Bob Marshall (wilderness activist) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bob Marshall

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | January 2, 1901 New York City, US

|

| Died | November 11, 1939 (aged 38) New York City, US

|

| Burial place | Salem Fields Cemetery, Brooklyn |

| Occupation | Forester |

| Employer | Bureau of Indian Affairs; United States Forest Service |

| Known for | Founder, The Wilderness Society |

|

Notable work

|

Arctic Village (1933) |

| Parent(s) | Louis Marshall Florence Lowenstein Marshall |

| Relatives | George Marshall, James Marshall, Ruth (Putey) Marshall |

Robert Marshall (January 2, 1901 – November 11, 1939) was an American forester, writer, and activist. He is best known for helping to start The Wilderness Society in 1935. This group works to protect wild places in the United States.

Bob Marshall loved nature from a young age. He was a keen hiker and climber. He often visited the Adirondack Mountains when he was young. He even became one of the first "Adirondack Forty-Sixers." This means he climbed all 46 of the highest peaks there. He also explored the Brooks Range in northern Alaska. He wrote many articles and books about his adventures. His 1933 book, Arctic Village, became a bestseller.

Marshall earned a PhD in plant physiology, which is the study of how plants work. He became wealthy after his father passed away in 1929. He used his money to fund trips to Alaska and other wild areas. He also held important government jobs. He worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the United States Forest Service. In these roles, he helped create rules to protect large areas of land without roads. Many years after he died, these areas were permanently protected. This happened with the Wilderness Act of 1964.

Marshall believed that wilderness was important for people, not just for nature. He helped create a national group to save wild lands. In 1935, he was a main founder of The Wilderness Society. He also gave most of the money to support the Society in its early years. He was a strong supporter of civil liberties, which are basic rights and freedoms for everyone.

Bob Marshall died in 1939 at age 38. Twenty-five years later, his efforts helped pass the Wilderness Act. This law legally defined wilderness areas in the U.S. It protected about nine million acres of federal land. This land was saved from development, road building, and machines. Today, many people see Marshall as a key figure in the wilderness preservation movement. Places like The Bob Marshall Wilderness in Montana and Mount Marshall in the Adirondacks are named after him.

Contents

Bob Marshall's Early Life and Education

Bob Marshall was born in New York City. He was the third of four children. His father, Louis Marshall, was a famous lawyer and conservationist. He worked to protect nature and fought for the rights of minority groups. The family often visited the Adirondack Mountains every summer. Bob's younger brother, George, described these trips. He said they were a time of "freedom and informality." They enjoyed plants, fresh air, and exploring the woods.

Bob went to the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City. This school encouraged students to think for themselves. It also taught them to care about fairness for all people. From a young age, Bob loved nature. He admired explorers like Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

Exploring the Outdoors

Marshall felt a strong pull to the outdoors. He loved exploring, mapping, and climbing mountains. He kept detailed hiking notebooks. He filled them with photos and facts about his trips. In 1915, he climbed his first Adirondack peak, Ampersand Mountain. He was with his brother George and a family friend, Herb Clark. Clark taught them how to navigate the woods and use boats.

By 1921, Bob and George were the first to climb all 42 Adirondack Mountains. These peaks were thought to be over 4,000 feet tall. In 1924, the three of them became the first "Adirondack Forty-Sixers." This means they climbed all 46 of the highest peaks in the Adirondacks.

After high school, Marshall studied at Columbia University. In 1920, he moved to the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University. He had decided as a teenager that he wanted to be a forester. He once wrote that he "should hate to spend the greater part of my lifetime in a stuffy office." He did well in his studies and was known for being unique.

In the early 1920s, Marshall wanted to promote outdoor activities in the Adirondacks. In 1922, he helped start the Adirondack Mountain Club (ADK). This group builds and maintains trails. It also teaches people about hiking. In 1922, he wrote a guide called The High Peaks of the Adirondacks. He wrote that "it's a great thing these days to leave civilization for a while and return to nature."

In 1924, Marshall graduated from Syracuse with a degree in forestry. He finished fourth in his class. In 1925, he earned a master's degree in forestry from Harvard University.

Working for the Forest Service and Exploring Alaska

Marshall started working for the United States Forest Service in 1925. He worked there until 1928. He hoped to go to Alaska, but he was sent to Montana first. His research focused on how forests grow back after fires. He even helped fight a large fire. This experience taught him about working conditions and natural resources. He began to develop ideas about social fairness.

After leaving the Forest Service in 1928, Marshall studied for his PhD. He went to Johns Hopkins University. The next year, he made his first trip to Alaska. He visited the Koyukuk River and the central Brooks Range. He wanted to study tree growth near the timberline in the Arctic. He stayed for 15 months in the small town of Wiseman, Alaska. He loved the Alaskan wilderness. Marshall was one of the first to explore much of the Brooks Range. He named a pair of mountains "Gates of the Arctic."

In 1929, Bob's father, Louis Marshall, passed away. Bob and his siblings inherited a lot of money. Even though he was wealthy, Marshall kept working. He used his money to support his interests, like The Wilderness Society.

In 1930, Marshall earned his PhD. In February 1930, he published an important essay. It was called "The Problem of the Wilderness." This essay is now famous for defending wilderness preservation. He argued that wilderness was special not just for its beauty. It also gave people a chance for adventure. Marshall wrote: "There is just one hope of repulsing the tyrannical ambition of civilization to conquer every niche on the whole earth. That hope is the organization of spirited people who will fight for the freedom of the wilderness." This article became a powerful call to action.

In July 1930, Marshall and his brother George climbed nine Adirondack High Peaks in one day. This set a new record. In August, Marshall returned to Alaska. He wanted to explore the Brooks Range more. He also studied the people living in Wiseman. He called the village "the happiest civilization of which I have knowledge." He spent over a year exploring and collecting information. From this work, he wrote Arctic Village. This book was a study of life in the wilderness. It was published in 1933 and became a bestseller. Marshall shared the money from the book with the people of Wiseman.

Working for Conservation and the Government

Marshall returned to the East Coast in late 1931. While writing Arctic Village, he also wrote many articles about American forestry. He was worried about deforestation, which is when too many trees are cut down. He also gave speeches about his travels and protecting wilderness.

In 1932, Marshall moved to Washington, D.C.. He took a job helping to reform forest management. He started listing all the remaining roadless areas in the U.S. He urged foresters to set these areas aside as wilderness. During the Great Depression, Marshall believed in socialism. He joined groups that helped unemployed people. He also fought against cuts to science funding. He became chairman of the American Civil Liberties Union chapter in Washington, D.C. He was briefly held for taking part in a protest in 1933.

Marshall also joined the National Parks Association. In 1933, he published The People's Forests. In this book, he argued that public ownership of forests was the best way to protect them.

In August 1933, Marshall became the director of the Forestry Division of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). He held this job for four years. The BIA managed resources on many Native American lands. Marshall pushed hard for wilderness protection. He recommended setting aside 4.8 million acres of Native American lands as "roadless" or "wild" areas. This plan was approved shortly after he left the BIA.

Marshall became more and more concerned about civilization spreading into wild lands. He wrote about how the sounds and smells of nature were being lost. He said they were "drowned in the stench of gasoline."

Founding The Wilderness Society

In 1934, Marshall met with Benton MacKaye, who helped plan the Appalachian Trail. They talked about Marshall's idea for a group dedicated to wilderness preservation. Other foresters, like Bernard Frank, joined them. They sent out an invitation to start a group to "preserve the American Wilderness." They believed that wild areas were "a serious human need rather than a luxury."

On January 21, 1935, they officially announced their new organization. It was called the WILDERNESS SOCIETY. They invited Aldo Leopold to be its first president. Marshall provided most of the money for the Society in its early years. He started with an anonymous donation of $1,000.

Many people believe that before Marshall and The Wilderness Society, there wasn't a strong movement to protect wild areas. T. H. Watkins, who edited the Society's magazine, said that Marshall was "personally responsible for the preservation of more wilderness than any individual in history."

Later Years and Legacy

Marshall's last years were very busy. In May 1937, he became director of the Forest Service's Division of Recreation and Lands. He worked to make national forest recreation available to people with lower incomes. He also fought against unfair barriers for ethnic minorities. He continued to support The Wilderness Society. He also supported groups working for civil rights and social justice.

In August 1938, Marshall took his last trip to Alaska. He explored the Brooks Range further. During this time, a government committee investigated "un-American" activities. They claimed Marshall and others were connected to certain organizations. Marshall was too busy traveling to respond. He visited many states across the country.

In September, two important rules were signed by the Secretary of Agriculture. These "U-Regulations" protected wilderness and wild areas. They prevented road building, logging, and hotels. This made their protected status more secure.

On November 11, 1939, Marshall died suddenly on a train. He was only 38 years old. His death was a shock because he was so young and active. His brother George said, "Bob's death shattered me." Marshall was buried in Salem Fields Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York City.

Marshall's Lasting Impact

Bob Marshall never married. He left almost all of his $1.5 million estate to three causes he cared deeply about. These were wilderness preservation, social fairness, and civil liberties. He set up three trusts in his will. One trust supported education about producing things for use, not just for profit. Another helped protect and advance civil liberties. The third supported "preservation of the wilderness conditions in outdoor America." This became the Robert Marshall Wilderness Fund. He only left money to one person: $10,000 to his old friend and guide, Herb Clark.

Marshall's book, Alaska Wilderness, Exploring the Central Brooks Range, was published after he died in 1956. It helped inspire the creation of Gates of the Arctic National Park. His writings about the Adirondacks were published in 2006. The book is called Bob Marshall in the Adirondacks.

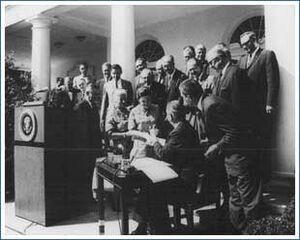

Since it started, The Wilderness Society has helped pass many laws to protect public lands. It has also bought land for preservation. It has contributed to protecting over 109 million acres in the National Wilderness Preservation System. Marshall's dream of permanent wilderness protection came true 25 years after his death. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law on September 3, 1964.

The Wilderness Act was written by Howard Zahniser. He died just four months before the bill was signed. The law allowed the United States Congress to set aside 9 million acres of federal land. These areas would be kept permanently unchanged by humans. It also allowed more land to be designated as wilderness. When defining wilderness, Zahniser used ideas from Marshall and his friends. He said wilderness is "an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." The signing of this act was a huge moment for The Wilderness Society. With this act, the United States promised to protect wild and beautiful natural areas for future generations.

Places Named After Bob Marshall

The Bob Marshall Wilderness is a large area in Montana. It was created in 1964, the same year the Wilderness Act became law. It covers about one million acres. It is one of the best-preserved ecosystems in the world. People call it "The Bob." It is the fifth-largest wilderness area in the lower 48 states. According to the 1964 Wilderness Act, no motorized or mechanical equipment is allowed. This includes bicycles or hang gliders. Camping and fishing are allowed with a permit. But there are no roads, and logging and mining are forbidden. "The Bob" is home to grizzly bears, lynxes, cougars, wolfes, black bears, moose, and elk.

Mount Marshall in the Adirondack Mountains is also named after him. It stands 4,360 feet high. Camp Bob Marshall in the Black Hills and Marshall Lake in Alaska are also named in his honor. In 2008, the Adirondack Council suggested creating the Bob Marshall Great Wilderness. This would be near Cranberry Lake in the western Adirondacks. If successful, it would be the largest wilderness area in the Adirondack Park.

At the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF), there are Bob Marshall Fellowships. These help graduate students and professors research wilderness management. The college also has a student "outing club" named after Marshall. It honors his love for the outdoors. A bronze plaque honoring Bob Marshall is in Marshall Hall at SUNY-ESF. This building is named after his father.

Selected Writings

Articles

- "The Wilderness as a Minority Right", U.S. Forest Service Bulletin (1928)

- "Forest devastation must stop", The Nation (1929)

- "The Problem of the Wilderness", The Scientific Monthly (1930)

- "A Proposed Remedy for Our Forest Illness", Journal of Forestry (1930)

- "The Social Management of American Forests", League for Industrial Democracy (1930)

Books

- Arctic Village. New York: The Literary Guild (1933)

- The People's Forests. [On Forestry in America.]. New York: H. Smith and R. Haas (1933)

- Alaska Wilderness, Exploring the Central Brooks Range (1956)

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |