Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place |

|

|---|---|

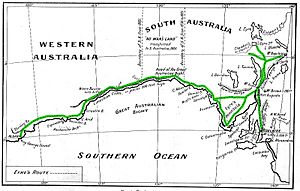

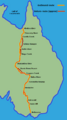

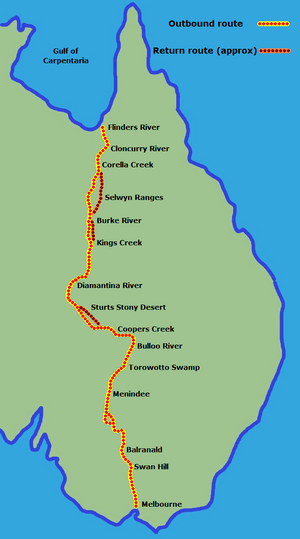

Burke and Wills route

|

|

| Location | Birdsville Track, Innamincka, South Australia |

| Official name: The Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place | |

| Type | Listed place (Historic) |

| Designated | 22 January 2016 |

| Reference no. | 106061 |

The Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place is a special historic area in South Australia. It's found along the Birdsville Track near Innamincka. This place was added to the Australian National Heritage List on January 22, 2016. It's important because it tells the story of early European explorers and the local Aboriginal people who helped them.

Contents

The Story of the Land

The Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks were used by Aboriginal people for thousands of years. They were ancient trails for trade and travel. These paths were not always fixed, sometimes changing over time.

People have lived in Australia's desert regions for a very long time. Some old sites found here are between 12,000 and 15,000 years old. Before Europeans arrived, many Aboriginal language groups lived and traveled through these dry lands.

The Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks cross the lands of many Aboriginal groups. These include the Yandruwandha people, Diyari, Dhirari, Wonkangurru, Ngamini, Gawarawarga, Garanguru, and Yarlijandi. News and goods traveled far across Australia through these traditional routes. Things like red ochre, gypsum for rain ceremonies, tools, and weapons were traded. The rivers and water sources, like Strzelecki Creek and Cooper Creek, were vital for survival.

These routes helped different groups connect and share their culture. They were very important for rituals and ceremonies. Even today, many of these tracks are culturally significant. Later, non-Indigenous people used these same pathways to explore and settle the country. The Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks became important for moving sheep and cattle. They connected the center of Australia to markets in the south.

Early Explorers in Central Australia

In the 1830s and 1840s, explorers like Edward John Eyre and Charles Sturt explored northern South Australia. They were looking for new land for farming animals. Eyre found large salt lakes like Lake Torrens and Lake Eyre. He described the area as a "dreary waste."

Sturt later found the Strzelecki Creek and the Cooper Creek system. But he also thought the region wasn't good for grazing. Despite these early reports, people who raised animals were eager for new land.

In the 1850s, more explorers like Benjamin Herschel Babbage, Augustus Charles Gregory, John McDouall Stuart, and Peter Warburton learned more about the region.

Babbage found permanent waterholes, which made him think the "impassable" salt lakes could be crossed. Gregory's travels also showed that the area could be explored. These discoveries led to more people wanting to settle in the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks region.

By the mid-1800s, Europeans had explored much of Australia. But no one had crossed the continent from south to north. There was a race between South Australia and Victoria to be the first. They also wanted to claim the unclaimed land in northern Australia.

People wondered what was in the center of Australia: a desert, an inland sea, or a big river. Victoria, a smaller colony, wanted to expand its territory. The gold rush had made Victoria wealthy, and its scientific groups wanted to solve the mystery of Australia's center. The Royal Society of Victoria planned a big expedition to cross the continent.

South Australia also wanted to be first. In 1860, John McDouall Stuart set out from Chambers Creek. He traveled north and reached Tennant Creek but had to turn back. In 1861, Stuart tried again, knowing that Burke and Wills were also trying to cross the continent. Stuart was turned back again. But he recovered and launched another expedition. On July 24, 1862, Stuart reached the north coast of Australia. He had found a route from south to north! This was a huge achievement for South Australia and Australia.

The Burke and Wills Expedition (1860-1861)

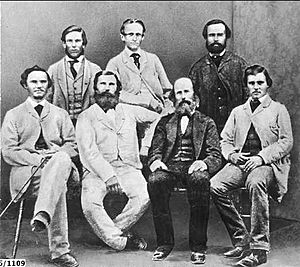

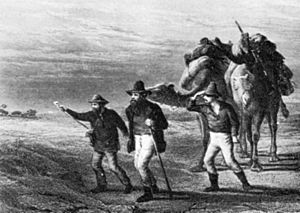

In 1860, the Royal Society of Victoria organized the Victorian Exploring Expedition. It was the most well-equipped exploration party in Australian history. Their goal was to cross Australia and claim new land for Victoria. This expedition was later called the "Burke and Wills Expedition." It included 19 men, 26 camels, 23 horses, and many supply wagons.

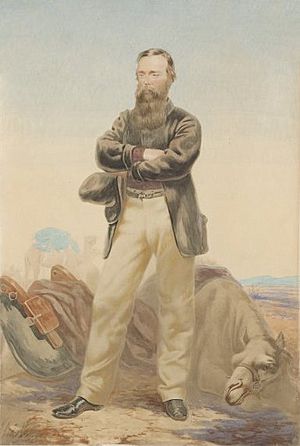

The leader was Robert Burke, an Irish superintendent. He was known for being hot-tempered and not having a good sense of direction. Many people questioned if he was the right choice to lead.

The team included scientists and laborers. William John Wills was the surveyor and observer. He was a talented scientist who loved the Australian outback. His calm nature helped balance Burke's temper. Dr. Hermann Beckler was the medical officer and botanist, and Ludwig Becker was the naturalist.

The expedition started from Royal Park in Melbourne on August 20, 1860. About 15,000 people watched them leave. The party had a lot of equipment, including a large bathtub and an oak table! This made them very slow. It took them 56 days to travel 750 kilometers to Menindee. Along the way, some men were fired or quit. Wills was promoted to second-in-command.

From the start, the expedition relied on Aboriginal guides. These guides helped them find paths and water. They knew the land much better than the explorers.

The Menindee Depot

Burke set up a supply base at Menindee. He told the team there to build a strong depot and wait for his orders. Burke then took an "advanced party" north to find a second supply base. This would help them reach the Gulf of Carpentaria. Burke hired William Wright, an experienced bushman, to guide the rest of the team to Cooper Creek.

Later, two men from the Menindee party, Lyons and McPherson, got lost and ran out of water. An Aboriginal tracker named Dick saved them. He went back to Menindee to get help. Dr. Beckler and another Aboriginal man, Peter, went to find them.

Aboriginal people helped them find Lyons and McPherson. They also shared food like iguana and snake. This brave action by Dick was honored with a portrait and a medal in Melbourne.

The Fort Wills Depot

Burke's advanced party included Wills, John King, and Charles Gray. They set up Fort Wills Depot on November 11. Burke then split the party again. He took Wills, King, and Gray to make the final push to the Gulf of Carpentaria. He left William Brahe in charge of Fort Wills. Brahe was told to wait for three months, or until supplies ran out. Wills secretly told Brahe to wait for four months.

Burke warned Brahe to avoid Aboriginal people. But local Aboriginal people often visited the camp. They exchanged food and goods with the explorers. Brahe and his men stayed at Fort Wills for four months. They built a timber fence to protect their supplies. Brahe sometimes used gunfire to keep Aboriginal people away. But Aboriginal people often tried to connect with the explorers, offering fish and nets.

The Gulf Party

On December 16, 1860, Burke, Wills, King, and Gray left Fort Wills. They had six camels, one horse, and three months of supplies.

Even though Burke wanted to avoid Aboriginal people, his party often relied on their help. Wills noted that a large camp of Aboriginal people gave them fish, which was a "valuable addition to our rations."

Aboriginal people often offered to help the explorers. As they neared the Gulf of Carpentaria, Aboriginal people showed them the best path through boggy ground.

On February 10, 1861, Burke's party reached a tidal channel. They had technically crossed the continent. But they couldn't get through thick mangrove swamps to reach the sea. They were tired and hungry, with only a quarter of their supplies left. The journey back was about survival.

On the way back, Burke had to ration food strictly. The men grew weaker. Animals were killed for food, and equipment was left behind. Gray became ill and died on April 17 from hunger and exhaustion.

The Return to Fort Wills

Brahe and his men at Fort Wills were also struggling with illness and hunger. Brahe left Fort Wills on April 21, believing Burke's party was lost. He buried some supplies near a tree and left a message carved into its trunk.

In an amazing turn of events, Burke, Wills, and King arrived at Fort Wills on the afternoon of April 21. They found the camp empty, just nine hours after Brahe had left! They were too weak to catch up. They found the "Dig Tree" message and the buried supplies.

Burke, Wills, and King discussed what to do next. Wills and King wanted to go back to Menindee. Burke suggested going to Mount Hopeless Station, which was closer. They rested and then headed south. They continued to receive help from Aboriginal people, who gave them fish.

They relied on fish and nardoo, an aquatic fern that could be ground into flour. But this diet didn't give them enough nutrition. They became more and more dependent on the kindness of the Yandruwandha people.

Koorliatto Creek

Meanwhile, William Wright, who was supposed to bring supplies from Menindee to Fort Wills, was delayed. Several members of his party became very ill and died.

At Koorliatto Creek, Aboriginal groups tried to get Wright's party to move on. They even offered to show them the way to find Burke. Wright's party struggled with illness and hostility from some Aboriginal groups.

In late April, Brahe's party met Wright's survivors. They decided to return to Fort Wills. They arrived on May 8 but didn't check the buried supplies or notice any signs that Burke's party had been there.

Burke and Wills' Final Days

As the explorers wandered along Cooper Creek, Wills and King learned from the Yandruwandha people. King even tried to learn their language. But Burke remained suspicious of Aboriginal people.

The harsh conditions and their failing health led to the deaths of Burke and Wills. On June 26, 1861, Wills became very ill. Burke and King went to look for Aboriginal people, as it was their only hope. Burke died around June 30, 1861. King left Burke unburied and went back to Wills, only to find Wills had also died.

King was now alone. He found the local Aboriginal people, and his life depended on them. They showed him great kindness and gave him food. King lived with the Yandruwandha for about three months. He was found by Edwin Welch, a member of a rescue party, on September 15, 1861. King never fully recovered his health and died at age 33.

The Rescue Expeditions

People in Victoria became worried about the missing explorers. Four rescue parties were sent out from different parts of Australia. These expeditions found out what happened to Burke and Wills. They also explored vast new areas of land. They couldn't have done it without the help of Aboriginal people.

- The first rescue party was led by Alfred Howitt from Melbourne.

- The second was led by John McKinlay from Adelaide.

- The third was led by Frederick Walker from Rockhampton.

- The fourth was led by William Landsborough from Brisbane.

These expeditions also looked for new land for grazing animals. They proved that the Cooper Basin and Western Queensland were suitable for this. This led to a big increase in settlement in these areas.

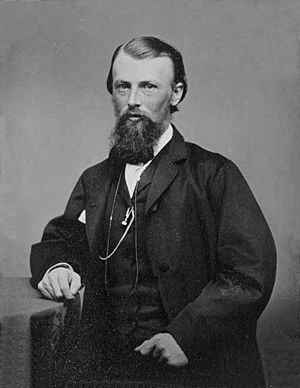

The Victorian Rescue Expedition (Howitt)

Alfred Howitt was an experienced explorer. He reached Cooper Creek quickly, partly because of help from Aboriginal guides like Sandy and Frank. Howitt noted that Aboriginal people helped his group travel through the land. They showed them where to camp and how to find food.

On September 15, 1861, Edwin Welch, a surveyor with Howitt's party, found King living with the Yandruwandha. King was on his knees, praying. Welch was surprised to see a white man among the Aboriginal people. King told him, "I am King, sir, the last man of the exploring expedition."

Howitt's Aboriginal guides quickly shared the news. King was brought back to Howitt's camp. His Aboriginal hosts were happy he was reunited with his friends. King led Howitt to Wills' grave, and then Burke was buried. Howitt made sure to thank the Aboriginal people for their kindness to King and Burke's party.

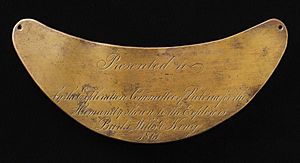

Howitt's diaries showed how much he and King owed to Aboriginal people. He asked for special breastplates to be made. These were inscribed with thanks "for the Humanity shewn to the Explorers Burke, Wills and King 1861." Howitt gave these to the Yandruwandha people later.

Howitt's journals showed how easily he moved through the land with Aboriginal help. This was very different from Burke and Wills' struggles. Howitt's party found King and the bodies of Burke and Wills. His journals show many examples of his positive interactions with Aboriginal communities.

When Howitt returned to Melbourne, he found the hidden journals and maps near the Dig Tree. The tragedy of the expedition made Victorians feel proud and patriotic. King became a hero. Burke was seen as a martyr. Howitt brought the bodies of Burke and Wills back to Melbourne. They received Victoria's first state funeral. About 80% of Melbourne's population attended. A Royal Commission later blamed Burke's leadership and decisions.

The Landsborough Expedition

William Landsborough's party traveled from the Gulf of Carpentaria south to Menindee. They didn't find Burke and Wills. But they successfully traveled a long distance. Aboriginal people like Jemmy, Fisherman, and Jackey guided them and helped them find food and water. Landsborough was criticized for focusing more on finding grazing land than on finding the missing explorers.

The South Australian Burke Rescue Expedition

John McKinlay's party traveled north from South Australia. They found a grave that wasn't an Aboriginal burial site. McKinlay thought it was related to Burke and Wills. He named the site Lake Massacre. He learned from a local Aboriginal man that the person buried there (thought to be Gray) had been killed with an Aboriginal sword. When McKinlay learned that Howitt had already found King and the bodies of Burke and Wills, he focused on finding new grazing land. He discovered large areas suitable for farming animals.

The Victorian Rescue Expedition (Walker)

Fredrick Walker's expedition started from Rockhampton. He found camel tracks near the Flinders River and followed them. But he didn't find any other signs of the missing party.

Cooper Droving and Settlement

The expeditions of Stuart, Burke and Wills, and the rescue parties opened up central Australia. The Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks became important routes for moving sheep and cattle. They connected the center of Australia to markets in the south.

In 1873, John Conrick and Robert Bostock were the first permanent settlers in the region. They set up properties near Innamincka. With the help of local Aboriginal people, Conrick helped establish the Strzelecki Track as a recognized route for moving animals.

Afghan Cameleers

Camels and their handlers, called cameleers, played a big role in developing life along the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks. These cameleers came from places like Afghanistan and India. From the 1860s to the 1920s, thousands of camels and cameleers came to Australia.

Camels were much better than horses for the Australian desert. They could carry heavier loads and needed less water. The first large group of camels in Australia was for the Burke and Wills Expedition. The rescue parties also used camels, which proved how useful they were in the harsh desert.

After the 1920s, trucks and cars became more common. Camels were used less for transport. Some cameleers stayed in Australia, while others returned home.

About the Heritage Site

The Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place covers about 61 hectares. It stretches for about 70 kilometers along Cooper Creek. It includes five important sites:

- Wills' Site

- King's Site

- Burke's Tree

- Howitt's Site (these four are in South Australia)

- The Dig Tree and Fort Wills Site (in Queensland)

The area is mostly dry, but the Cooper Creek system creates wetlands. These wetlands have large trees like River Red Gums.

The Dig Tree and Fort Wills Site

This site is about 60 by 70 meters. It's managed by the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. It has two marked trees, stone markers, and signs. The Dig Tree is a very old Coolabah tree (about 200-250 years old).

Three messages are thought to have been carved into the tree:

- "B LXV" on the creek side (meaning 65th camp from Melbourne).

- "DEC 6.60 APR 21.61" to show when the camp was set up and left.

- A "DIG" message telling Burke, Wills, and King where to find buried supplies. The exact words of this message have been debated for years.

The Face Tree is about 25 meters east of the Dig Tree. It has a carving of Robert O'Hara Burke's face and the letters "ROB." Wooden walkways have been built around these trees to protect them. Fort Wills is part of this larger site.

Howitt's Site

The exact location of Howitt's Site, where he found John King, is debated. The site often shown in books is where Howitt camped in 1862. It's about 40 kilometers from the Dig Tree. A stone marker is at this site.

Burke's Tree

This site is about 9 kilometers northeast of Innamincka. It has a Coolabah tree that marks Burke's original grave. A memorial stone reads "Robert O'Hara Burke died here 28 June 1861." The tree and stone are surrounded by a low fence. John McKinlay carved his initials "MK" and the word "DIG" into the tree in 1861. Over time, floods have raised the ground, and the carvings are no longer visible.

King's Site

King's Site is about 8 kilometers west of Innamincka. It has a stone memorial between two trees. The stone was put up in 1973. It tells the story of John King's rescue by Edwin Welch. In 1948, a nearby tree was carved with the word "KING."

Wills' Site

The exact location of Wills' Site, where William John Wills died, is also debated. The site commonly known is about 20 kilometers west of Innamincka. This is where Howitt's rescue party found and buried Wills' body. The site has a stone memorial, three trees, and a sign. Howitt carved "W J WILLS XLV YDS NNW AH" into a nearby tree. Later, another tree was carved with "WILLS 1861."

Condition of the Sites

These five sites are where dramatic events of Australian exploration happened over 150 years ago. Some original parts have disappeared due to floods or people taking souvenirs. But all five sites are now managed by professionals and protected by state laws.

The Dig Tree and Fort Wills

The Dig Tree is in good condition. It has been treated for pests, and cement was added for stability. The carvings are hard to see now because the tree has grown. Walkways help protect the trees from visitors.

Howitt's Site

This site is generally in good condition.

Burke's Tree

This site is in good condition. The tree looks healthy, but one large branch is resting on the fence. Some pieces of the tree have been removed over the years.

King's Site

This site is generally in good condition. The "KING" carving is visible, but a crack has damaged it.

Wills' Site

Wills' site is generally in good condition. The memorial stone has some water damage, and a tree branch hangs over it.

Why This Place is Important

The Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place is very important to Australia. It's where key events of the Burke and Wills Expedition took place. This expedition was a huge moment in Australia's history. It was the first to cross the continent from south to north. The rescue parties that followed also explored vast areas of the outback.

The expedition helped develop Australia's animal grazing industry. It also changed how Australia's borders were drawn. The story of Burke and Wills shows how Europeans explored Australia in the 1800s. It also shows how they viewed the Australian environment and its Indigenous peoples.

The expedition involved many people and was funded by public donations. Sadly, seven lives were lost, including Burke and Wills. Their story has fascinated Australians for over 150 years. It has become a "national myth of heroic effort" and helped shape Australia's national character.

This heritage place connects us to the main people of the expedition: Robert Burke, William Wills, John King, Alfred Howitt, and the Yandruwandha people who helped them. Burke and Wills were the leaders. Their decisions greatly impacted the expedition. John King was the only survivor of the group that reached the Gulf of Carpentaria. He survived because the Yandruwandha people cared for him. Alfred Howitt rescued King and played a key role in the story. He recorded the names of the Yandruwandha people who treated King like one of their own.

The Burke, Wills, King and Yandruwandha National Heritage Place was added to the Australian National Heritage List on January 22, 2016, because it meets important criteria.

Criterion A: Events, Processes The five sites are the main locations of the Burke and Wills Expedition. This expedition was a turning point that led to a lot of exploration and settlement in the Australian outback. New grazing lands were opened up. The expeditions by Burke and Wills, John McDouall Stuart, and the rescue parties changed Australia's map. They led to South Australia taking over the Northern Territory and Queensland's border moving west.

The expedition happened in Yandruwandha Aboriginal country. It shows how Europeans in the 1800s thought about Aboriginal people. At first, Burke was suspicious of the Yandruwandha. But as their situation got worse, Burke, Wills, and King relied more and more on the Yandruwandha's help. After Burke and Wills died, John King lived with the Yandruwandha until Howitt found him.

The Dig Tree and Fort Wills Site is where much of the expedition's tragedy happened. Burke, Wills, and King returning to the site was a big achievement. But they arrived just hours after their friends had left. The "DIG" carving marked hidden supplies that helped them survive. This site shows a boundary in the outback where Europeans, with limited knowledge, could barely survive.

Burke's Tree and Wills' Site, where they died, show how harsh and dangerous the outback was for Europeans in the 1800s. They remind us of Burke and Wills' roles as leaders.

Howitt's Site shows the efforts of the rescue parties. It's where John King was found. Howitt's success in finding King and exploring new lands highlights the achievements of the rescue teams. Their success was also due to the information and support they got from Aboriginal people like the Yandruwandha.

King's Site is important because it's where King was found alive. King survived because the Yandruwandha people were kind to him. This site is a great reminder of the Yandruwandha people's vital role in this famous Australian story.

Criterion H: Significant people The Burke and Wills Expedition Sites are important because they are linked to Robert Burke, William Wills, John King, Alfred Howitt, and the Yandruwandha people.

The Burke and Wills Expedition is one of Australia's most famous historical events. People are still fascinated by its drama and tragedy. Burke and Wills were at the center of the story. Their decisions, like not leaving a clear message at the Dig Tree, led to many later events. Their expedition has become a national story of struggle and survival.

John King was the only survivor of the small group that reached the north coast. His survival shows how well the Yandruwandha people adapted to their land, which was deadly for the explorers. King's survival also highlights the importance of the rescue parties.

Alfred Howitt was a leading Australian explorer, scientist, and anthropologist. He was key to the Burke and Wills story because he rescued John King and brought the bodies of Burke and Wills back to Melbourne. He represents all the rescue parties that made important discoveries.

The Yandruwandha people were a crucial part of the Burke and Wills expedition on Cooper Creek. Even though the explorers were sometimes cautious, the Yandruwandha were mostly welcoming. They offered fish and nardoo in exchange for small items. After Burke and Wills died, the Yandruwandha took care of King. They also helped the rescue party find King and the bodies of Burke and Wills. Their role is a significant part of Australia's cultural history.

Images for kids