Imperial woodpecker facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Imperial woodpecker |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Female (left) and male (right) mounted specimens, Museum Wiesbaden | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Campephilus

|

| Species: |

imperialis

|

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Picus imperialis Gould, 1832 |

|

The imperial woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) is a very large woodpecker that used to live only in Mexico. If it still exists, it is the biggest woodpecker in the world. It could grow to about 56 to 60 centimeters (22 to 24 inches) long. Researchers found that this woodpecker climbed trees slowly. But it flapped its wings very fast compared to other woodpeckers.

Because it looks a lot like the ivory-billed woodpecker (C. principalis), it is sometimes called the Mexican ivory-billed woodpecker. However, this name is also used for another bird, the pale-billed woodpecker (C. guatemalensis). This large and easy-to-spot bird was well known to the native people of Mexico. They had different names for it, like cuauhtotomomi in Nahuatl. The Tepehuán people called it uagam. The Tarahumara people called it cumecócari.

Contents

About the Imperial Woodpecker

What Did It Look Like?

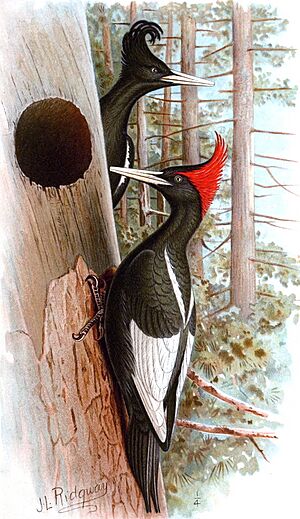

The imperial woodpecker was a very large bird. It was usually between 56 to 60 cm (22 to 24 inches) tall. The male imperial woodpecker had a red crest on the sides, with a black center. Most of its body was black. It had large white patches on its wings. It also had thin white stripes on its back, like "braces." Its bill was huge and ivory-colored.

All of its feathers were black, except for the tips of its inner wing feathers, which were white. Its secondary wing feathers were white. It also had a white stripe on its shoulder. This stripe did not go up to its neck, unlike the ivory-billed woodpecker. The female looked similar to the male. But her crest was all black and curved backward at the top. It did not have any red.

This woodpecker was much bigger than any other woodpecker in its area. It was the only one with completely black underparts. People said its voice sounded like a toy trumpet.

Where Did It Live?

The imperial woodpecker was once found in many places. Until the early 1950s, it was quite common in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains of Mexico. Its range stretched from western Sonora and Chihuahua down to Jalisco and Michoacán. It is thought that in the past, the woodpecker's home range went north into Arizona. But by the time scientists described it in the 1800s, it was only found in Mexico. There have been suggestions it might have lived in Arizona. There is also a possible sighting from 1958 in Big Bend National Park, Texas. However, this is not officially confirmed.

What Was Its Habitat Like?

The imperial woodpecker liked open montane forests. These forests were made up of different kinds of pine trees. These included Durango pine, Mexican white pine, loblolly pine, and Montezuma pine. It also lived among oak trees. These forests were usually found between 2,100 and 2,700 meters (6,900 and 8,900 feet) above sea level. Most records show them living at elevations from 1,920 to 3,050 meters (6,300 to 10,000 feet). But some records show them as low as 1,675 meters (5,500 feet).

What Did It Eat?

The imperial woodpecker mainly ate insect larvae. These larvae were found under the bark of dead pine trees. There are many reports of groups of more than four woodpeckers feeding together. This group behavior might be because of how they found their food.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Breeding has been recorded between February and June. It is likely that one to four eggs were laid. A pair of imperial woodpeckers needed a very large area of untouched, old forest to survive. This area was about 26 square kilometers (10 square miles). Outside the breeding season, the birds were reported to form small groups. These groups could have up to 12 individuals. They would move around a wide area. They seemed to move based on where food was available.

The main food source, beetle larvae in dead trees, was probably found in patches. These patches would only be good for a short time. So, feeding sites were probably best used by "nomadic" groups. If they worked in groups of seven or eight birds, the smallest area of old-growth forest needed for a group was 98 square kilometers (38 square miles).

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology has released a film of the imperial woodpecker. It was recorded in Mexico in 1956.

Decline and Probable Extinction

The imperial woodpecker is officially listed as "critically endangered (possibly extinct)" by the IUCN and BirdLife International. It was not always a rare bird in its suitable habitat. But the total population probably never had more than 8,000 birds. Any remaining population is thought to be very small. This is because there have been no confirmed sightings since 1956. Studies of the remaining habitats show that no areas are large enough to support the species.

The last confirmed sighting was from Durango in 1956. The species is very likely now extinct. If they have gone extinct, it would be because their habitat was destroyed and broken up. Hunting also played a part. These reasons explain why the species has not been seen in over 60 years. However, there have been local reports of sightings.

Researchers believe their decline also sped up because of efforts to get rid of them. Logging companies encouraged people to kill them. They were also over-hunted for use in folk medicine. Their young were considered a special food by the Tarahumara people. People hunted them for sport, food, and medicine for a long time. Their feathers and bills were reportedly used in rituals by the Tepheuana and Huichol tribes. Also, imperial woodpeckers are stunning birds. As they became rarer, many were shot by people who had never seen such a bird and wanted a closer look.

The imperial woodpecker lived mostly in coniferous forests. These forests were at elevations of 2,700-2,900 meters (8,900-9,500 feet). The areas where they lived had many large dead trees. Removing these trees might be linked to their extinction. By 2010, these areas had been cleared and logged many times.

More effort in conservation biology is now focused on studying extinction risk. They also search for rare species that have not been seen for a long time. There are a few recent, unconfirmed sightings. The most recent ones happened after the supposed rediscovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker in 2005.

Researchers Martjan Lammertink and others (1996) looked at many reports after 1956. They concluded that the species did survive into the 1990s in the middle of its range. But they also think it is very unlikely to still be alive. They believe the population was always small in historic times. However, the species was at its highest numbers before a huge decline in the 1950s. The lack of good records from that time was probably due to a lack of research. But this seemed to change quickly just ten years later.

Field research by Tim Gallagher and Martjan Lammertink found important information. This was reported in Gallagher's 2013 book. They talked to elderly people who lived in the bird's range. These people had seen imperial woodpeckers decades earlier. They told the researchers that foresters working with Mexican logging companies in the 1950s told local people that the woodpeckers were harming valuable timber. They encouraged people to kill the birds. As part of this, the foresters gave local residents poison. They told them to put it on trees where the birds fed.

Groups of imperial woodpeckers often fed on one huge, dead, old pine tree for up to two weeks. Putting poison on such a tree would be a good way to wipe out a group of up to a dozen of these large woodpeckers. It might even kill later groups of birds that moved into the area and were attracted to the same tree. Gallagher thinks that such a poisoning campaign might be the main reason for the species' sudden population crash in the 1950s. Before this, there was no clear explanation. A poisoning campaign could have killed entire groups of the bird very quickly. The idea that the woodpeckers were destroying valuable timber was not true. Imperial woodpeckers do not feed on or make holes in live, healthy trees.

A search of an online database called VertNet shows that only 144 physical specimens of the imperial woodpecker exist. This includes only three complete skeletons. A woodpecker skeleton from the Natural History Museum at Tring also seems to belong to this species. The species is also known from a single amateur film from 1956. This film shows one bird climbing, looking for food, and flying. The film has been restored and released by Cornell University. Gallagher was inspired to search for the imperial woodpecker after seeing this 1956 film. It was taken by a dentist named William Rhein, who made several trips to Mexico to find the imperial woodpecker. This is the only known photographic record of the species.

The Government of Mexico has considered the imperial woodpecker to be extinct since 2001. However, if it were rediscovered or brought back, it would immediately get legal protection.

See also