Coquille River (Oregon) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Coquille River |

|

|---|---|

Aerial view of the Coquille near its mouth

|

|

|

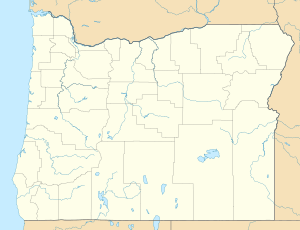

Location of the mouth of the Coquille River in Oregon

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Coos |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Southern Oregon Coast Range Myrtle Point 17 ft (5.2 m) 43°04′49″N 124°08′28″W / 43.08028°N 124.14111°W |

| River mouth | Pacific Ocean Bandon, Oregon 0 ft (0 m) 43°07′25″N 124°25′48″W / 43.12361°N 124.43000°W |

| Length | 36.3 mi (58.4 km) |

| Depth |

|

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 1,059 sq mi (2,740 km2) |

The Coquille River is a river in southwestern Oregon, United States. It is about 36 miles (58 km) long. The river flows through a mountainous area of about 1,059 square miles (2,743 km2) in the Southern Oregon Coast Range. It eventually empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Coquille River's water basin is located between the Coos River to the north and the Rogue River to the south.

Contents

Where Does the Coquille River Flow?

The Coquille River starts at Myrtle Point. This is where its two main parts, called forks, come together.

The North and East Forks

The North Fork Coquille River is about 53 miles (85 km) long. It begins in the northern part of Coos County and flows southwest. The East Fork Coquille River is about 34 miles (55 km) long. It starts in eastern Coos County and flows west to meet the North Fork.

The South and Middle Forks

The South Fork Coquille River is the longest part, at about 63 miles (101 km). It starts in southern Coos County, near the Wild Rogue Wilderness Area. It flows north and meets the Middle Fork Coquille River, which is about 40 miles (64 km) long. The South Fork then joins the North Fork at Myrtle Point.

Journey to the Pacific Ocean

After the forks join, the main river flows generally west. It passes by the town of Coquille. Finally, it reaches the Pacific Ocean at Bandon. This spot is about 20 miles (32 km) north of Cape Blanco. Just before it enters the ocean, the river is crossed by US Route 101. This crossing happens over a small drawbridge called Bullards Bridge.

What Are the Coquille River's Tributaries?

Many smaller streams and creeks flow into the Coquille River. These are called tributaries. Starting from where the river begins and moving towards the ocean, some of these named tributaries include:

- The North Fork and South Fork (which form the main river)

- Grady, Hall, Gray, Fishtrap, Glen Aiken, Pulaski, Rink, Fat Elk, Calloway, and China creeks

- Beaver, Iowa, and Hatchet sloughs

- Alder, Lampa, Lowe, and Bear creeks

- Offield Creek (which enters through Randolph Slough)

- Sevenmile and Fahys creeks

- Peterson Gulch

- Spring, Simpson, and Ferry creeks

How Do Tides Affect the Coquille River?

The Coquille River is a tidal-effect river. This means the ocean's tides affect how the river flows.

Tidal Influence Upstream

When the ocean has a high tide, the water at the river's mouth acts like a barrier. This slows down the river's flow. Even though more river water always flows out to the ocean than comes in with the tide, things floating on the surface, like logs and leaves, can sometimes float upstream. There is a delay between when the high tide happens in the ocean and when its effect is felt upstream. This delay changes depending on how far you are from the ocean. The tidal effect can be seen as far as Myrtle Point, which is about 28 to 30 miles (45 to 48 km) upriver.

Saltwater and Farming

Some saltwater from the ocean can also enter the river. In the past, this was not a big problem. But today, traces of salt can sometimes be found a few miles below the town of Coquille. This can be an issue for businesses along the river. Factories and mills need fresh water for their machines. Saltwater can cause rust or damage equipment.

The Coquille River valley is also an alluvial river valley. This means it was once a "drowned river valley," like a wide lake or river with a sandy bottom. The soil in the valley is very rich and good for growing plants. However, the changing water levels and winter floods make regular farming difficult. A special type of grass grows in the lowlands that can survive both dry periods and floods. There are also "tide-gates" along the river that can bring in water when needed. In the summer, many cattle graze on this lush grass.

What Is the History of the Coquille River?

In its natural state, the Coquille River's mouth moved around a lot. It could empty into the sea anywhere from Whiskey Run beach to Table Rock, a distance of several miles.

Making the River Mouth Safe

Early sailing ships found it dangerous to cross the sandbar at the river's mouth to reach the port at Bandon. The main channel might have moved or become too shallow since they last crossed it. To fix this, a sea captain named Judah Parker built a jetty. He used bundles of cedar branches wrapped in burlap and sank them into the mud, then added rocks. In the late 1890s, the government built stronger jetties to keep the channel in place. Huge rocks for the South Jetty came from blasting a nearby mound called Tupper Rock. The North Jetty is across the river and can be seen from the South Jetty.

The Coquille River Lighthouse

The Coquille River Lighthouse was built in 1896. It helped sailors find the dangerous sandbar at the river's mouth. The lighthouse was built on or near Rackleff Rock, a rocky obstacle in the channel. This rock later became part of the North Jetty. The lighthouse stopped being used in 1939 after the river channel was improved.

Bullards Beach State Park

The pioneer Hamblock and Bullards families once had ranches in this area. Their lands eventually became part of the Bullards Beach State Park. The old lighthouse building is still there today and is a popular place for tourists to visit.

Coquille River in Literature

The Coquille River was featured in an early science fiction book by Jules Verne. In his book The Begum's Millions, Verne imagined a perfect community called Ville-France. This fictional town was created in 1872 at the Coquille River's meeting point with the Pacific Ocean. This location was a little southwest of where the real town of Bandon is today.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |