Chetro Ketl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chetro Ketl |

|

|---|---|

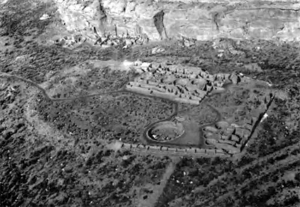

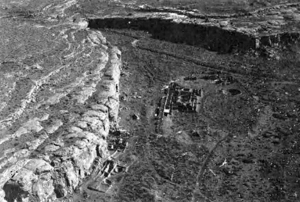

Aerial view from the south

|

|

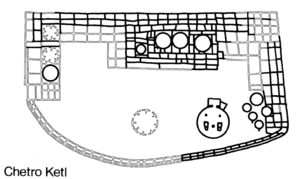

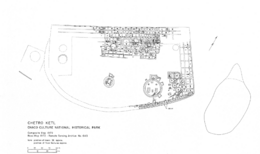

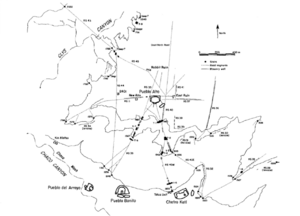

Site map (darker lines denote excavated areas)

|

|

| Location | Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico, United States |

| Nearest city | Gallup, New Mexico |

| Area | 3 acres (1.2 ha) |

| Elevation | 6,000 feet (1,800 m) |

| Built | 945–1070 |

| Architectural style(s) | Ancestral Puebloan |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

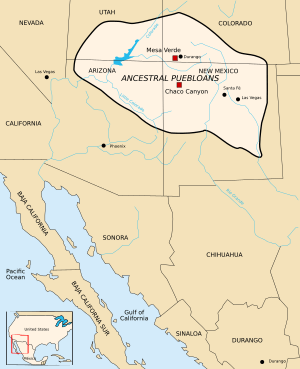

Chetro Ketl is an ancient building and archaeological site. It was built by the Ancestral Puebloans, a group of Native American people. You can find it in Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico, USA.

Building Chetro Ketl started around 990 CE and was mostly finished by 1075 CE. Some parts were changed and updated in the early 1110s. Around 1140, a big drought hit the area. Most of the Chacoan people left the canyon because of this. By 1250, the last people living at Chetro Ketl had moved out.

A Mexican governor named José Antonio Vizcarra found the great house again in 1823. Later, in 1849, a US Army officer, Lieutenant James Simpson, wrote about the large ruins in Chaco Canyon. Edgar Lee Hewett, a famous archaeologist, led digs at Chetro Ketl in the 1920s and 1930s.

Experts think it took over 500,000 hours of work to build Chetro Ketl. They also believe 26,000 trees and 50 million sandstone blocks were used. The building is shaped like a "D". Its east wall is 280 feet (85 meters) long, and the north wall is over 450 feet (140 meters) long. The whole building covers almost 3 acres. Chetro Ketl was the biggest great house in Chaco Canyon by size. It had about 400 rooms.

Chetro Ketl is very close to another important site called Pueblo Bonito. Archaeologists call this area "downtown Chaco." They think it might have been a special, sacred place for the ancient people. Chetro Ketl has unique parts, like a colonnade (a row of columns) and a tower kiva. These features might show influences from Mesoamerica (areas like Mexico and Central America).

No one is completely sure what Chetro Ketl was used for. Many archaeologists think it was a place for big ceremonies. It might have been where priests lived. During special events, people from other communities might have visited. Some experts, like Stephen H. Lekson, believe Chetro Ketl was a palace for Chacoan royalty. He thinks its huge size was meant to impress visitors. The building has worn down a lot since it was found again. This means it's getting harder to learn new things about the Chacoan culture from it.

Contents

The Chacoan People and Their History

Early Life in Chaco Canyon

Long ago in the north, below from the Place of Emergence, everybody came out. Now when those who are everyone's chiefs came out they all went out. They went down south ... They went along coming from the north, and they began to make towns.

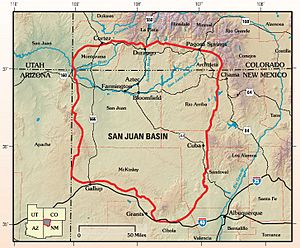

Thousands of years ago, the San Juan Basin area was home to early people. These were hunter-gatherers, meaning they hunted animals and collected plants for food. Around 6,000 BCE, a group called the Oshara tradition lived here. They hunted animals like jackrabbits.

Later, around 1800 BCE, people started growing maize (corn). They also began to gather in larger groups. This led to the development of the Basketmaker culture around 200 BCE. More rain helped them farm better and build permanent homes.

By 1 CE, people were living in pit-houses. These were homes dug partly into the ground. Around the 4th century, people started making pottery. This was a big change for cooking, especially for corn and beans. The bow and arrow also became common around this time.

Growing Communities and Farming

From the 5th to 8th centuries, there was a lot of rain. This helped pit-house communities grow. By the 6th century, people started settling in lower areas, including Chaco Canyon. They became more focused on farming instead of just hunting and gathering. This period is known as Basketmaker III Era. By 500 CE, at least two settlements were in Chaco Canyon. One early site, Shabik'eshchee Village, was lived in until the early 8th century.

As farming improved in the 8th century, areas with good water became crowded. People needed places to store their crops. This led to the first large buildings above ground. This was the start of the pueblos. By 800 CE, farming was essential for survival. This time is called the Pueblo I Period.

By the early 900s, large pit-house settlements were replaced by new building styles. These new styles became the basis for the huge Ancestral Puebloan great houses. This marks the start of the Bonito Phase. Many people moved to Chaco from the San Juan River area. Over time, the Chacoans developed a unique and important society.

Where is Chetro Ketl?

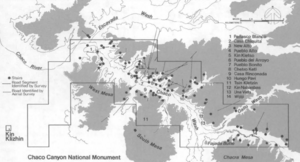

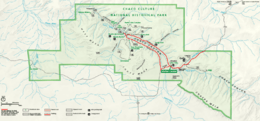

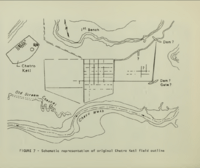

Chaco Canyon is in northwestern New Mexico. It's about 60 miles north of Interstate 40. The land around it is high desert, about 6,000 feet high. Most of the Chacoan sites are at the bottom of the canyon. But some ruins are outside the main canyon.

Chetro Ketl is about 0.4 miles east of Pueblo Bonito. Archaeologists call this area "downtown Chaco." They think a low stone wall might have marked this area as sacred. Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito are placed in a balanced way. They are the same distance from a line that runs north-south across the canyon.

Some researchers believe many great houses in Chaco Canyon were built to line up with the stars or moon. For example, during a minor lunar standstill, the full moon rises along Chetro Ketl's back wall.

Chetro Ketl is across from a large opening in the canyon called South Gap. This spot helped the building get a lot of sun. It also made it easier to see and reach from the south. The back wall of Chetro Ketl is close to the cliffs. This helped the building stay warm from the sun's energy stored in the rocks.

How Chetro Ketl Was Built

Like other great houses in Chaco Canyon, Chetro Ketl was built over a long time. The Ancestral Puebloans dug out huge amounts of sandstone from the cliffs nearby. The period from 1030 to 1130 was a "golden century" for Chaco. During this time, many great houses were built or expanded.

Trees for Building

In 1983, scientists studied wood samples from Chetro Ketl. They learned what kinds of trees were used and when they were cut. They also estimated how many trees were needed. Trees were cut for Chetro Ketl every year. This was different from other sites where trees were cut only sometimes.

Most trees were cut in the spring and early summer. This might mean that some Chacoan groups focused only on cutting trees. They would do this even when others were busy farming.

The most common tree used was the ponderosa pine. About 16,000 of these trees were cut for Chetro Ketl. Now, there are no ponderosa pines left in the canyon. Archaeologists think the trees were cut far away. Then, they were carried, not dragged, back to Chaco Canyon.

Studies show that after 974 CE, most building timbers came from the Chuska Mountains and Mount Taylor. Both are about 47 miles away. This suggests that connections between communities were more important than just how close the trees were.

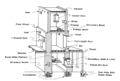

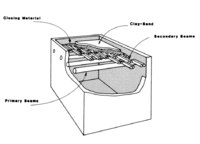

Almost 78% of the 26,000 trees used for Chetro Ketl were cut between 1030 and 1060. Over 7,000 trees were used just for the round rooms called kivas. About 750 trees were used for the great kiva. Roofs were made of large beams, smaller beams, and layers of split wood. Other tools like digging sticks and hammerstones were also used. Many hammerstones have been found inside the walls.

Stone and Mortar

Chetro Ketl's walls were built with stone, clay-sand, and water. Two types of sandstone were used. A hard, gray-brown stone was preferred because it was easier to shape. A softer, tan stone from the cliffs was also used, especially after the harder stone ran out.

The Chacoans made mud mortar from clay or clay-sand and water. They got these materials from the canyon. Water was scarce, so building probably happened mostly during the rainy season. Water was also collected from small pools and deep wells.

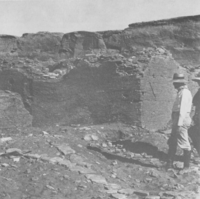

Building Walls (Masonry)

Only skilled Chacoans shaped and set the stones. Others carried supplies and mixed mortar. The thickness of a wall depended on its location. Lower walls were wider than upper ones. Chacoan walls are known for their "core-and-veneer" style. This means they had two outer faces with a core of rubble in between. The strength came from how well the stones in the faces touched each other.

The outer faces of the walls were very detailed. The spaces between stones were filled with small chips of stone or mud mortar. Different patterns of stone showed different building styles or groups of builders. Good wall faces meant less repair work and stronger walls.

Doors and vents often had flat stone sills and wooden beams above them. Chacoan builders also put horizontal logs inside the walls. These "intramural beams" helped make the walls stronger. Inside walls were often covered with a rock veneer. Chetro Ketl's interior walls, especially in the eastern part, had very smooth sandstone with little mortar showing.

Building Stages

In 1934, Florence Hawley used tree rings and wall styles to figure out Chetro Ketl's building history. She found three main periods. The first was 945–1030, but not much from this time is still visible. The second was 1030–1090, when most of the building was constructed. The third was 1100–1116, when existing parts were updated.

Later studies mostly agreed with Hawley's findings. They believe Chetro Ketl was mostly finished by 1075. Building continued until the mid-1110s, when the great kiva was updated.

The second building period (1030–1075) included adding upper stories to the main room block. After 1075, smaller additions were made. Some later parts, including large kivas, used a different stone style called McElmo. This stone was softer and lighter in color. It's estimated that Chetro Ketl needed 50 million sandstone blocks and over 500,000 hours of work to be completed.

McElmo Style

The McElmo Phase was a time in the late 1000s and early 1100s. New pottery and wall-building styles appeared in Chaco Canyon. People started using black-on-white pottery. The way great houses were built also changed.

At first, archaeologists thought the McElmo style came from people moving from Mesa Verde. But later research suggests it developed locally. McElmo pottery was common at Chetro Ketl. The McElmo wall style was used in later additions to the building.

Why Chetro Ketl Was Left Behind

They didn't abandon this place. It is still occupied. We can still pray to the spirits living in these places from as far away as our pueblo. The spirits are everywhere. Not just the spirits of our ancestors, but tree spirits and rock spirits. If you believe that everything has a spirit, you will think twice before harming anything.

The Ancestral Puebloans needed regular rain for their farms. This was always a challenge in Chaco Canyon. By 1130, the rains decreased, and corn crops started to fail. The region suffered from a severe, 50-year drought.

After living there for over 600 years, the Chacoans began to leave the canyon. By 1140, many experts say "Chaco was finished." A study of ancient burials showed that many people, especially children, died young during the drought.

The turning point was a very dry period from 1090 to 1095. More people left Chaco Canyon then. New Puebloan buildings started to grow in other places like Mesa Verde and Aztec. Even though many people left, Chetro Ketl's great kiva might have been used until the early 1200s. Old pottery pieces show that the last people left Chetro Ketl by 1250.

Finding Chetro Ketl Again

After the Ancestral Puebloans left, other groups moved into the area. The Navajo people arrived in the 1400s. In the 1700s, Spanish explorers came from the south. The Spanish explored parts of the region, but there's no record of them finding Chaco Canyon.

In 1823, the governor of New Mexico, José Antonio Vizcarra, found ancient ruins in the canyon. This was the first time outsiders recorded seeing the Chacoan great houses. In 1844, Josiah Gregg wrote the first published mention of Chaco Canyon in his book.

After the Mexican-American War (1846–48), the United States began exploring the area. In 1849, Lieutenant James Simpson of the US Army was very interested in the ruins. He explored the canyon with a group, including the governor of Jemez Pueblo, Francisco Hosta.

Simpson was impressed by Chetro Ketl's walls. He described them as showing a higher level of skill than anything seen from Mexicans or Pueblos at that time. Simpson's group mapped the ruins, took measurements, and sketched the main buildings. They noted the round rooms (kivas) were "sunk in the ground." Simpson explored Chetro Ketl briefly, counting 6 round rooms and 124 ground-floor rooms. He saw one room where the plaster was still on the stone walls. Simpson's report from 1850 is considered the start of Chacoan archaeology.

The scientific study of Chaco Canyon truly began when Richard Wetherill started exploring in 1895. He was famous for finding large Ancestral Puebloan homes in Mesa Verde. He began full-scale excavations at Pueblo Bonito in 1896.

What Does "Chetro Ketl" Mean?

The real meaning of "Chetro Ketl" is not known. Most Chacoan ruins have Spanish or Navajo names, but "Chetro Ketl" is neither. A Mexican guide in 1849 translated it as "rain town." In 1889, a Navajo historian said that in Navajo stories, the building is called Kintyél or Kintyéli, meaning "broad-house." Other Navajo meanings include "house in the corner" and "shining house."

Archaeological Digs at Chetro Ketl

The first official dig at Chetro Ketl was in 1920 and 1921. It was led by Edgar Lee Hewett, who ran Chaco Canyon's first archaeology school. He had visited the canyon in 1902. His plans for digs were delayed by World War I.

Hewett stopped his research when Neil Judd excavated Pueblo Bonito (1924–27). But Hewett returned to Chetro Ketl in 1929 with students from the University of New Mexico. He studied the canyon until 1935. Many Chaco scholars worked with him. Hewett's methods have been criticized, and he never published a detailed report on his work at Chetro Ketl. However, his students' writings tell us a lot about his studies.

Florence Hawley started working with Hewett in 1929. She focused on dating things using tree rings and pottery. She dug in Chetro Ketl's trash mound for two summers. She showed that charcoal from the mound could be used for tree-ring dating. Her 1933 paper explained that the mound's layers were mixed up. Older trash was sometimes put on top of newer trash. This meant newer material was at the bottom and older material at the top. Later digs showed the mound was from more than just daily waste. It had layers from large feasts where pottery was ritually broken. Hawley's work greatly helped in dating Chacoan culture.

In 1921, Hewett dug in Chetro Ketl's great kiva. He found an even older kiva buried 12 feet below. He also found macaw feathers. But he didn't find copper bells, which were common at Pueblo Bonito. Hewett was surprised by the lack of fancy items. No human burials have been found at Chetro Ketl.

In 1931 and 1932, researchers found hidden stashes of turquoise beads and pendants in the great kiva. Over 17,000 beads were found. In 1947, floods threatened Chetro Ketl. Gordon Vivian saved wooden artifacts from an undug room. These wooden figures, some shaped like birds, are very rare. Several stone necklaces were also found. These items show that Chetro Ketl was a place of intense ceremonial activity.

Archaeologists found minerals used for paint pigments at Chetro Ketl. These included charcoal, shale, and colorful stones like malachite and azurite. Twined sandals and bones from hawks and owls were also found. The lack of many exotic items like shells or copper bells might mean Chetro Ketl was less important than Pueblo Bonito. Since Chetro Ketl has only been partly dug up, it's hard to be sure.

Lost Artifacts

Archaeologist Stephen Lekson calls Chetro Ketl "notoriously sterile," meaning few artifacts were found. He says it's hard to know how much material was recovered. Field notes mention baskets, sandals, painted wood, digging sticks, arrowheads, and broken pots. But most of these items are now missing. Lekson believes this is because Hewett didn't handle the collection carefully. The Museum of New Mexico has some items from Chetro Ketl. These include turquoise pieces, a pottery canteen, and a 14-foot-long stone and shell necklace.

What Chetro Ketl Looks Like

Chetro Ketl had about 400 rooms. It was the largest great house in Chaco Canyon. Parts of it were four stories tall, and three stories still remain. The building covers almost 3 acres. About half of this area is an enclosed plaza (open space). The plaza was surrounded by wings of rooms to the north, east, and west. The total length around Chetro Ketl is 1,540 feet. Its east wall is 280 feet long, and the north wall is over 450 feet long. Rooms were built three deep and three or four stories high. The ground level facing the plaza was one story tall.

Chetro Ketl had twelve kivas (round rooms). Two large ones were in the west wing plaza, including a great kiva. Ten more were in the central room block, including a tower kiva. The trash mound was 205 feet long, 120 feet wide, and 20 feet tall. It held a huge amount of debris. Chetro Ketl's plaza is raised 5.75 feet above the surrounding land. This is unique, as other great house plazas are level with the ground.

At the front of the building is a mysterious feature called "the moat." It's two parallel walls that form a long, narrow space. It seems to have been filled in around 1070, when the plaza was raised. Its original purpose is unknown. Tunnels between rooms are found in other Puebloan sites, so it might have helped people move between Chetro Ketl's wings.

A narrow opening on the north wall suggests there was an ancient balcony. Some rooms at the back of the building don't connect directly to the main part. These might have been used for community storage. Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito are the only great houses in Chaco Canyon with corner doorways.

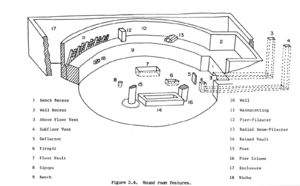

The Great Kiva

Great kivas are much bigger and deeper than regular Chaco-style kivas. Great kiva walls always rise above the ground, while Chaco-style kivas are level with the ground. Chaco-style kivas are often built into the main buildings. But great kivas are always separate. Great kivas usually have a bench around the inside. They also have floor vaults, which might have been used as foot drums for dancers.

Chetro Ketl's great kiva is 62.5 feet across. It is special because it's inside the pueblo's walls. The oldest floor is 15 feet below the current plaza. The current floor is about 9.25 feet below. Several smaller rooms were next to the great kiva. A smaller round room, the Court Kiva, is nearby. It started as a Chaco-style kiva but was later changed to be more like a great kiva.

The outer walls of the great kiva are 2.5 to 3 feet thick. They were built between 1062 and 1090. An antechamber (a small room before a larger one) is attached to the north end. A stairway with nine steps led down from it to the kiva floor.

The great kiva's roof was likely flat, not domed like smaller kivas. It was held up by four large posts and beams. The space between the floor and roof was probably only 5 to 6 feet high.

Thirty-nine small crypts (storage spaces) have been found in the great kiva. They are about 1 foot high and spaced 5.3 feet apart around the inner wall. Their purpose is unknown. They might have been shelves or special altars. A large bench, 3.33 feet wide and 2.75 feet tall, goes around the inside. A firebox was located south of the kiva's center.

The Colonnade

Chetro Ketl has a colonnade, which is a row of columns. This feature is very noticeable and unique in Chaco Canyon. It's also rare in all Ancestral Puebloan buildings. The closest similar structure is far away in Mexico. The colonnade was built after 1105. It was 93 feet long and had thirteen columns. It was later filled in with stone to create more living space.

Some experts believe this feature shows influence from Mesoamerica. They think ideas might have traveled through traders. The colonnade might be a local version of Mexican designs, changed to fit local materials and building methods.

Farming and Pottery

Chaco Canyon gets water from winter storms and summer rains. The Chaco Wash is a deep stream that drains water from the canyon floor. Farming terraces on the mesa behind Chetro Ketl might have been used for special crops like tobacco. Canals from Pueblo Bonito to Chetro Ketl probably carried rainwater. Chetro Ketl's location helped with farming because summer storms often stayed in the South Gap, bringing moisture to the area.

In 1929, Charles Lindbergh took aerial photos that showed a rectangular plot near Chetro Ketl. In the 1970s, the National Park Service used special equipment to study the area. They found a clear grid pattern, suggesting a farm field. This field was about 50 by 65 feet.

Experts believe the Chetro Ketl field is a great example of Chacoan farming. About 20 acres of land were divided into 42 plots. These plots had irrigation canals to bring water. Some scholars disagree, thinking it might have been an unfinished building or used for mixing mortar. Soil analysis shows the field got water from both Chaco Wash and side canyons. Twenty-three similar fields have been found in Chaco Canyon.

Ancient corn cobs from Pueblo Bonito suggest that a lot of corn was brought into the canyon. It came from the Chuska Mountains (50 miles west) and the San Juan and Animas River areas (56 miles north). This corn might have fed workers during big building projects.

The black-on-white pottery found at Chaco Canyon came from different places. These included the Red Mesa Valley and the Chuska Valley. Most of the plain, everyday pottery was made locally. But more than half of the pottery found in the canyon was brought in from other areas.

After 1000 CE, almost no pottery was made in the canyon. It was made in other communities that had plenty of firewood for their kilns. From 1030 to 1100, much more pottery was imported. The large trade network suggests that skilled local artists supplied distant communities as well as their own.

What Was Chetro Ketl For?

Stephen Lekson believes Chetro Ketl was not just for many families to live in. He thinks the smaller round rooms were not kivas, but a fancy type of pit-house. He suggests Chacoan great houses were royal palaces. Chetro Ketl would have been a home for important people. It also would have been a center for government, storage, crafts, and rituals. Many scholars disagree, because they think palaces only exist in states, and they don't believe a Native American state existed north of Mexico. Lekson thinks this idea limits how complex Native American societies could be.

The rooms at Chetro Ketl often lack artifacts. This suggests they were used mainly for storing grain. But the amount of space seems too large just for food storage. So, this idea isn't widely accepted. Many of these rooms are plain inside and are under several stories. Their huge size might have been meant to impress people.

The rooms might have stored ritual objects. The great house might have been mainly for priests. It could also have housed pilgrims during community events. These pilgrims might have helped build Chetro Ketl. This would show their connection to the larger Chacoan group. The area between Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito might have been a central place for ceremonies. Since water was so important, Chacoan rituals probably focused on prayers for rain.

The Chacoan System

The Chacoan people had a way to send messages over long distances using smoke and mirrors. Messages could be sent between Pueblo Alto, Huérfano Mountain, and Chimney Rock Pueblo in minutes. An ancient road runs north from Chetro Ketl. It joins the Great North Road. This road network was used from 1050 to 1140. It helped people get to water, farms, and connect with other great houses. It also helped transport goods, timber, and people across the San Juan Basin.

In 1982, Robert Powers suggested that the road network showed a large, organized system of communities. He thought Chaco Canyon was the main center of this system. He believed great houses like Chetro Ketl helped manage things between the canyon and other communities. In 1993, David R. Wilcox suggested that a state-level society developed at Chaco. He thought Pueblo Bonito or Chetro Ketl was the main administrative center.

Stephen Lekson developed a theory called the Chaco Meridian. He noticed that important Ancestral Puebloan sites like Aztec Ruins, Chaco Canyon, and Paquime in Mexico are all on roughly the same line of longitude. He thinks this shows a special connection between them. The Great North Road also generally follows this line.

Most researchers agree that ritual was a strong part of Chacoan life. They see Chaco as a regional center with important ceremonies. Early estimates for the canyon's population were as high as ten thousand. But a figure closer to two thousand is more likely. Chaco was a ceremonial center and a "place of ritual architecture." Pilgrims from about 200 great house communities would visit. They brought many goods, like turquoise, shells, timber, and food.

Studies show that turquoise from Chetro Ketl came from mines near Santa Fe, New Mexico. More than half of the stone tools found at Chetro Ketl's trash mound came from the Chuska Mountains. The Chacoans received many imports, but there's little evidence of them sending goods out. This suggests they were consumers, not big producers or distributors.

Scholars still debate if Chacoan society was mainly political or mainly ritual-based. Evidence suggests that people in great houses like Chetro Ketl were of a higher social class. This might point to a society with different levels of power. Others see Chaco as an equal society, with its economy driven by its role as a ceremonial center. Since there hasn't been much modern digging, this question is still open.

Lekson believes that by the later period (1075 to 1140), Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Pueblo del Arroyo were like one big settlement. He thinks the area near South Gap was "nearly urban." At its peak, the Chacoan system covered a huge area, about the size of Portugal. The population of the region in the early 11th century was around 55,000 people.

Damage and Protection

After Chetro Ketl was rediscovered in the early 1800s, it started to fall apart much faster. Its wooden parts were especially vulnerable. Soldiers, cattlemen, and travelers took wood from the building. A balcony that was there in 1901 was gone by 1921 because people removed the beams for wood. Digging during archaeological work also made the wood decay faster.

The Chaco Wash, a stream that gets wider and deeper during summer rains, also threatens the ruins. The large trash mound has been almost destroyed by repeated digging and by streams changing course. Treasure hunting, livestock grazing, and early efforts by the National Park Service also damaged the structure. Deep excavations made the Chaco Wash more likely to flood. A flood in 1947 destroyed walls and caused part of the north wall to collapse.

In the late 1980s, a program was started to protect Chetro Ketl's original timbers. Parts of the site were reburied with soil. Special materials were added to keep the area dry. This program also developed ways to test ancient wood for decay. Experts note that Chetro Ketl is "deteriorating before our eyes." Its ability to provide detailed information is slowly disappearing.

Images for kids

-

The San Juan Basin, USGS map, 2002

-

Area occupied by the Ancestral Puebloans

See also

In Spanish: Chetro Ketl para niños

In Spanish: Chetro Ketl para niños

![Large square map of northwestern New Mexico and neighboring parts of, clockwise from left, western Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado. The map region has a green and blocky rectangular-crescent area at its center labeled Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Radiating from the green region are seven segmented gold lines: "[p]rehistoric roads", each several dozen kilometers in length when measured according to the map scale factor. Roughly seventy red dots mark the location of great house[s]; they are widely spread across the map, many of them far from the green area, near the extremes of the map, more than one hundred kilometers from the green area. Two proceed roughly south, one southwest, one northwest, one straight north, and the last to the southeast. Yellow dots mark the location of modern settlements: Shiprock, Cortez, Farmington, and Aztec to the northwest and north; Nageezi, Cuba, and Pueblo Pintado to the northeast and east; Grants, Crownpoint, and Gallup to the south and southwest. They are connected by a network of gray lines marking various interstate and state highways. A fan of thin blue lines along the northern margins of the map depict the San Juan River and its communicants.](/images/thumb/6/6a/Prehistoric-Roads.jpg/300px-Prehistoric-Roads.jpg)