Chief White Eagle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

White Eagle

|

|

|---|---|

| Qithaska | |

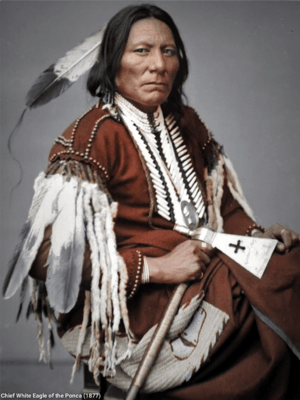

Chief White Eagle in 1877

|

|

| Hereditary chief sovereign of the Ponca | |

| In office 1870–1904 |

|

| Preceded by | Iron Whip (1846-1870) |

| Succeeded by | Horse Chief Eagle (1904-1940) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1825 Niobrara River valley, Northern Great Plains |

| Died | February 4, 1914 (aged 88–89) White Eagle, Oklahoma |

| Resting place | Monument Hill Marland, Oklahoma 36°34′10″N 97°08′41″W / 36.56944°N 97.14472°W |

| Citizenship | Ponca |

| Nationality | Ponca |

| Relations |

|

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

Chief White Eagle (born around 1825 – died February 3, 1914) was an important Native American leader. He served as the main chief of the Ponca people from 1870 to 1904. During his 34 years as chief, the Ponca faced huge changes and challenges. This included the forced removal of his people in 1877, known as the Ponca Trail of Tears. White Eagle bravely fought for justice for his people. He used the American media to speak out against the United States government and its policies. His efforts helped change how the government treated Native Americans. He became a key figure in the early Native American civil rights movement.

Contents

Early Life and Family History

White Eagle was born in the Niobrara River valley, near where the Niobrara and Missouri Rivers meet. This area is now the border between South Dakota and Nebraska.

At the time of his birth, the Ponca people were led by a main chief. This chief inherited his position and was advised by thirteen other chiefs. The main chief was the leader of the Ponca nation. White Eagle's family had held this leadership role for a long time. His grandfather, Chief Little Bear, became chief in the late 1700s.

White Eagle shared the story of how his grandfather, Little Bear, became chief. Little Bear was a brave young man from a poor family. He was asked by the old chief, Little Chief, to avenge his son's death. Little Bear accepted the challenge. He went on four successful expeditions and always shared his spoils with Little Chief. Because of Little Bear's bravery and success, Little Chief kept his promise and stepped down, making Little Bear the new chief.

White Eagle's exact birth year is not known for sure. Some reports say he was born as early as 1803 or as late as 1840. However, records show he was a junior chief in 1846. He was part of a group that met with Brigham Young and the Mormon pioneers. The Mormons recorded the death of White Eagle's grandfather, Little Bear, in 1846. They also saw power pass to White Eagle's uncle, Two Bulls, and then to his father, Iron Whip. White Eagle became chief after his father in 1870. This matches the story White Eagle told about his family's leadership.

White Eagle as Chief (1870-1904)

The Ponca Trail of Tears (1870-1877)

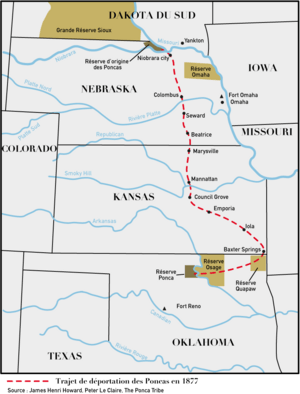

White Eagle's time as chief was largely defined by the forced removal of the Ponca people. In 1877, the U.S. government unlawfully moved the Ponca from their lands in the Dakota Territory. This was against the Ponca Treaty of 1865 and American law. This forced journey was called the Ponca Trail of Tears. It was a 600-mile march through three states, and many people died along the way.

The removal happened in two groups. The first group of about 170 Ponca left on April 16, 1877. The second, larger group of about 500 people included White Eagle and his vice chief, Standing Bear. For almost a month, White Eagle and Standing Bear tried to stop the federal agent, Edward Cleveland Kemble, from forcing the Ponca to move.

On April 24, 1877, General William Tecumseh Sherman sent soldiers to force the Ponca to leave. White Eagle spoke to the soldiers, asking why they were armed against his peaceful people. He reminded them that the Ponca would rather die on their land than be forced to leave.

On May 16, 1877, White Eagle told his people, "We, your chiefs, have worked hard to save you from this. We have resisted until we are worn out." He left the decision to them. After a long silence, the Ponca decided they had no choice but to move. White Eagle later recalled that soldiers gathered their women and children, broke into their homes, and took their belongings. They locked up farming tools and other heavy items, which the Ponca never saw again.

The removal was a terrible 54-day journey, from May 16 to July 9, 1877. Many people died. Heavy rains made the dirt roads muddy. A tornado hit the group on June 7, 1877, killing one child and hurting many others. More children and elderly people died in the following days.

On July 2, a frustrated Ponca named Buffalo Chip tried to attack White Eagle, blaming him for the deaths. The federal agent described the scene as chaotic, with loud crying from women and children. A week later, the Ponca finally reached the Quapaw Agency in the Indian Territory. The agent noted the extreme heat, exhausted teams, and tired people.

The Ponca lost their homes, personal items, and farm tools. They were moved to a swampy area in the Indian Territory, a tropical climate they were not used to. No preparations had been made for them. Within six months, 141 more Ponca died from diseases like malaria and yellow fever. This meant about 30% of the Ponca population died. White Eagle lost his wife, four of his children, and his father, Iron Whip, during this time.

Fighting for Native American Rights (1877-1881)

After the removal, White Eagle led a group of Ponca leaders to Washington, D.C. They went to speak with President Hayes and Congress about the illegal removal. They arrived on November 8, 1877.

White Eagle's leadership was key in a major civil rights case in 1879, Standing Bear v. Crook. This ruling recognized Native Americans as people with civil rights under the U.S. Constitution for the first time. White Eagle and Standing Bear worked hard to get their ancestral land back. They also wanted compensation for the government breaking the 1865 Ponca Treaty and mishandling the removal.

Many famous Americans supported the Ponca, including poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and author Helen Hunt Jackson. Jackson wrote an important book called "A Century of Dishonor" about the injustices faced by Native Americans. A Nebraska journalist, Thomas Tibbles, traveled the country to raise money for the Ponca to take their case to the Supreme Court. He believed that if people knew the truth, they would help White Eagle.

Unlike earlier forced removals, the Ponca removal was widely seen as illegal. It went against the 1865 treaty and a 1876 law that said the government needed White Eagle's consent to move the Ponca. White Eagle had refused to give consent. As public anger grew, the Senate investigated the removal. They found that the U.S. government had done a great injustice to the Ponca.

In January 1881, White Eagle negotiated a settlement with the U.S. government. The Ponca agreed to stay in the Indian Territory in exchange for $125,000 (which would be about $3.6 million today). This decision surprised many. However, White Eagle chose this because it offered safety from Sioux attacks and new economic chances, like leasing land. On October 22, 1880, White Eagle showed his intention to stay by laying the cornerstone of a new school on the Ponca Agency. He did this with Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce.

The U.S. government changed its policies toward Native Americans after the Senate investigation. The forced removal policy, which started under President Jackson, was ended. White Eagle was later given credit for making this change happen. He said, "We have been robbed of all we owned, but if we had thousands we would spend it all in bearing the expenses of the lawsuit carried on for us. We have nothing but our thanks to give."

Against the Dawes Act and Oklahoma Land Run

After getting reparations, White Eagle continued to fight for Native American rights. He was one of the few leaders who spoke out against the Dawes Act of 1887. This act tried to make Native Americans live like white Americans. It offered citizenship to individual Native Americans if they gave up their tribal governments and communal lands.

White Eagle warned that the Dawes Act would "pluck the Indian like a bird." He meant it would strip Native Americans of their culture and land. He fought to keep his power as chief, saying that "a chieftainship is hard to break up." He strongly disagreed with the part of the act that allowed the government to take "surplus" land. He said, "when animals come out, there is grass for them to eat, and we would like to have land for the children when they come."

White Eagle's prediction about the Dawes Act came true. Senator Henry L. Dawes, who the act was named after, later called White Eagle "the clearest head of all" Native American leaders on the issue. Carl Schurz, President Hayes' Secretary of the Interior, called White Eagle "one of the greatest men among the Indians."

By 1889, White Eagle's efforts to stop American settlers from taking land had failed. The Ponca faced life on a reservation. The government wanted them to give up their traditions.

After the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889, President Benjamin Harrison formed a group to get land from thirteen Native American nations, including the Ponca. The goal was to open this land to American settlers. In 1891, White Eagle told President Harrison's group that new immigrants should "stay on their own reservations."

By 1892, Harrison's group had taken land from every nation except the Ponca. On March 17, 1892, White Eagle led the Ponca in refusing to negotiate. The commissioners tried to show the Ponca what 80 acres looked like, but White Eagle said he already knew. The commissioners threatened that the Ponca would have no peace until they sold their land.

On April 12, 1892, President Harrison's offer was made: each Ponca would get 80 acres and $20. The government would pay $69,000 for the extra land, and the rest of the money would earn interest. White Eagle was very critical of this offer. The Ponca strongly resisted, and the commission could not get them to agree.

A young Ponca said that since moving to the Indian Territory, the chiefs were not the only ones to decide things. He said the land belonged to all the men, women, and children, and they had a right to say what should be done with it. White Eagle continued to use his authority and delay tactics, saying he needed more time to understand the federal plan.

Leasing Ponca Land to the 101 Ranch and Marland Oil

Even though he opposed the Dawes Act, White Eagle found ways to use it to benefit his people. When a large oilfield was found under the Ponca reserve in 1911, he worked with oil tycoon E.W. Marland. He also leased a lot of Ponca land to the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch. This ranch became famous for its Wild West shows, which gave jobs to the Ponca people. These shows entertained important people like King George V and Theodore Roosevelt.

In September 1883, White Eagle joined young Joe Miller and other Ponca leaders at the Alabama State Fair. They set up a traditional Indian village and performed dances. White Eagle also performed in the 101 Ranch Wild West Show in Birmingham, Alabama, in late 1902. At that time, White Eagle needed permission from the government to leave the Ponca Reservation.

Later Life and Death (1904-1914)

Stepping Down as Chief (1904)

White Eagle officially stepped down as chief on May 8, 1904. His son, Horse Chief Eagle, took his place. Horse Chief Eagle would later be known as the last hereditary chief in the United States. This was because of the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936, which stopped non-democratic Native American governments. White Eagle's ceremony and a traditional buffalo hunt that followed were attended by about 13,000 people. The newspapers called it the last buffalo hunt in the history of the Great Plains.

Death (1914)

White Eagle died on February 3, 1914. He is buried on Monument Hill in Noble County, Oklahoma.

Honors

Nieuw Amsterdam by Salvador Dalí

In 1899, American artist Charles Schreyvogel made a bronze statue of White Eagle's head. In 1974, the famous Spanish artist Salvador Dalí changed this statue using his unique artistic method. Dalí turned White Eagle's eyes into a scene showing 17th-century Dutch colonists celebrating the purchase of Manhattan Island. He also changed White Eagle's chin into a tabletop and his lips into a fruit basket.

This artwork, called Nieuw Amsterdam, is shown at the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. The museum says White Eagle was a "celebrated chief" known for speaking out against confining his people to reservations. They also note his role in getting equal rights for Native Americans in the 1870s.

Other Honors

- The White Eagle Oil & Refining Co. was started in 1911. By 1930, it had gas stations in 11 states.

- The town of White Eagle, Oklahoma is named after him. It is the main office for the Ponca Nation of Oklahoma today.

- White Eagle appears on the Ponca Code Talkers Medal, made by the United States Mint in 2013.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jefe Águila Blanca para niños

In Spanish: Jefe Águila Blanca para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |