Castalian Springs Mound Site facts for kids

|

|

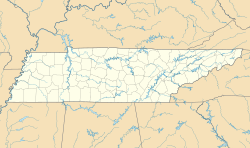

| Location | Castalian Springs, Tennessee, Sumner County, Tennessee, |

|---|---|

| Region | Sumner County, Tennessee |

| Coordinates | 36°23′54.96″N 86°18′48.60″W / 36.3986000°N 86.3135000°W |

| History | |

| Founded | 1100 CE |

| Abandoned | 1450 |

| Cultures | Mississippian culture |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1891, 1893, 1916-1917, 2005-2011, |

| Archaeologists | William E. Myer, Kevin E. Smith |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Platform mounds, burial mound, palisade, plaza |

| Responsible body: State of Tennessee | |

The Castalian Springs Mound State Historic Site is an important Mississippian culture archaeological site. It is also known as Bledsoe's Lick Mound and Cheskiki Mound. You can find it near Castalian Springs in Sumner County, Tennessee.

Archaeologists first explored the site in the 1890s. More recently, Dr. Kevin E. Smith led digs there from 2005 to 2011. Many cool things have been found here. These include special stone statues and a unique shell necklace called the Castalian Springs shell gorget. This gorget is now kept at the National Museum of the American Indian. The State of Tennessee owns this site. It is managed by the Bledsoe's Lick Association for the Tennessee Historical Commission. Right now, the site is not open to the public.

Contents

What Was the Castalian Springs Site Like?

The Castalian Springs site was one of the biggest Mississippian mound centers. It sits on a flat area near a creek that flows into the Cumberland River. People lived here from about 1100 to 1450 CE. The main time of activity was between 1200 and 1325 CE.

The village was surrounded by a palisade, which was a strong wooden fence. The whole area, including the village and nearby homes, was about 40 acres (0.16 square kilometers). It had about a dozen platform mounds. These were flat-topped mounds used for buildings or ceremonies. There was also a burial mound, a large open area called a plaza, and many homes and public buildings.

Early Descriptions of the Site

In the early 1820s, Ralph E.W. Earl first wrote about the site. He dug around quite a bit. He described a low earthen wall with raised earthen towers. This was what was left of the wooden palisade. It enclosed about 16 acres (0.065 square kilometers).

Earl also described the main mound, called Mound 2. It was a huge rectangular platform. It was about 600 feet (183 meters) long and 200 feet (61 meters) wide. It stood 13 to 15 feet (4 to 4.6 meters) high. On its western end was a cone-shaped mound with a flat top. This part was about 18 to 20 feet (5.5 to 6.1 meters) tall.

South of the main mound was a plaza. On its eastern side was a burial mound (Mound 1). This mound was 120 feet (37 meters) across and 8 feet (2.4 meters) tall. On the western side of the plaza was another large platform mound (Mound 3). Outside the palisade, near Lick Creek, was a stone mound (Mound 4). It was 60 feet (18 meters) across and 5.5 feet (1.7 meters) tall. Similar stone mounds have been found at other sites like Beasley Mounds.

What Remains Today?

Over the years, farmers have plowed the area. Because of this, most of the original mounds and the palisade are no longer visible. Only the main platform mound and a few raised areas can still be seen.

Archaeologists have also found stone box graves. These are graves made from stone slabs. They have also found burial caves and other features linked to the site. The area has many small caves because of its karst terrain. One cave, called the "Cave of the Skulls," is near the site. William E. Myer explored this cave during his excavations.

Digging Up the Past: Excavations

In the early 1890s and again in 1916-1917, an amateur archaeologist named William E. Myer explored the site. He later became a "special archeologist" for the Smithsonian. Myer dug up parts of the site, including the stone box graves. He also excavated the large burial mound. This mound held more than a hundred graves.

Myer found several artifacts with special designs. These designs are part of something called the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (S.E.C.C.). Many of these were shell gorgets, which are carved shell ornaments. The Museum of the American Indian acquired these in 1926.

Modern Excavations

The State of Tennessee bought the site in 2005. After that, modern archaeological digs began. Dr. Kevin E. Smith from Middle Tennessee State University led a field school here from 2005 to 2011.

The Castalian Springs Archaeological Project is a long-term research effort. It is supported by Middle Tennessee State University, the Bledsoe's Lick Historical Association, and the Tennessee Division of Archaeology. Their goals include:

- Understanding the size and layout of the site.

- Creating trails and facilities without harming the archaeological remains.

- Training university students in archaeology.

- Teaching the public about the importance of archaeological research.

Amazing Discoveries at Castalian Springs

Many Mississippian stone statues have been found at the site. The first mention of a statue here was before 1823. Since then, several more have been discovered. Some were found in the main mound, and others in nearby village areas.

The Etched Stone Tablet

In 1892, Myer found an etched stone tablet at the site. This limestone tablet is 9 inches (23 cm) by 12 inches (30 cm). It has symbolic images linked to the S.E.C.C.. It shows the upper body of a human figure dressed like a bird of prey. There is a sun symbol on its chest. This image is very similar to the "falcon dancer" found on Mississippian copper plates across the Midwest and Southeast. This tablet was only the second of six such tablets found in Central Tennessee.

Another famous engraved stone, the Thruston tablet, was found nearby in 1878. It was discovered on the banks of Rocky Creek in what is now Trousdale County, Tennessee. This tablet is 19 inches (48 cm) wide by 14 inches (36 cm) tall and 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick. Both sides show many figures dressed in S.E.C.C. clothing. It is named after Gates P. Thruston, a lawyer who became an archaeologist. He explored many sites and collected artifacts. The tablet is now at the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville.

Shell Gorgets

Myer also found over thirty engraved shell gorgets. Several of these are now at the National Museum of the American Indian. The most important gorget is carved in a style called Eddyville or Braden style. This style is thought to be connected to the Cahokia city near Collinsville, Illinois.

This special gorget shows a warrior holding a ceremonial mace. The figure also has unique symbols like the Forked Eye Surround Motif and the Bi-Lobed Arrow Motif. These are all linked to the S.E.C.C. Falcon dancer. Even though the design often shows the figure standing upright, holes in the gorget show it was meant to hang sideways. We don't know yet what this might mean. The collection also included two Cox style and two Nashville I style gorgets.

In 2005, a crew replacing a waterline found a complete Cox style gorget. It was carved from dark gray shale. This is rare because Cox style designs are usually on marine shells. The Castalian Springs site is also one of only three places in Middle Tennessee where "Angel negative painted" ceramic pieces have been found. This type of Mississippian culture pottery is usually found at Angel Phase sites along the Ohio River.

Images for kids

-

Engraved limestone tablet featuring a Falcon dancer

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |