Camp Nelson National Monument facts for kids

|

Camp Nelson National Monument

|

|

Camp Nelson in 2008

|

|

| Location | Jessamine County, Kentucky, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Nicholasville, Kentucky |

| Architect | U.S. Army of the Ohio Eng. Corps; Simpson, Lt.Col. J.H. |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival |

| Website | Camp Nelson National Monument |

| NRHP reference No. | 00000861 (NRHP), 13000286 (NHL) |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | March 15, 2001 |

| Designated NHLD | February 27, 2013 |

| Designated NMON | October 26, 2018 |

Camp Nelson National Monument is a special historical place in Jessamine County, Kentucky. It covers about 525 acres (2.1 km²) and is a national monument, museum, and park. During the American Civil War, it was a very important base for the Union Army.

The camp was set up in 1863. It served as a supply center and a place where new soldiers joined the Union Army. Many of these soldiers were formerly enslaved people who had escaped to fight for freedom. Others came from Eastern Tennessee.

In 2018, President Donald Trump officially made Camp Nelson a National Monument. This means it is now protected and managed by the National Park Service. The American Battlefield Trust also helped save over 380 acres of this historic land.

Contents

Camp Nelson's Beginnings

Camp Nelson was first created to help the Union Army move into Tennessee. It was named after Major General William "Bull" Nelson, who had recently been killed. The camp was built near Hickman Bridge, which was the only bridge over the Kentucky River in that area.

The location was chosen for several reasons. It helped protect the bridge and gave the Union Army a base in central Kentucky. It also helped prepare for securing the Cumberland Gap and eastern Tennessee. The camp was also a training ground for new Union soldiers. The steep cliffs of the Kentucky River and Hickman Creek made the site naturally strong. Only the northern side needed extra defenses against attacks from the Confederate side.

Even with its good location, Camp Nelson had some challenges. When General Ambrose Burnside attacked the Cumberland Gap and Knoxville, Tennessee, the camp's distance and lack of railroads made it hard to get supplies there.

Because of these issues, General William Tecumseh Sherman decided Camp Nelson should focus on training African American soldiers. He pushed for this after General Ulysses S. Grant visited in 1864. Grant had seen how difficult it was to move supplies overland. Despite Grant's concerns, Camp Nelson continued to supply major battles in 1864. It even provided 10,000 horses for the Atlanta Campaign.

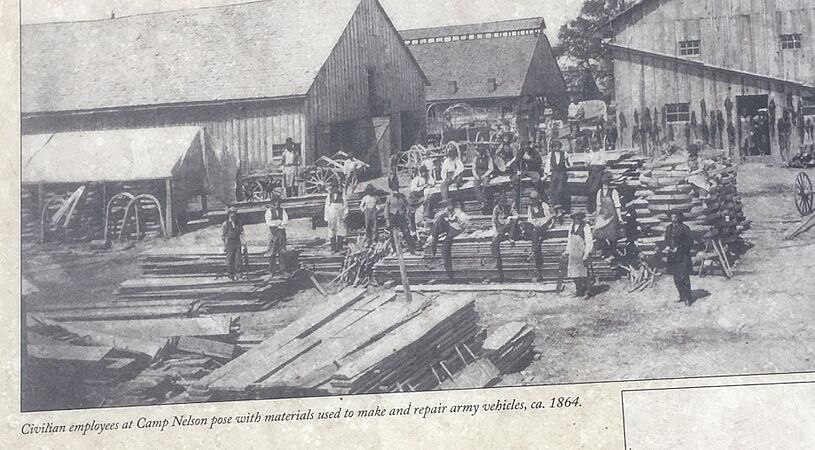

Confederate raider General John Hunt Morgan saw Camp Nelson as a valuable target. Union forces prepared for attacks in 1863 and 1864. In June 1864, civilian workers volunteered to guard the camp's northern defenses. Their efforts helped save the camp from being captured.

African Americans at Camp Nelson

Kentucky was a slaveholding state but did not join the Confederacy. This meant that enslaved people in Kentucky could not be freed by the Emancipation Proclamation at first. However, many African American men and women contributed greatly to the Union war effort. They worked as laborers and later as soldiers.

The Union Army began to use thousands of enslaved men for labor. They were often "impressed," meaning they were required to work for the army. If their owners were loyal to the Union, the owners were paid. If the owners were disloyal or unknown, the enslaved person received wages.

In 1863, General Jeremiah Boyle allowed the army to impress enslaved men aged 16–45 from nearby counties. These men helped build the camp, including railroads, forts, and over 300 buildings. An estimated 3,000 impressed workers were at Camp Nelson in 1863.

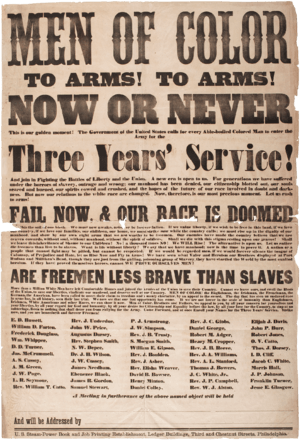

The Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 freed enslaved people only in the states that were rebelling. Since Kentucky was not rebelling, it did not apply there. However, African Americans who joined the Union Army were freed from slavery. Kentucky became the second-largest contributor of U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), with over 23,000 soldiers. Camp Nelson alone trained more than 10,000 of these recruits. Eight USCT regiments were formed there.

In 1864, Kentucky's governor reluctantly agreed to let African American men join the army. At first, their owners had to give permission. But many enslaved men fled to Camp Nelson to enlist anyway. This led to some difficult situations, with some men being sent back to their owners.

By June 1864, owner consent was no longer needed. This made it easier for African Americans to join the Union Army. Large groups of recruits arrived, facing harassment on their way to Camp Nelson. For example, a group from Danville was attacked with stones.

Reverend John Gregg Fee noted that many recruits showed signs of past mistreatment. Despite this, army doctors found most recruits to be healthy and ready to serve.

Refugee Families at Camp Nelson

Families of soldiers and others escaping slavery came to Union camps like Camp Nelson seeking safety. These families were called refugees. At first, the army did not have a clear plan for them. They were allowed to build a small village of shanties at Camp Nelson.

However, several orders were given to make these families leave the camp. They kept returning because they had nowhere else to go. In November 1864, District Commander Speed S. Fry ordered soldiers to force about 400 women and children out of the camp. Their huts were burned, and the weather was freezing. This terrible event led to 102 deaths from cold and sickness.

Chief Quartermaster Theron E. Hall and Reverend John Gregg Fee spoke out against this cruelty. They shared stories of the suffering families. As a result, the military changed its policies. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered that permanent shelter be built for all refugees.

By December 1864, the "Home for Colored Refugees" was built. It included cottages, a dining hall, barracks, a school, and a dormitory. In March 1865, a new law freed the wives and children of USCT soldiers. This caused the refugee population to grow to over 3,000.

The school was run by the American Missionary Association (AMA). It had both white and African American teachers, including E. Belle Mitchell and Reverend Gabriel Burdett. The camp also had a hospital for refugees, but infectious diseases were common. About 1,300 refugees died at Camp Nelson. An obelisk at the refugee cemetery honors their memory.

Battles and Achievements of USCT Soldiers

The 5th and 6th U.S. Colored Cavalry (USCC) from Camp Nelson fought in important battles. These included the Battle of Saltville I and the Battle of Saltville II in Virginia. In Saltville I, in October 1864, the USCC soldiers showed great bravery despite a Union defeat. Sadly, after the battle, some USCC soldiers were attacked and killed. Champ Ferguson was later tried and executed for these actions.

In December 1864, the 5th and 6th USCC returned for the successful second attack on Saltville. They helped destroy the Confederate saltworks and damaged lead mines. These soldiers earned a strong reputation for their courage.

In January 1865, the 5th USCC faced another attack in Simpsonville, Kentucky. While moving cattle, 80 soldiers were ambushed by Confederate guerrillas. Many were killed or wounded.

Other Camp Nelson units, like the 6th USCC and the 114th and 116th Colored Infantry, were part of General Grant's Appomattox campaign. They fought in the siege of Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia. These soldiers were present when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse.

White Refugees from East Tennessee

Many people from eastern Tennessee were loyal to the Union, even though Tennessee was a Confederate state. Thousands of these people, often very poor, came to Camp Nelson for help. They had been driven from their homes and lost their property. The United States Sanitary Commission helped care for them.

Several Union regiments from East Tennessee were trained at Camp Nelson. These included the 8th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry and various cavalry and artillery units.

After the War

After the Civil War, Camp Nelson became a place where formerly enslaved people received their freedom papers. Many considered it their "cradle of freedom." The United States Sanitary Commission also ran a home for soldiers there.

Many USCT soldiers from Camp Nelson went on to achieve great things:

- Angus Augustus Burleigh became a sergeant and later the first black graduate of Berea College. He became a Methodist minister and served as a chaplain.

- Elijah P. Marrs was a sergeant who taught reading at Camp Nelson. After the war, he became a teacher and Baptist minister. He co-founded a college that became Simmons Bible College.

- Peter Bruner wrote his autobiography about his journey to freedom. He became the first African American to work at Miami University in Ohio.

- Gabriel Burdette was an impressed worker who enlisted in the 114th U.S. Colored Infantry. He became a teacher, nurse, and minister, helping refugees. He was also the first African American on the Berea College Board of Trustees.

Camp Nelson Today

Today, 525 acres (2.1 km²) of the original Camp Nelson are preserved as the Camp Nelson National Monument. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a National Historic Landmark District. It is also part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Camp Nelson is unique because its land was never developed for other uses after the war. This means much of its history is still visible.

In 2018, President Trump used the Antiquities Act to make Camp Nelson a National Monument. This transferred its care to the National Park Service.

The Oliver Perry House, built around 1846, is the only original building still standing from the camp. During the war, it was used as officers' quarters and was sometimes called the "White House." It is currently being restored.

The park has five miles of walking trails. Visitors can see remnants of the forts and fortifications with historical signs. Fort Putnam has been rebuilt to look like the original. Re-enactors sometimes fire a Civil War cannon there during special events. The Visitor Center has a film and a museum.

Camp Nelson National Cemetery is nearby. It helps families find records of relatives buried there or who served at the camp.

Stories and Films About Camp Nelson

- Load in Nine Times by Frank X Walker is a book of poetry inspired by his ancestors who enlisted at Camp Nelson. It tells stories through the voices of soldiers, their families, and historical figures.

- The PBS series Secrets of the Dead featured an episode called "The Civil War's Last Massacre." It tells the story of the attack on the 5th USCC in Simpsonville, Kentucky, in January 1865.

Gallery

See also

- List of national monuments of the United States

- African Americans in the Civil War

- Colored Soldiers Monument in Frankfort

- United States Sanitary Commission, photo of Camp Nelson soldiers' home

- 12th Regiment Heavy Artillery U.S. Colored Troops, organized and sometimes stationed at Camp Nelson

- E. Belle Mitchell, first African American educator at Camp Nelson

- 5th United States Colored Cavalry Regiment

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |