Combat of the Thirty facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Combat of the Thirty |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Breton War of Succession | |||||||

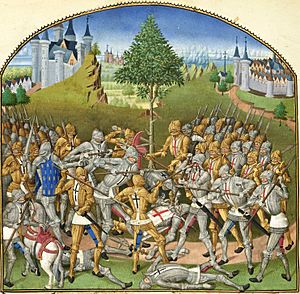

Penguilly l'Haridon: Le Combat des Trente |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

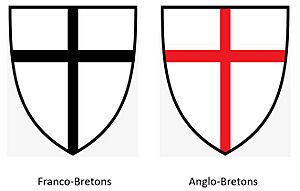

| House of Blois, Brittany Kingdom of France |

House of Montfort, Brittany Kingdom of England |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Jean de Beaumanoir | Robert Bemborough † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30 knights and squires | 30 knights and squires | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2 dead | 9 dead | ||||||

The Combat of the Thirty (also known as Combat des Trente in French) was a famous arranged fight that happened on March 26, 1351. It was a key event in the Breton War of Succession, a big conflict to decide who would rule the Duchy of Brittany. This special battle took place between two groups of 30 chosen fighters, including knights and squires, from each side.

The fight happened in Brittany, at a spot halfway between the castles of Josselin and Ploërmel. The challenge was made by Jean de Beaumanoir, a captain who supported Charles of Blois (backed by the King of France). He challenged Robert Bemborough, a captain who supported Jean de Montfort (backed by the King of England).

After a very tough battle, the French-Breton side, supporting the House of Blois, won. This combat was later celebrated by writers and poets as a great example of chivalry, which was the code of honor for knights. One famous writer, Jean Froissart, said the warriors fought "as valiantly on both sides as if they had been all Rolands and Olivers," referring to legendary heroes.

Contents

Why the Combat Happened

The Breton War of Succession was a fight between two powerful families, the House of Montfort and the House of Blois. Both wanted to control the Duchy of Brittany. This local war became part of the much larger Hundred Years' War between France and England. England supported the Montfort family, and France supported the Blois family. By 1351, the war in Brittany was stuck, with each side holding different castles and towns.

Robert Bemborough, an English knight leading the Montfort side in Ploërmel, was challenged to a single combat (a one-on-one duel) by Jean de Beaumanoir, the French-Breton captain of nearby Josselin. According to the writer Froissart, Bemborough suggested making it a bigger fight between twenty or thirty knights from each side. Beaumanoir eagerly agreed to this idea.

The exact reason for this tournament isn't fully clear. Some early writings say it was a purely chivalric event. This means it was fought to honor the ladies involved in the war, Joan, Duchess of Brittany (Blois side) and Joanna of Flanders (Montfort side). These women were leading their groups because Joan's husband was captured, and Joanna's husband had died. Writers like Jean le Bel and Jean Froissart described it as a matter of honor, with no bad feelings between the fighters.

However, popular songs and poems told a different story. They said that Bemborough and his knights were cruel to the local people. The people then asked Beaumanoir for help. In these stories, Beaumanoir was a hero protecting the helpless. He was shown as a good Christian, while Bemborough was shown relying on magic. This version became popular later, suggesting Bemborough's cruelty was to get revenge for another knight's death.

No matter the reason, the fight was set up like a tournament. It took place at a spot called the chêne de Mi-Voie (the Halfway Oak) between Ploërmel and Josselin. There were refreshments and many spectators watching. Bemborough is said to have hoped people would talk about this fight "throughout the world" for a long time.

Beaumanoir led thirty Bretons. Bemborough led a mixed group of twenty Englishmen, six German soldiers, and four Breton supporters of Montfort. It's not completely clear if Bemborough himself was English or German. His name is spelled in different ways, and some historians doubt he was German, even though early writers said so.

The Battle Itself

The battle was fought with swords, daggers, spears, and axes. Fighters were either on horseback or on foot. It was a very fierce and desperate fight. A famous moment happened when Geoffroy du Bois told his wounded leader, Beaumanoir, who was asking for water: "Drink thy blood, Beaumanoir; thy thirst will pass."

According to Froissart, both sides fought with great bravery. After several hours, four French-Breton fighters and two English-Breton fighters had died. Both groups were tired, so they agreed to a break to rest and treat their injuries.

When the battle started again, the English leader Bemborough was wounded and then killed, possibly by du Bois. After this, the English side formed a tight defensive group. The French-Bretons attacked them repeatedly. A German soldier named Croquart was said to have fought very bravely, helping the English-Breton defense.

In the end, the victory was decided by Guillaume de Montauban, a squire. He got on his horse and charged into the English line, breaking it apart. He knocked down seven of the English fighters, and the rest were forced to give up. Many fighters on both sides were either dead or badly hurt. Nine English-Breton fighters were killed.

How it was Remembered

Even though the Combat of the Thirty didn't change the final outcome of the Breton War, people at the time saw it as a perfect example of chivalry. Poets sang about it, and it was written about in famous books like the chronicles of Froissart. It was greatly admired in poems and art. A special stone was placed where the combat happened, and the French king Charles V of France even ordered a tapestry (a woven picture) to show the battle. The fighters became so famous that twenty years later, Jean Froissart saw a survivor, Yves Charruel, being honored at King Charles V's table.

Historians say that this chivalric view focused on how the fight was done, not just who won. Both sides were seen as equally brave for agreeing to rules, fighting their best, and not running away.

Later, the combat was seen differently, especially because of popular songs about it. In these songs, the English knights were shown as villains, and the French-Breton fighters were loyal local heroes. The songs listed each fighter and presented the French-Breton side as local nobles protecting their people. The Montfort side was shown as foreign soldiers and criminals who "torment the poor people."

After Brittany became part of France, this version of the story was used in French national history. It was shown as a heroic fight against foreign invaders. Since France had lost the larger War of Succession, the Combat of the Thirty was promoted as a symbolic victory. In 1819, a large monument was built at the battle site by King Louis XVIII. It said that the "thirty Bretons" fought to defend the poor and workers, and they defeated foreigners.

For the English, the combat was less important. However, the fact that the French-Bretons won because one fighter got on his horse to break the English line was later seen by some as cheating. The writer Arthur Conan Doyle even wrote a historical novel, Sir Nigel, where the English leader accepts the challenge fairly, but the French-Bretons win only because a squire rides his horse into the English, even though the fight was supposed to be on foot.

Combatants

Here are the names of the knights and squires who fought in the Combat of the Thirty:

|

Franco-Breton force

Squires

|

Anglo-Breton force

Squires and men-at-arms

|

† indicates that the combatant was killed. The English side lost nine killed in total and the remainder captured. The Franco-Breton side lost at least three and probably more. A number of them were captured, taken to Josselin and executed.

See also

- Battle of the North Inch, a similar battle in Scotland from 1396

Literature

- A Distant Mirror by Barbara W. Tuchman (1978)

- Le Poème du combat des Trente, in the Panthéon litteraire;

- H.R. Brush, ed., "La Bataille de trente Anglois et de trente Bretons," Modern Philology, 9 (1911–12): 511–44; 10 (1912–13): 82–136.

- "The combat of the thirty. From an old Breton lay of the fourteenth century". Translated by English novelist William Harrison Ainsworth. In: Browne, H. Knight; Cruikshank, G.; Smith, A.; Ainsworth, W. Harrison; Dickens, C. (18371868) (1859). Bentley's Miscellany Volume XLV. London: Richard Bentley. pp. 5–10, 445–459.

- Steven Muhlberger (tr. and ed.), The Combat of the Thirty, Deeds of Arms Series, vol. 2 (Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2012).

- Steven Muhlberger, Deeds of Arms: Formal combats in the late fourteenth century, (Highland Village, TX: The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2005), 76–120.

- Sébastien Nadot, Rompez les lances ! Chevaliers et tournois au Moyen Age, Paris, ed. Autrement, 2010. (Couch your lances ! Knights and tournaments in the Middle Ages...)

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sir Nigel.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |