nicolas. The British ships split up to chase them.

Captain Charles Brisbane chased Mignonne. The French ship was stuck in calm waters. Its captain surrendered without a fight. Mignonne was later added to the British Navy.

Lieutenant John B. Hills chased Poursuivante. His ship, Hercule, was slower in the light winds. The French ship got closer to the shore. When Hercule finally caught up, a short battle began. Both ships were damaged. Hercule had minor damage. Poursuivante was hit harder, with six men killed and 15 wounded. The French captain managed to get his ship into shallow water. Hercule had to pull back to avoid getting stuck. Poursuivante escaped to France. Hercule went to Jamaica for repairs.

Two days later, the British ships Vanguard and Cumberland saw another French ship. It was the frigate Créole. It was carrying 530 French soldiers. But many of its crew were sick with yellow fever. The British ships quickly caught up to it. After a few shots, the French ship surrendered. Créole was taken to Jamaica. It was later added to the British Navy but sank on its way to Britain. A French ship carrying 100 bloodhounds for the French army was also captured.

French Ships Try to Escape

For a month, there was little action from the French ships. Yellow fever was spreading in the harbors. The British blockade kept them trapped. On July 11, a small French ship called Lodi was captured by the British ship HMS Racoon.

In late July, the French squadron at Cap-Français was ordered to return to France. Contre-Admiral Latouche Tréville was in charge. He managed to get enough healthy sailors for three ships: Duquesne, Duguay-Trouin, and the frigate Guerrière. On July 24, a rainstorm pushed the British ships away. The French ships slipped out of the harbor. They were all weak, with few crew members and many sick passengers.

The British ships saw them right away and started chasing. The French ships split up. Duguay-Trouin sailed east, and Duquesne went west. The British ships chased both. On July 25, Duquesne was spotted by Haitian soldiers on shore. The Haitians started firing. The British ships closed in. The French ship was too weak to fight. It had only 275 crew, and only 215 were fit. The French captain surrendered. Duquesne was taken by the British.

The chase for Duguay-Trouin continued. The British ship Elephant caught up. Duguay-Trouin fired its back guns, hitting Elephant a few times. Then, another British ship and the French frigate Guerrière appeared. The British commander thought the French ships were too strong together and let them escape. This was a mistake, as the French ships were very weak. They sailed into the open ocean, heading for France.

But their journey was not over. On August 29, near France, they were seen by the British frigate HMS Boadicea. The British ship chased them. The French ships turned towards a Spanish port. The British ship fired at Duguay-Trouin. The French ship fired back strongly. The British ship pulled away. The French ships then sailed to the Spanish port of Corunna.

At Corunna, another British fleet was waiting. On September 2, the French ships appeared. A British ship, HMS Culloden, tried to stop them. The French ships were faster. Duguay-Trouin entered Corunna safely. Guerrière was badly damaged by Culloden's fire but also made it into the port.

Cap-Français Surrenders

With the main French warships gone, only frigates were left at Cap-Français. In September, the southern port of Les Cayes surrendered to the British ship HMS Pelican. In the north, Captain Bligh in Theseus attacked Fort Labouque on September 8. This fort was important for supplying Cap-Français. The fort surrendered quickly. A French ship nearby also surrendered. Bligh helped free French soldiers captured by the Haitians. He took all prisoners to Cap-Français.

In October, Latouche-Tréville returned to France due to bad health. Captain Jean-Baptiste Barré took command. The French ports were under siege by Haitian forces. On November 3, the British ship HMS Blanche captured a ship carrying cattle for the French soldiers. On November 16, Vanguard captured an American ship trying to enter Cap-Français.

On November 17, Rochambeau asked Loring for permission to leave Cap-Français safely. Loring refused. So, on November 20, Rochambeau made a deal with Dessalines. The French soldiers and people had to leave the port within ten days. Loring knew about this deal. Even though Rochambeau was ready to leave on November 25, the British ships blocked all escape routes.

On November 30, Haitian soldiers took over the forts. They were ready to fire hot cannonballs at the French ships if they didn't leave. Loring sent Captain Bligh to offer surrender terms to Rochambeau.

Bligh met with Captain Barré. They signed a treaty for Rochambeau's full surrender to the British. The French ships would sail out, fire a salute, and then surrender to Loring. Bligh then convinced Dessalines to let the French leave safely. Dessalines agreed but would not provide pilots for the harbor.

Rochambeau sailed out first in Surveillante. He fired his salute and lowered his flag to Loring. Other French ships followed, full of refugees. These ships were taken as prizes by the British. French hospital ships were also surrendered. They were full of sick soldiers and sent back to France. Five American and two Danish ships, also full of refugees, were seized. Duckworth arrived and helped with the evacuation.

But then, the frigate Clorinde tried to leave. It had 900 people on board. It accidentally hit rocks right under a fort now held by Haitian soldiers. The ship was stuck and badly damaged. Many British boats turned away, thinking it was hopeless. But Acting-Lieutenant Nesbit Willoughby in a small boat from Hercule went to help.

Willoughby knew his boat would sink if too many people jumped in. So he got on board Clorinde alone. He convinced the French general to surrender the ship to the British. He raised the British flag. This stopped the Haitians from firing on the ship. Willoughby then met with Dessalines, who promised help. Willoughby returned with Haitian boats and some British boats. The wind had calmed down, so they were able to pull Clorinde off the rocks. The ship was still in one piece. By evening, Clorinde joined the British fleet.

What Happened Next

With Cap-Français surrendered, the Haitian Revolution was almost over. Only Môle-Saint-Nicolas was still held by the French. On December 2, Loring's ships arrived there. They offered General Louis Marie Antoine de Noailles the same surrender terms. But Noailles refused, saying he had enough supplies for a long siege. So Loring left for Jamaica with his prisoners. He left two ships, Cumberland and HMS Pique, to continue the blockade.

That evening, Noailles tried to escape with six small ships. The British ships saw them on December 5-6. Most of the French ships were captured. Only Noailles's ship escaped. But Noailles was badly wounded and died soon after reaching Havana, Cuba.

The fall of Môle-Saint-Nicolas ended French rule in Saint-Domingue. French troops remained in Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, but they were too few. Dessalines' forces now controlled the western part of the island. Historian Christer Petley said Dessalines became one of the most successful military leaders against Napoleon. On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared the new nation of Haiti. It was the first independent Caribbean nation since ancient times.

Images for kids

-

Scale model of the Duquesne, on display at the Musée de la Marine in Toulon

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |