Columbia Island (Washington, D.C.) facts for kids

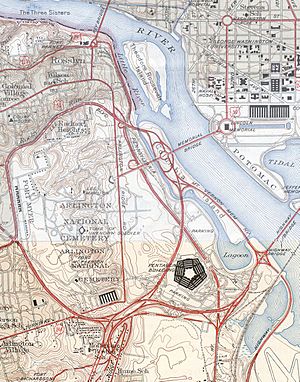

Aerial view of Lady Bird Johnson Park (outlined in red)

|

|

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Potomac River, Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°52′56″N 77°03′26″W / 38.8823342°N 77.0571996°W |

| Total islands | 1 |

| Area | 0.19 sq mi (0.49 km2) |

| Length | 1.32 mi (2.12 km) |

| Coastline | 2.95 mi (4.75 km) |

| Highest elevation | 22 ft (6.7 m) |

| Administration | |

|

United States

|

|

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

Lady Bird Johnson Park, once called Columbia Island until 1968, is an island in the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., USA. It started forming naturally in the late 1800s as part of Analostan Island. Over time, water and floods separated it.

The U.S. government later added material dug from the Potomac River to the island between 1911 and 1922, and again from 1925 to 1927. The island was also shaped to be the western end of the Arlington Memorial Bridge. This bridge acts as a grand entrance to the nation's capital.

Inside the park, you'll find the Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove, the Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial, and the Columbia Island Marina. The National Park Service manages the island, park, memorials, and marina as part of the George Washington Memorial Parkway.

Contents

How Columbia Island Was Formed

Columbia Island is a mix of natural land and land created by people. In 1818, it didn't exist. Back then, Analostan Island (now Theodore Roosevelt Island) was mostly rock and very close to the D.C. shoreline.

Because forests were cut down and more farming happened upstream, the river's northern bank wore away. This made the gap between Analostan Island and the shore wider. At the same time, a lot of silt (fine dirt) built up around Analostan Island.

By 1838, Analostan had almost doubled in length towards the south. By 1884, this new southern part was well-formed and had a thriving wetland. However, the river slowly eroded the middle of Analostan Island, cutting off Columbia Island from its original land.

Between 1911 and 1922, the Potomac River was dug out many times. This was done to make the river deeper and to widen the space between Analostan/Theodore Roosevelt Island and Columbia Island. This helped prevent flooding in the "Virginia Channel" west of Analostan/Roosevelt Island.

The material dug from the river was piled high on Columbia Island. This helped make the island taller, longer, and wider, giving it its current shape. The island was completely filled in by the spring of 1924.

The new island got its name around 1918 from an engineer working for the District of Columbia. The name "Columbia Island" first appeared in The Washington Post in April 1922. In the same year, the island was given to the National Park Service to manage.

Developing Columbia Island for the Arlington Memorial Bridge

Building the Arlington Memorial Bridge and Expanding the Island

In 1922, Congress allowed a design contest for the new Arlington Memorial Bridge. The winning design came from the firm McKim, Mead and White, with William Mitchell Kendall as the main architect. Congress approved building Kendall's bridge on February 24, 1925.

The law also included building roads and walkways at both ends of the bridge. It also planned for B Street NW to become a new ceremonial road. A road called Memorial Drive was also planned to connect the bridge to Arlington National Cemetery.

Early plans for the bridge showed it ending on Columbia Island. This meant Columbia Island needed to be made larger. The United States Army Corps of Engineers was already planning to dig out the Potomac River and make Columbia Island bigger.

So, on April 1, 1925, Secretary of War John W. Weeks ordered $114,500 to be spent on digging the river. The material dug out was to be put on Columbia Island. To make sure the island could support the bridge, the Corps also planned to build a 20-foot (6-meter) high wall around it.

The Corps and the bridge commission agreed to share the cost of this work in April 1925. This involved removing 2.5 million cubic feet (70,792 cubic meters) of river bottom. They also built 2,000 feet (610 meters) of seawall and 15,000 feet (4,572 meters) of levee. About 40 acres (16 hectares) of Columbia Island were removed to widen the main river channel. The island's height was raised from 6 feet (1.8 meters) to 22 feet (6.7 meters) above water over two years.

Early Ideas for Columbia Island's Design

Several groups had to approve the bridge and island plans. These included the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) and the National Capital Parks Commission (NCPC).

In January 1926, the CFA and NCPC discussed how the Virginia end of the bridge would serve as a gateway to Washington. They agreed on a plan for roads spreading out from the bridge. However, in December 1926, the CFA learned that Arlington National Cemetery might expand. This changed the bridge's approaches, so the CFA asked Kendall to rethink his design for Columbia Island.

Kendall presented a new design in May 1927. His plan included traffic circles on Columbia Island. By June 30, 1927, the river dredging was almost done. Columbia Island was reshaped and finished. The 200-acre (81-hectare) island now rose 22 feet (6.7 meters) above the water. The next month, work began on plans for the Boundary Channel Bridge. This bridge would connect Arlington Memorial Bridge to Memorial Drive, crossing the Boundary Channel that separates Columbia Island from Virginia.

Kendall's May 1927 design for Columbia Island was debated for two years. An architect named Milton Bennett Medary suggested that Columbia Island should have a simple, formal look. This would help it connect the grand Neoclassical bridge to the more natural landscape of Arlington National Cemetery. The CFA agreed with Medary.

In May 1929, the CFA approved pylon designs for Columbia Island. But the main plaza and roads on the island needed more study.

Building the Boundary Channel Bridge

Work on the Boundary Channel Bridge began in spring 1929. They immediately found problems with unstable rock and sand under the bridge's foundations. These issues had to be fixed before construction could continue. By June 30, 1929, the western end of the Arlington Memorial Bridge was almost done. Many concrete columns for the Boundary Channel Bridge were also finished.

By June 1930, some extra filling of Columbia Island was all that was needed to finish the Arlington Memorial Bridge. But the main plaza and monuments on Columbia Island were not yet built because the CFA hadn't approved a final design.

Also, work on the western half of the Boundary Channel Bridge had stopped. Tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad ran along the Virginia shoreline. To avoid a crossing at the same level as Memorial Drive, the CFA suggested lowering these tracks by 20 feet (6.1 meters). This meant extending the Boundary Channel Bridge, requiring new engineering studies.

By June 1930, an agreement was reached to move the train tracks closer to the river. A tunnel under the bridge would be built for the tracks first. This would allow trains to keep running without interruption. The Pennsylvania Railroad also agreed to give the old track land to the government once the new tracks and tunnel were ready.

Changes to the Great Plaza Plan

In July 1930, the CFA looked at designs for the Columbia Island plaza again. Repairs were also made to the island's walls. In September, the CFA reviewed designs for memorial columns and landscaping but didn't approve them. Members started to wonder if the columns truly honored the reunited North and South.

The Great Depression was also making it hard to get money for the bridge project. To save money, the CFA removed plans for Greek Revival temples and many statues on Columbia Island. Instead of building long roads, only short sections next to the main plaza would be built. Removing the statues saved $478,000.

More material was added to Columbia Island in October and November 1930 to make it higher. The new goal was to raise the island to 30 feet (9.1 meters) above the average water level.

The road across Columbia Island, connecting Arlington Memorial Bridge with Boundary Channel Bridge, was finished in December 1930.

The CFA continued to work on the Columbia Island plaza design in 1931. They discussed the columns again in January and removed a granite fence around the plaza, saving $400,000. But by September, they still hadn't decided on a new plaza design.

Removing the Memorial Columns

The design problems for Columbia Island's great plaza were finally solved in late 1931 by President Herbert Hoover. Two airfields, Hoover Field and Washington Airport, were located just south of Columbia Island in Virginia. In spring 1931, an officer named Ulysses S. Grant III warned that the huge memorial columns planned for Columbia Island would be a danger to airplanes. But no one listened.

On September 28, 1931, the United States Department of Commerce told the CFA that the tall columns were a risk to aviation. They said the columns would interfere with air traffic and demanded they be removed or brightly lit. The Washington Board of Trade also opposed the columns.

Grant agreed that if the columns were a hazard, they should be removed. The CFA agreed to put street lights on the roads to warn pilots. However, they strongly opposed floodlighting the memorial columns, as it would compete with the softer lighting of the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington House. William Kendall, the architect, was so determined to keep the columns that he wrote to President Hoover. He told Hoover to move the airport if it interfered with his design.

On October 12, Hoover ordered a review of the columns. The Washington Post reported that many officials were also worried about the high cost of the columns. They were estimated to cost at least $500,000, plus another $100,000 for their foundations.

Senator Hiram Bingham III, who loved aviation, started gathering aviation groups to oppose the columns. He even threatened to pass a law to ban aviation hazards in D.C. On November 27, 40 pilots wrote to President Hoover demanding the columns be removed. Three days later, the Board of Trade also contacted Hoover directly to argue against the columns.

Facing strong opposition, the bridge commission voted to remove the columns in December 1931. They asked Kendall for yet another new design for Columbia Island. People suggested other ideas like fountains or towers that could retract for planes, but no decision was made.

Finishing Columbia Island

By April 1932, work was well underway to move the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks. The new route was prepared, tracks were laid, and the western end of Boundary Channel Bridge was designed. The formal opening of Memorial Avenue and the Boundary Channel Bridge happened on April 9.

However, the worsening economy almost stopped all development on Columbia Island. On April 7, 1932, the House of Representatives removed all $840,000 planned for the project for the next year. Design work on the great plaza stopped immediately. So did the final filling of the island, landscaping, and road grading.

Franklin D. Roosevelt became President in March 1933. He believed that spending a lot of money on public projects would help the economy and reduce unemployment. He proposed the National Industrial Recovery Act, which included $6 billion for public works. The act passed on June 13, 1933, and Roosevelt signed it into law on June 16. The Public Works Administration (PWA) was quickly set up to give out these funds.

On July 13, just a month after the PWA was formed, the agency announced a $3 million grant to finish work on Columbia Island and other parts of the Arlington Memorial Bridge project. In November, the CFA and NCPC met to decide how to proceed.

On December 4, the agencies announced that PWA money would be used to build bridges on the north and south ends of the island. These bridges would connect to Lee Highway and a new highway being planned in the south. The southern bridge became known as the Humpback Bridge because it had a slight rise in the middle.

To connect to these bridges, the roads on Columbia Island also needed to be finished. These roads were planned in January 1934. The CFA and NCPC also discussed adding a new, large traffic circle to the center of the island to avoid traffic jams. The design for the northern bridge was approved in October 1936.

The CFA continued to discuss the Columbia Island great plaza in January 1935 but couldn't make a decision. Without more money, only bridge construction and small improvements could be made. Improved landscaping designs for the Boundary Channel Bridge were approved in March 1936. Seven months later, the CFA began studying the lighting for the Arlington Memorial Bridge, Columbia Island, and Memorial Drive.

Smaller parts of Columbia Island were finished in the late 1930s. A second northern bridge, meant to connect with Lee Boulevard (now Arlington Boulevard), was approved in 1937. This new bridge and the bridge over the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks were completed in July. Although the CFA kept discussing plans for the great plaza as late as January 1938, no major improvements were made. Memorial Avenue was completed in September 1938.

The final parts of Columbia Island were built in 1939 and 1940. In April 1939, Congress approved $100,000 to build the last connections between the bridges and the central traffic circle on the island. This money also paid for sidewalks, trails, parking lots, and landscaping. The CFA finally approved the lamppost design for the island in January 1940. The last big improvement came in September 1940, when a "racetrack" feature was built. This was a larger outer traffic circle to handle the increasing north-south traffic. It helped drivers avoid the bottleneck at the central traffic circle.

Columbia Island's Later History Before Renaming

After filling operations stopped in 1932, Columbia Island naturally settled. By 1941, this settling had damaged the ends of the Boundary Channel Bridge. The Bureau of Public Roads placed steel supports under each end to strengthen them.

Bridge work on Columbia Island continued in the 1940s. In January 1942, the United States Department of Defense realized that the rapid growth of the Pentagon workforce due to World War II would strain local roads. A new main road, Army-Navy Boulevard (now Army-Navy Drive), was being built. It would connect Pentagon City to the Pentagon, then continue to Columbia Island, run up the center, and connect with the Arlington Memorial Bridge. A bridge carrying Army-Navy Boulevard over the Boundary Channel was approved in January 1942. In 1948, the northwestern bridge connecting Columbia Island to Lee Boulevard (now Arlington Boulevard) was rebuilt.

Another bridge linking Columbia Island and Virginia was suggested in 1958. At that time, one possible route for the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge was south of Little Island. District of Columbia officials asked to build a small approach bridge over Boundary Channel, but the CFA refused. By June 1958, the bridge's location moved north, making a bridge over Boundary Channel unnecessary.

In 1958, the northwestern bridge connecting Columbia Island to Arlington Boulevard was widened from four to six lanes. The northern bridge carrying the George Washington Memorial Parkway over Boundary Channel was changed in late 1962. This was part of a larger road change to link Arlington Boulevard to the new Theodore Roosevelt Bridge. A traffic light, the only one on the parkway, was installed to control traffic during this change. The new bridge was finished and the light removed in September 1964.

A year later, in September 1965, a new bridge opened just west of the South Washington Boulevard bridge. The George Washington Memorial Parkway was expanding north, which meant moving the parkway's southbound lanes onto the Virginia shoreline and off the northern part of Columbia Island. The new bridge connected the new parkway alignment with the old one.

Veterans of the United States Navy and the United States Merchant Marine had long felt there was no memorial in Washington, D.C., honoring their service. Congress fixed this in the 1920s, and a memorial was designed by 1922. However, raising money for it took much longer than expected.

Ground for the memorial on Columbia Island was broken on December 2, 1930, by several important officials. Work on the memorial then stopped for almost three years. The statue itself was finally put in place in 1934. However, due to lack of money, the statue stood on a concrete base instead of a wavy green granite one.

In May 1934, the group overseeing the memorial asked for a $100,000 grant to finish the granite steps, but no money came. Finally, funding for the memorial's completion began moving through Congress. With congressional support, the Works Progress Administration gave $39,000 to finish the memorial in 1939. This included adding the wavy green granite steps, creating a concrete plaza around the memorial, installing two flagstone walks leading to it, and landscaping the area.

Lady Bird Johnson Park Today

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the National Park Service greatly improved the landscaping of Columbia Island. This was part of a nationwide effort to beautify cities, supported by then–First Lady Lady Bird Johnson between 1964 and 1968.

More than one million daffodils and 2,700 dogwood trees were planted in the park between 1965 and 1968. These plants were paid for by the National Park Service, the Society for a More Beautiful National Capital, and the 1965 Presidential Inaugural Committee. Columbia Island was renamed Lady Bird Johnson Park by the United States Department of the Interior on November 12, 1968, to honor her work.

After the Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove was dedicated in Lady Bird Johnson Park in 1976, the National Park Service built a 300-foot (91-meter) footbridge over the Boundary Channel in 1977. This connected a new 30-car parking lot near the Pentagon to the park and memorial. The bridge and parking lot cost $500,000.

In spring 1987, the National Park Service repaved the South Washington Boulevard bridge to Lady Bird Johnson Park. They also started planning to rebuild the bridge by 1991.

Reconstruction of the Humpback Bridge began in January 2008. The bridge had not been updated since it was built and was carrying 75,000 vehicles a day, much more than it was designed for. Improvements included widening the bridge, adding barriers to separate sidewalks from traffic, and building an underpass. This underpass allows walkers and cyclists to go under the parkway instead of crossing it. The reconstruction also removed the famous "hump" in the middle of the bridge. However, the original stone facing was kept to preserve the bridge's historic look. The bridge reconstruction was finished in 2011, and the bike/pedestrian underpass opened in November. The underpass connected the Columbia Island Marina and the LBJ Memorial Grove with the Mt. Vernon Trail.

A children's garden was built on Lady Bird Johnson Park in spring 2008.

Lyndon Baines Johnson Memorial Grove

After President Johnson passed away in 1973, Brooke Astor and Laurence Vanderbilt started planning a memorial grove in his honor. Johnson loved this park when he was president. Congress approved the national memorial on December 28, 1973.

A grove with a large stone monument made of Texas granite was installed in 1975. Walking trails were also added, along with hundreds of white pine and dogwood trees among the grassy fields. The memorial was officially dedicated on April 6, 1976.

About the Island

The Boundary Channel of the Potomac River separates Lady Bird Johnson Park from the Virginia shoreline. The main part of the Potomac River surrounds the island on its other three sides. As of 2007, the island had 121 acres (49 hectares) of beautiful parkland.

Inside the park, you can find the Lyndon B. Johnson Memorial Grove, the Navy–Merchant Marine Memorial, and the Columbia Island Marina.

Lady Bird Johnson Park is easy to reach from downtown Washington via the Arlington Memorial Bridge. You can also get there from Arlington National Cemetery using Memorial Drive, and from Northern Virginia via the George Washington Memorial Parkway. The Mount Vernon Trail runs along the side of the island facing the rest of D.C. It leads to Theodore Roosevelt Island in one direction and Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in the other. The Pentagon can be seen from the western side of the island near the marina at the southern tip.

See also

In Spanish: Isla Columbia (Distrito de Columbia) para niños

In Spanish: Isla Columbia (Distrito de Columbia) para niños