Culture of the Tlingit facts for kids

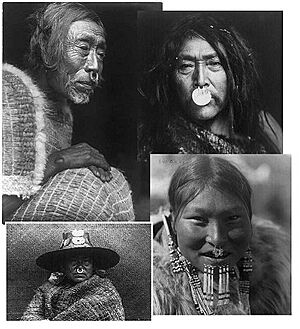

The Tlingit are an amazing Indigenous people from places like Alaska, British Columbia, and the Yukon. Their culture is rich and complex, just like many other groups along the Pacific Northwest Coast. They lived in areas with lots of natural resources, which made their lives easier in many ways.

Family and community connections are super important to the Tlingit. They also have a strong tradition of storytelling and public speaking. Being wealthy and having economic power showed status, but so did being generous and behaving well. These traits were signs of good upbringing and connections to important families.

Art and spiritual beliefs are part of almost everything in Tlingit culture. Even everyday items, like spoons or storage boxes, are often decorated. These decorations carry spiritual meaning and tell stories about their history.

Contents

Tlingit Family and Community Life

The Tlingit family system is based on the mother's side, which means children belong to their mother's family group. Their society is divided into two main halves, called moieties. These are the Raven (Yéil) and the Eagle/Wolf (Ch'aak'/Ghooch). The Raven moiety uses the raven as its main symbol. The Eagle/Wolf moiety might use a wolf, an eagle, or another strong animal, depending on where they live. Sometimes, people just call them the "not Raven" group.

Traditionally, people from one moiety could only marry someone from the opposite moiety. This helped keep the family lines strong and connected different groups. However, over the last century, this system has changed. Today, marriages between people from the same moiety or with non-Tlingit people are more common.

Within these moieties are smaller groups called clans (naa'). Clans are large family groups connected by shared history and family trees. They also own property together. Clan sizes vary, and some clans are found across all Tlingit lands, while others are in just a few villages. Most formal property among the Tlingit belongs to clans, not to individuals.

In the past, the father played a smaller role in raising his children. Instead, the mother's brother, the children's maternal uncle, took on many of these duties. He was from the same clan as the children and acted as a caretaker, teacher, and guide. Fathers often had a more fun and playful relationship with their children.

Beneath the clans are houses (hít). These are smaller family groups who used to live together in large communal homes. The physical house belonged to the clan, but the people living there were its keepers. Each house had a leader, called a hít s'aatí or "house master." This was usually an older male with high standing in the family. Very important hít s'aatí who were major community leaders were called aan s'aatí or aankháawu, meaning "village leader."

Early European explorers sometimes misunderstood this system. They expected one main "chief" for an entire village. But a Tlingit "house master" only had authority over his own household. A respected hít s'aatí could influence others, but he couldn't force them to do anything.

The hít s'aatí looks after the house property and much of the clan's property in his area. He might even call himself a "slave" to these valuable items because he doesn't truly own them. Instead, he's like a museum curator, deciding when items are used or displayed, but not selling or destroying them without consulting other family members. He also makes sure clan treasures are shown at potlatches, where their value and history are celebrated.

Historically, Tlingit marriages were often arranged. A man would move into his wife's house and become part of her household. He would help gather food and use his wife's clan resources. Children belonged to the mother's clan. Sometimes, marriages were arranged so a man married a woman from his father's clan (but not a close relative). This was seen as ideal because the children could then inherit wealth and prestige from their paternal grandfather.

Grandparents, especially grandfathers, often had a special bond with their grandchildren. They were known for spoiling them! A famous Tlingit story tells how Raven cleverly tricked his grandfather into giving him the moon, stars, and even the sun, just because he was a favorite grandchild.

Every Tlingit person belongs to a clan, either by birth or adoption. The relationship between a father and his children is warm and loving. This connection also strengthens the bond between their two clans. In times of sadness or difficulty, a Tlingit person can ask their father's clan for support, just as they would their own.

Clans also support each other through potlatches. These are special ceremonies, especially important after someone passes away. When a respected Tlingit person dies, their father's clan helps care for the body and arrange the funeral. The deceased's own clan is too sad to do these tasks. Potlatches are then held to honor ancestors and thank the opposite clans for their help during difficult times. This teamwork between clans is very important for the well-being of the Tlingit community.

Understanding Tlingit Property

In Tlingit society, many things are considered property that might seem unusual to others. This includes names, stories, speeches, songs, dances, special places like mountains, and artistic designs. These ideas are a bit like modern intellectual property laws, which protect creative works.

More familiar types of property include buildings, rivers, totem poles, berry patches, canoes, and artworks. For a long time, the Tlingit felt they couldn't protect their cultural properties from people who didn't respect them. But in recent years, they have learned to use modern laws to defend their rights, especially against the theft of clan designs.

Today, Tlingit society uses two main ideas of property. One comes from American and Canadian laws. The other is the traditional Tlingit concept. These two ideas can sometimes conflict, especially about who truly owns something or how it's passed down. This can cause disagreements within Tlingit communities and with outsiders.

The Tlingit mostly use their traditional property ideas during important ceremonies. These include events after someone dies, when building clan houses, or when raising totem poles. For example, Tlingit tradition says that personal property goes back to the clan if there are no direct family members to care for it. This is different from some other laws, but it shows how important the clan is in Tlingit life.

Many forms of art are considered property in Tlingit culture. It's not just about a specific drawing or carving. The ideas behind artistic designs are themselves property. If someone uses a design without permission and can't prove they own it, it's seen as taking something that belongs to another clan.

Stories are also owned by specific clans. Some stories are shared freely but are still known to belong to a certain clan. Other stories are private and can only be shared with a clan member's permission. However, some humorous tales, like many in the Raven cycle, are considered public domain. Using characters or situations from stories that belong to certain clans without permission is seen as disrespecting their property rights.

Songs are also clan property. When someone composes a song, it belongs to them until they pass away. Then, ownership usually goes to their clan. Some children's songs or lullabies are considered public domain. But any serious song, like a love song or a mourning song, is the sole property of its owner and cannot be sung or performed without the clan's permission.

Dances are also clan property, similar to songs. Since people from different clans often perform dances together, it's important to announce who gave permission for the dance and who the original creators or owners are.

Names are a special kind of property. Most names are inherited from a deceased relative and given to a living member of the same clan. Young children might get a temporary name that fits them or remembers an event. These newer names aren't as important as those passed down through many generations. Sometimes, names are "borrowed" from another clan to settle a debt and returned later.

Places and natural resources are also considered property. This includes salmon streams, herring spawning grounds, berry patches, and fishing spots. Some clans even own mountain passes because they had special trading relationships with other groups who lived beyond those passes.

The Tlingit lands in Southeast Alaska are divided among different clans. However, this doesn't usually stop people from gathering food or traveling. Clans often have agreements that allow almost anyone to harvest resources in most areas, as long as they show respect and don't take too much. This applies to relations within Tlingit society, but not always to interactions with governments or non-Tlingit individuals.

Potlatch Ceremonies

Potlatches (called koo.éex' in Tlingit) are important ceremonies. They are held for many reasons, such as births, naming ceremonies, marriages, sharing wealth, raising totem poles, and honoring leaders or those who have passed away.

A major event is the memorial potlatch, held about a year or two after someone dies. This ceremony helps the community heal and allows the deceased person's family to stop mourning. If the person was important, like a leader, their successor might be chosen at this potlatch. Members of the opposite moiety play a role by receiving gifts and sharing songs and stories. The memorial potlatch helps people deal with the sadness of death and feel more at peace about the afterlife.

Sometimes, food was burned during potlatches. People believed this would "feed" new totem poles, giving them spiritual energy.

Tlingit Art and Craftsmanship

Totem Poles: Stories in Wood

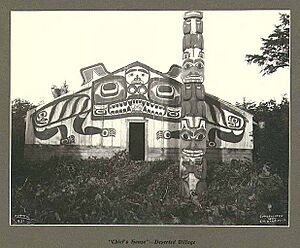

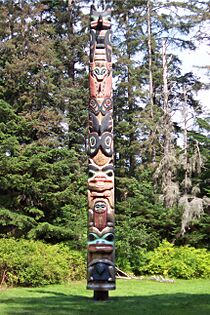

The Tlingit are famous for carving crests onto totem poles made from cedar trees. These poles usually tell a story, often featuring animals and other figures carved one above the other from top to bottom.

Totem poles were placed on the outside corners of traditional homes, helping to support the building. They were also sometimes put along shorelines.

When iron tools became available, Tlingit carvers could make even more totem poles. By the early 1800s, Tlingit villages had many poles, and important families often had large ones in front of their homes. To understand a totem pole, you needed to know the stories and legends it represented. The symbols and characters provided clues, but the full meaning came from shared knowledge. The Raven and the Wolf are two very important figures in Tlingit totem art. The Raven often appears as a clever hero in many Tlingit stories, having brought the sun, water, and fish to the land.

Totem poles also showed the power of a leader or family and honored those who had passed away. Some poles, called "Mortuary Poles," even held the ashes of a deceased family member in a carved wooden box placed inside the pole or a hollowed-out tree. Tlingit leaders would commission colorful totem poles to celebrate their achievements, social status, and wealth. Wealthy Tlingit families would plan for years to create large, impressive totem poles for major potlatches.

Tattoos and Body Art

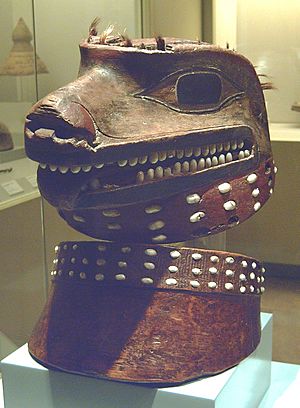

Both adult men and women, and children over 8 from important families, wore earlobe ornaments. These were often made from abalone shells, copper, wood, and bone, shaped into different designs. Men's earrings, called “Dis Yar Kuku,” were often half-moon shaped and showed various animals or patterns. As the Tlingit learned about metalworking, they started using silver more often instead of bone and wood. When a Tlingit person passed away, they were dressed carefully and given a nose ring called a "tunás".

The Tlingit traditionally painted their faces with white, black, and red colors. These paints, made with traditional methods, could stay on the body for months. They protected the skin from harsh winter weather and helped prevent snow blindness. In summer, they also helped keep away gnats and mosquitoes. More complex body paints were made by mixing fungi, ash, roots, clays, and charcoal. For quick use, charcoal was enough. Black was often used to show death, anger, sadness, and war. It was common for Tlingit people to blacken their faces with charcoal if they felt insulted or were in a conflict.

Tattooing, or Kuh Karlh “Mark” to the Tlingit, became popular through the Haida, who shared the practice with nearby Tlingit groups. An explorer in 1799 noted tattoos mostly on women's arms. However, tattooing was still very important in Tlingit society. It marked someone as belonging to a high-status family or household. The process was also expensive. The person getting tattooed paid the artist, usually a woman, with blankets and food. A needle, made of bone or metal, was used to pass blue-black stained sinew under the skin to create the designs. Young girls from wealthy Tlingit families were often tattooed at large potlatches.

Knives and Daggers

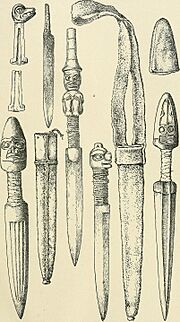

Tlingit metal daggers came in three main types: double-bladed, those with decorated handles (hafted-pommel), and blades made for trade. They used copper, iron, and steel for the blades. The guards of these weapons could be made from ivory, bone, wood, leather, or other metals. Daggers used for fighting had a leather strip, called a “thong,” extending from the top of the handle. Warriors would wrap this around their wrist to keep control of the weapon.

Daggers with artistic, non-bladed handles were called "hafted-pommel" blades. These often featured beautiful carvings of animals like ravens, bears, and other wildlife important in Tlingit culture. The art on Tlingit daggers became most complex in the early 1800s. Tlingit smiths added more designs, using copper for details like family crests and scenes. These daggers were symbols of status and authority. A more ornate weapon earned respect and was a valuable family heirloom passed down through generations. When firearms became common, the Tlingit dagger became less important for war, but it remained a powerful symbol of status.

Before trading with Europeans, copper was the main metal used by Indigenous peoples in Alaska. The Ahtna Athabascan people, who lived near the Copper River, controlled much of the copper trade. This led the Tlingit to build long-lasting trade relationships with the Athabascan people. Tlingit stories say that iron was first found as "drift iron" from a shipwreck. They then used it in their metalwork. When serious trade began with Europeans, an English captain named George Dixon noted that the Tlingit were very particular about their metal. They only wanted iron pieces between 8 and 14 inches long. In 1786, Jean-Francois de Galoup, the Comte de La Perouse, wrote that the Tlingit "had no great desire for anything but iron… Everyone had a dagger of it (iron) suspended from the neck."

Tlingit Warfare and Protection

Warriors of the Pacific Northwest

The Tlingit, Haida, and Eastern Aleuts were known as skilled warriors in the Northwest. These tribes often fought each other to gain resources. Tlingit warriors sometimes traveled hundreds of miles across the Pacific Northwest for these purposes. The Tlingit often had conflicts with the Haida and Tsimshian to the south, and sometimes with the Chugach and Alutiiq to the north.

Since there wasn't a central government to provide protection, individual groups of Tlingit warriors would unite for defense and offense. The main war season for most groups in the Northwest, including the Tlingit, was July (Tlexa). July had good weather, which was suitable for settling disputes and holding potlatches.

Tlingit warriors wore dense wooden helmets, along with neck protectors and visors to shield their faces. They also wore linen clothing and a leather jacket under wooden slat armor. This armor was sometimes brightly painted with Tlingit designs. When muskets were introduced, Tlingit armor makers added a layer of leather over the armor to help protect against musket balls. Wooden armor was also used by other tribes in the region, like the Haida and Gitxsan. Tlingit warriors carried their famous knives over their shoulder, along with spears, bows, and later, European muskets.

When the Tlingit fought European enemies, observers noted that the Tlingit quickly adopted European technologies to win battles. Their military forces were well-organized in their campaigns. The Russian American Company was a frequent opponent. Under the leadership of Alexander Baranov, the Russians sometimes used other Indigenous tribes, like the Unangax, who had disagreements with the Tlingit, to strengthen their forces in the Sitka Wars. In 1802, a group of Tlingit tribes defeated the Russian garrison at Sitka and took control of the area. They built their own forts and had cannons. At the Battle of Sitka, Russian forces eventually managed to drive the Tlingit from Sitka, but the Tlingit continued to challenge Russian forces and proved to be a strong fighting group.

Shamans and Spirits in Battle

Shamans were very important figures in Tlingit warfare. They guided much of the training, planning, and preparation for war parties. The Shaman would direct battles from a safe or hidden spot. For example, a Tlingit Shaman might position themselves in a canoe during battle, covering it with heavily reinforced mats. Spirits were central to these conflicts. Warriors would make war calls related to their crest spirit, asking for help or describing actions the spirit would take against the enemy. This back-and-forth between warring groups aimed to create fear and sometimes even ended conflicts without bloodshed. The main goal of most conflicts was to gain resources and tribute, so very bloody battles were often avoided unless absolutely necessary.

Unique Body Armor

The Tlingit used body armor made from Chinese cash coins. These coins were brought by Russian traders from Qing China between the 1600s and 1700s. The Russians traded these coins for animal skins, which they then traded with the Chinese for tea, silk, and porcelain. The Tlingit believed these cash coins would protect them from knife attacks and guns used by other Indigenous American tribes and Russians. Some Tlingit body armors were completely covered in Qing dynasty era cash coins, while others had them sewn in chevron patterns.

One Russian account from a battle with the Tlingit in 1792 stated that "bullets were useless against the Tlingit armor." However, this was likely due to the poor accuracy of Russian muskets at the time, rather than the coins themselves. The Chinese coins probably played a more important role in psychological warfare than in actual protection. Besides armor, the Tlingit also used Chinese cash coins on masks and ceremonial robes, like the Gitxsan dancing cape. These coins symbolized wealth and represented a powerful, faraway country. The cash coins used by the Tlingit were all from the Qing dynasty and had inscriptions from the Shunzhi, Kangxi, and Yongzheng emperors.

Notable Tlingit People

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |