Curt Flood facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Curt Flood |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

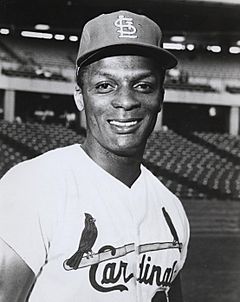

Flood with the Cardinals

|

|||

| Center fielder | |||

| Born: January 18, 1938 Houston, Texas |

|||

| Died: January 20, 1997 (aged 59) Los Angeles, California |

|||

|

|||

| debut | |||

| September 9, 1956, for the Cincinnati Redlegs | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| April 25, 1971, for the Washington Senators | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .293 | ||

| Home runs | 85 | ||

| Runs batted in | 636 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

|||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

|

|||

Curtis Charles Flood (January 18, 1938 – January 20, 1997) was an American professional baseball player. He was also an important activist for players' rights. He played as a center fielder for 15 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). His teams included the Cincinnati Redlegs, St. Louis Cardinals, and Washington Senators.

Flood was a three-time All-Star. He won the Gold Glove Award seven years in a row. He also had a batting average over .300 in six different seasons. He led the National League (NL) in hits in 1964. He also led the NL in singles in 1963, 1964, and 1968. Flood was also known for his excellent defense. He led NL center fielders in putouts four times and in fielding percentage three times.

Curt Flood became a key figure in baseball history. This happened when he refused a trade after the 1969 season. He took his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Even though he lost his legal challenge, his actions helped players unite. They fought against baseball's "reserve clause" and worked to gain free agency.

Contents

Becoming a Baseball Star

Curt Flood was born in Houston, Texas. He grew up in Oakland, California. In high school, he played outfield with future stars Vada Pinson and Frank Robinson. All three later signed professional contracts with the Cincinnati Reds. Flood graduated from Oakland Technical High School.

Starting His MLB Journey

Flood signed with the Cincinnati Reds in 1956. He played a few games for them in 1956 and 1957. However, the Reds had another great center fielder, Vada Pinson, ready to join the team. So, Flood was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in December 1957.

For the next 12 seasons, Flood was the main center fielder for the Cardinals. He was a strong defensive player from the start. His hitting improved greatly in 1961 when Johnny Keane became manager. He batted .322 that year. In 1963, he hit .302 and scored 112 runs. He also had career bests in doubles (34), triples (9), and stolen bases (17). He got 200 hits that year. In 1963, he also won the first of his seven Gold Glove Awards.

All-Star Seasons and World Series Wins

Flood was chosen for his first All-Star team in 1964. He batted .311 that season. He also led the NL in at-bats and tied for the most hits with 211. In the 1964 World Series against the New York Yankees, he helped the Cardinals win their first championship since 1946.

In 1965, Flood hit 11 home runs and had 83 runs batted in, while batting .310. He made the All-Star team again in 1966. That year, he did not make a single error in the outfield. He had an amazing error-free streak of 226 games. This was an NL record for an outfielder.

In 1967, Flood had his highest batting average at .335. He helped the Cardinals win another championship. In the 1967 World Series against the Boston Red Sox, he made important plays. He helped his teammate Lou Brock score runs in key games.

As a team co-captain in 1968, Flood had one of his best years. He was chosen for his third All-Star team. He finished fourth in the voting for the MVP award. He batted .301 and had 186 hits.

Challenging the Reserve Clause

Even with his great playing career, Curt Flood is most remembered for his actions off the field. He believed that Major League Baseball's "reserve clause" was unfair. This rule meant that players were tied to the team they first signed with for their entire career. This was true even after their contracts ended.

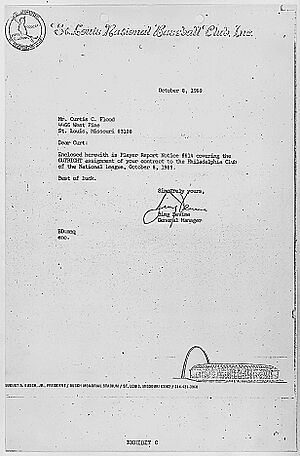

The Trade and Flood's Refusal

On October 7, 1969, the Cardinals traded Flood and three other players to the Philadelphia Phillies. Flood refused to join the Phillies. He said he didn't want to move his life to another city. He also mentioned the team's poor record and old stadium. Flood felt that he was being treated like property, not a person.

Flood was set to lose a lot of money if he didn't report. But after talking with players' union head Marvin Miller, he decided to take legal action.

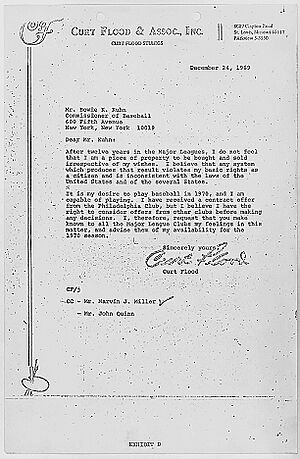

He wrote a letter to Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Flood asked the commissioner to declare him a free agent. He wrote:

- December 24, 1969

- After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

- It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

Flood was inspired by the civil rights movement of the 1960s. He felt that the reserve clause was an injustice.

The Supreme Court Case: Flood v. Kuhn

Commissioner Kuhn said no to Flood's request. He said the reserve clause was proper and part of Flood's contract. So, on January 16, 1970, Flood filed a lawsuit against Kuhn and Major League Baseball. He claimed they were breaking federal antitrust laws. Flood compared the reserve clause to slavery.

Important people like former players Jackie Robinson and Hank Greenberg spoke in court to support Flood. No active players testified, showing how divided players were on the issue.

The case, Flood v. Kuhn, was heard by the Supreme Court on March 20, 1972. Flood's lawyer argued that the reserve clause lowered wages and kept players stuck with one team for life. Baseball's lawyers said that if Flood won, it would cause chaos in the sport.

On June 19, 1972, the Supreme Court ruled 5–3 in favor of Major League Baseball. They based their decision on an older ruling from 1922.

Later Changes in Baseball Rules

Even though Flood lost his case, the players' union kept fighting the reserve clause. It was finally ended in December 1975 in a different case. In July 1976, the union and team owners agreed to a new contract that included free agency for players.

In 1998, the U.S. government passed the Curt Flood Act of 1998. This law removed baseball's special protection from antitrust laws. This protection had been in place for 75 years. The act did what Flood wanted: it stopped owners from having complete control over players' contracts and careers.

Flood also helped create the 10/5 Rule, also called the Curt Flood Rule. This rule says that if a player has been with one team for five years and played in MLB for ten years total, the team needs the player's permission to trade them.

Life After Baseball

After his lawsuit, Flood found it hard to play baseball again. Many people thought he would be "blackballed" (prevented from playing) by the league. Flood realized his career was likely over. He said, "You can't buck the Establishment."

Flood did not play at all in 1970. He received many angry letters from fans. In November 1970, the Phillies traded Flood to the Washington Senators. He signed a contract but only played 13 games in 1971. He batted .200 and left the team in April, then retired. He ended his career with a .293 batting average, 1,861 hits, and excellent defense. Later that year, Flood wrote a book called The Way It Is, explaining his fight against the reserve clause.

Retirement Activities

After retiring, Flood bought a bar in Palma, on the island of Majorca. He faced some financial challenges. He later returned to baseball as a broadcaster for the Oakland Athletics in 1978. In 1988, he became commissioner of a short-lived league called the Senior Professional Baseball Association. He also enjoyed painting.

His Legacy and Passing

On January 20, 1997, just after his 59th birthday, Curt Flood passed away in Los Angeles, California. He had developed pneumonia.

Before his death, Flood's impact was recognized in Congress. A bill was introduced to give baseball players the same antitrust protections as other professional athletes. The bill was numbered HR 21, which was Flood's uniform number.

Flood's fight for free agency was shown in Ken Burns' documentary series Baseball. In 1999, he was honored by the Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals. In 2020, many members of Congress and other sports unions asked the Baseball Hall of Fame to admit Flood.

Personal Life and Health

Flood was married twice and had five children. His first marriage was to Beverly Collins from 1959 to 1966. They had five children: Debbie, Gary, Shelly, Scott, and Curt Flood, Jr. Flood later married actress Judy Pace in 1986. They remained married until his death. In 1995, Flood was diagnosed with throat cancer. He had treatments and surgery, which made it hard for him to speak.

See also

- List of St. Louis Cardinals team records

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |