Divine Caste facts for kids

The Divine Caste, known as "la casta divina" in Spanish, was a very powerful group of families in Yucatán, Mexico. They controlled the economy and politics of the region from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s. This special group had about twenty families of Spanish descent who managed the henequen business. Their control made Yucatán the richest and most industrialized state in Mexico during the early 20th century.

During Yucatán's "Golden Age," from about 1870 to 1920, henequen made up almost 20% of all of Mexico's exports. It was the country's second most valuable export, after precious metals. Unlike other places, business owners in Yucatán kept control of their land and factories. Because of the henequen boom, Mérida, the state capital, had more millionaires per person than any other city in the world.

By the early 1900s, the Divine Caste started to have disagreements among themselves. This was a power struggle between the old, powerful families and Olegario Molina. Molina wanted to control the entire henequen business. He was working for J. P. Morgan and International Harvester, a huge American company. After the big changes of the Mexican Revolution, the Divine Caste lost much of its political power. However, the families' descendants continued to be active in business. They are also believed to have helped start the National Action Party (PAN), a center-right political party.

Contents

A Look Back in Time

During the time when Spain ruled Mexico, people of Spanish descent born in the Americas, called criollos, held a special position. They formed a powerful group that owned large estates called latifundios. In Yucatán, some important families, like the Peón and Cámara families, became very wealthy even before Mexico became independent. They owned a lot of land and often married within their own group to keep their power strong.

After Mexico gained independence, it was easier for people to move up in society economically. But it was still hard to gain political power. In central Mexico, the criollo elite kept their money but shared political power with mestizos (people of mixed European and indigenous descent). This helped make the new country seem fair. But in Yucatán, the criollo elite kept control of everything: politics, money, and social life.

The Caste War of Yucatán was a major conflict from 1847 to 1901. It was a long and violent uprising by the native Maya people against the ruling criollo elite and their mestizo friends. Even with this war going on, the henequen business surprisingly grew stronger.

The Henequen Boom

Henequen and sisal are plants that grow naturally in Yucatán. Their strong fibers were used for many things, especially to make rope and twine. These were in high demand during the Industrial Revolution. Henequen fiber was strong and useful for industries like shipping, construction, and agriculture. Yucatán was perfect for growing henequen because of its climate and large areas of fertile land.

In the mid-1800s, Eusebio Escalante Castillo helped develop the henequen industry in Yucatán. He got money from Thebaud Brothers, an investment bank in New York City. The henequen business did very well, making more products and selling them abroad. Yucatán became the world's top henequen producer, almost having a complete control over the market. Countries like the United States and industrialized nations in Europe wanted a lot of henequen fiber. This brought huge profits to Yucatecan landowners and business people. It also helped the region grow socially and economically.

The Caste War and Henequen

The Caste War caused many problems in Yucatán, affecting social and economic life. However, the henequen plantations managed to stay productive and profitable. One main reason was where the fighting happened. The Caste War was mostly in the eastern and southern parts of the Yucatán Peninsula, where most Maya communities lived. The henequen plantations, though, were mainly in the northern and western regions. These areas were less affected by the war. They continued to grow and produce henequen.

Wealthy criollo families often owned the plantations in the northern and western regions. They were able to protect their properties from attacks. They also got support from the government, which helped them keep their henequen businesses running.

Also, some Maya communities who were not part of the rebellion kept working on the henequen plantations. They often did this because they needed the money. The henequen industry offered jobs and a way to earn a living. The plantations provided a source of income and stability, even during the difficult times of the war.

Who Were the Henequen Kings?

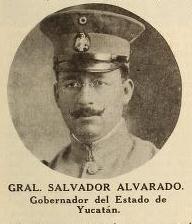

The money made from the henequen industry was held by a small group of criollo families. These families were often related to each other. People who criticized this powerful group called them the "fifty henequen kings" or the "henequen aristocracy." Salvador Alvarado called them the "divine caste."

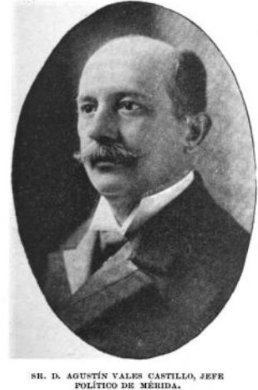

Between 1880 and 1915, there were about 1,000 henequen farms in Yucatán. About 850 of these had machines to process the fiber. Around 400 families owned these farms. But a smaller group of 20 or 30 families owned most of the land. They produced half of all the henequen and controlled almost 90% of its export. They also controlled the region's politics. This group was an oligarchy, meaning a small group of people held all the power. Some of the most important members were Eusebio Escalante Castillo, Eusebio Escalante Bates, Carlos Peón Machado, Pedro Peón Contreras, Leandro León Ayala, Raymundo Cámara Luján, José María Ponce Solís, Enrique Muñoz Arístegui, Olegario Molina Solís, and Avelino Montes.

These families were so dominant in henequen production and trade that they became some of the richest in the Americas. They traveled to fancy places and learned other languages. They were a very cultured group of people.

Carlos Peón, a politician and landowner, was the Governor of Yucatán from 1894 to 1897. He believed in economic liberalism, which means he wanted free markets and less government control. He focused on growing industries, especially henequen production and export. The governors after him, Francisco Cantón and Olegario Molina, also supported and took part in the henequen industry.

The fancy social clubs in Mérida, like "El Liceo" and "La Lonja Meridiana", were only for wealthy business owners, landowners, and politicians of European descent. They did not allow outsiders, even rich Lebanese business people. "La Lonja Meridiana" was the most exclusive club.

Changes and Challenges

In 1902, after the Caste War ended, President Porfirio Díaz wanted to show his power. He did not let Francisco Cantón become governor of Yucatán. Instead, Díaz chose Olegario Molina, who was a liberal. Many people in Yucatán protested this decision.

That same year, President Díaz made two other decisions that hurt the area. He separated Quintana Roo from Yucatán and gave up Mexico's claim to Belize. These actions also caused opposition from many people in Yucatán.

Francisco Cantón had to leave public life and sold all his businesses to Eusebio Escalante. The Escalante family was one of the wealthiest families in Mexico around 1900 because of their henequen business. But after 1902, Olegario Molina became a strong rival. Even though Molina started poor, he became very rich with the help of President Díaz and his powerful advisors, known as "los Científicos." Molina became even more powerful when he was the Governor of Yucatán from 1902 to 1906. Later, he became the Secretary of Commerce and Industry in the Mexican government from 1906 to 1911.

In October 1902, Molina met with Cyrus McCormick, who started International Harvester. They made a secret deal. The American company agreed to only buy henequen sold by Molina's company. Molina would be the middleman between the henequen farm owners and the American markets. In return, Molina promised to try his best to lower the price of henequen fiber. McCormick would also tell him what prices to pay.

This secret deal and Molina's political power made him the biggest landowner and henequen producer in the state. But he also became the main enemy of other landowners. Molina wanted to gain complete control, and his wealth grew very fast. This bothered a group of wealthy families who had owned land and cattle for a long time. They were good at adapting to new economic times. This group included Eusebio Escalante, José María Ponce, Carlos Peón, and Raymundo Cámara.

After a financial crisis in 1907, the Escalante trading company faced big problems. Molina used this chance to his advantage. He became the main exporter of henequen by purposely lowering prices to control the market. Molina used his political power, gave special favors to friends, and used business practices that created a monopoly to make his business empire stronger and get rid of his competitors. By 1907, Olegario Molina was the most important person in the Yucatecan elite.

Because Molina gained so much power in the state's economy and politics, many landowners from the traditional families (like Cámara, Peón, Escalante, Ponce) had to join together to challenge him. They formed the first association of henequen landowners. Their main goal was to protect themselves from Olegario Molina and his son-in-law, Avelino Montes. Molina had a lot of economic and political power, which caused problems between the landowners' associations and the local and federal governments.

In 1910, Francisco I. Madero, a rich landowner from northern Mexico, started a movement to overthrow the dictator Díaz. Many Yucatecan landowners who felt threatened by Olegario Molina supported this revolution. After Madero's revolution in 1910 and José María Pino Suárez becoming governor of Yucatán in 1911, the relationship between these landowners and the government changed. However, Pino Suárez's time as governor was short. He resigned to become the Vice-President of Mexico. His brother-in-law, Nicolás Cámara Vales, became the next governor. Both men were close to the traditional landowning families.

During his time as governor, Nicolás Cámara Vales created the Henequen Market Regulatory Commission in 1912. This group aimed to control prices and help landowners sell their products more easily. This would reduce the powerful control that International Harvester wanted. But in February 1913, Madero's government was overthrown in a military coup. Governor Cámara Vales was forced to resign by the new military leader, General Victoriano Huerta.

In 1915, after Huerta's government fell, Venustiano Carranza, a revolutionary politician, became President of Mexico. Soon after, Carranza sent General Salvador Alvarado to Mérida. Alvarado's goal was to spread the socialist ideas of the Mexican Revolution in Yucatán. Yucatán was far from the rest of the country and had not been greatly affected by the revolution's radical changes until then. Both Molina and Pino Suárez followed older liberal ideas and did not like socialism. But with Alvarado's arrival in 1915, socialism could no longer be avoided in Yucatán. It became a major part of Mexican politics until the 1980s.

General Alvarado tried to end the Divine Caste's power over politics, economy, and society. The most exclusive club linked to the Yucatecan elite was "La Lonja Meridiana." This club brought together the most important people in Mérida. It was known for its fancy parties and was only for white (criollo) members and their guests. This was a big contrast to the ordinary mestizo people watching from the streets.

However, one evening in March 1916, the beautiful halls of La Lonja Meridiana heard not only the usual music but also the footsteps of mestizos on the marble floors. The French mirrors, which usually showed off expensive clothes and jewelry from Paris, now showed the suits and rosaries of mestiza women. General Alvarado must have enjoyed this symbolic victory of the mestizo people over the powerful elite. The members of La Lonja Meridiana must have been horrified, seeing it as a clear sign that times were changing because of the Revolution.

The End of an Era

During the 1930s, Lázaro Cárdenas, the socialist President of Mexico, took over the Haciendas of Yucatán. The haciendas stopped existing as private farms. They became ejidos, which are community-owned lands. This action finally broke the strong control that the Divine Caste once had over the region.

Influence Today

After the Mexican Revolution, the descendants of the Divine Caste mostly stepped back from direct politics. But they continued to be involved in other areas of public life, like business and diplomacy. Like the rich business owners in Monterrey, it is thought that the descendants of the Yucatecan elite helped create and grow the center-right National Action Party (PAN). In 2001, after almost 90 years of revolutionary governments, Patricio Patrón Laviada, a PAN politician and a descendant of two important families linked to the Divine Caste, became the Governor of Yucatán. A similar story can be seen with Carlos Castillo Peraza, a Yucatecan thinker who helped shape the PAN party's ideas.

A study from 2018 shows how descendants of the Divine Caste still have influence in social groups. Magazine photographers and bouncers are reportedly told to choose certain people, especially descendants of influential families like the Cámara family, to photograph or to let into exclusive nightclubs first. This shows that a social hierarchy based on wealth and status still exists. People from certain families are seen as "opinion leaders" who set trends for others to follow. For example, if someone famous like Juan Cámara drinks a certain brand, others might want to drink it too to be like him.

See also

In Spanish: Casta divina para niños

In Spanish: Casta divina para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |