Douglas Corrigan facts for kids

Douglas Corrigan (born January 22, 1907 – died December 9, 1995) was an American pilot from Galveston, Texas. He became famous in 1938 for a flight that earned him the nickname "Wrong Way" Corrigan. After flying across the United States from Long Beach, California, to New York City, he took off from Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York, and landed in Ireland. His flight plan said he was supposed to fly back to Long Beach. Corrigan said he made a mistake because of thick clouds and bad light, which made him misread his compass. However, he was a very skilled aircraft mechanic and had even helped build Charles Lindbergh's famous plane, the Spirit of St. Louis. He had also made many changes to his own plane, getting it ready for a long flight across the ocean. He had been told "no" when he asked for permission to fly nonstop from New York to Ireland. Because of this, many people thought his "mistake" was actually on purpose. But he never said he flew to Ireland on purpose.

Contents

Early Life and Learning to Fly

Douglas Corrigan was born Clyde Groce Corrigan, named after his father, who was a construction engineer. His mother was a teacher. The family moved around a lot. After his parents divorced, Douglas settled in Los Angeles with his mother, brother Harry, and sister Evelyn. He left high school and started working in construction.

In October 1925, Corrigan saw people taking short airplane rides near his home. He paid $2.50 for his first ride. Just a week later, he started taking flying lessons. When he wasn't flying, he spent time watching and learning from airplane mechanics. After 20 lessons, he flew an airplane by himself for the first time on March 25, 1926.

Working with Airplanes

The company where Corrigan learned to fly, Ryan Aeronautical Company, hired him in 1926. He worked at their factory in San Diego. Corrigan helped build Charles Lindbergh's famous plane, the Spirit of St. Louis. He put together the wing and installed the fuel tanks and control panel. Corrigan and another worker made the wing longer to help the plane lift better. He was even there when Lindbergh took off from San Diego to start his historic flight.

After Lindbergh's successful flight across the Atlantic Ocean, Corrigan wanted to do the same thing. He decided his goal would be Ireland. He even talked to friends about flying there without official permission. When Ryan Aeronautical moved away in 1928, Corrigan stayed in San Diego. He worked as a mechanic for a new flying school called Airtech School. With many students flying every day, Corrigan could only practice flying during his lunch break.

During his short flights, Corrigan loved to do exciting stunts in the air. His favorite trick was the "chandelle," where he would make the plane climb and turn sharply. He would do many of these in a row, starting close to the ground. The company didn't like this and told him not to do stunts in their planes. So, Corrigan just flew to a different field where his bosses couldn't see him.

Corrigan moved between different jobs as an aircraft mechanic. He used the planes at his jobs to get better at flying. In October 1929, he earned his transport pilot's certificate, which allowed him to carry passengers. In 1930, he started a passenger service with a friend, flying between small towns on the East Coast. The best part of their business was putting on airshows, called "barnstorming," to get people interested in short plane rides. After a few years, Corrigan decided to go back to the West Coast. In 1933, he bought a used 1929 Curtiss Robin plane for $310. He flew it home and went back to being a mechanic. He also started changing his Robin plane to get it ready for a flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

The "Wrong Way" Flight

Corrigan put a new engine into his plane, made from parts of two old engines. This new engine gave the plane more power. He also added extra fuel tanks. In 1935, he asked the government for permission to fly nonstop from New York to Ireland. His request was turned down. Officials said his plane wasn't safe enough for a nonstop flight across the ocean, even though it was approved for shorter cross-country trips.

For the next two years, Corrigan kept changing his plane and asking for permission, but he never got it. By 1937, after many changes, his plane's license was not renewed because it was considered too unstable to fly safely. In his book, Corrigan wrote about how frustrated he was with the officials. Many people believe he then decided to make the flight without permission.

Even though he never said it, he seemed to plan to arrive in New York late. This way, he could refuel his plane and leave for Ireland after airport officials had gone home. But he had mechanical problems on his flight to New York, which made it take nine days. This delay meant he missed the "safe weather window" for flying across the Atlantic, so he went back to California. He named his plane Sunshine after this trip. However, government officials told California airports that Sunshine was not safe to fly, and it was grounded for six months.

On July 9, 1938, Corrigan flew from California to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York, again. He had fixed the engine, spending about $900 in total on the plane. He got a special experimental license and permission for a flight across the country, with a chance to fly back. His plane, the Robin, flew at about 85 miles per hour to save fuel. The flight to New York took him 27 hours. Saving fuel became very important near the end of the flight because gasoline started leaking, filling the cockpit with fumes.

When he arrived at Floyd Bennett Field, Howard Hughes was also there getting ready for his own flight around the world. Corrigan decided that fixing the fuel leak would take too long for his plan. His official flight plan said he would return to California on July 17. Before taking off, Corrigan asked the airport manager, Kenneth P. Behr, which runway to use. Behr told him to use any runway, as long as he didn't take off heading west, towards the main office building. In Corrigan's book, he said Behr wished him "Bon Voyage" before he took off, which might have been a hint about Corrigan's real plans. At 5:15 in the morning, Corrigan took off with 320 gallons of gasoline and 16 gallons of oil. He headed east from the 4,200-foot runway at Floyd Bennett Field and just kept going. (Behr later said publicly that he didn't know what Corrigan was planning.)

Corrigan said he realized his "mistake" after flying for about 26 hours. This doesn't quite match his other claim that after 10 hours, his feet felt cold because the cockpit floor was wet with gasoline from the leak. He used a screwdriver to poke a hole in the floor so the fuel would drain away from the hot exhaust pipe, which could have caused an explosion. If he truly didn't know he was over the ocean, he probably would have landed at this point. Instead, he said he made the engine go almost 20% faster, hoping to finish his flight sooner.

He landed at Baldonnel Aerodrome in County Dublin, Ireland, on July 18. The flight took 28 hours and 13 minutes. All he had to eat was two chocolate bars, two boxes of fig bars, and a quart of water.

Corrigan's plane had fuel tanks mounted in the front, so he could only see out of the sides. He had no radio, and his compass was 20 years old. A journalist named H. R. Knickerbocker met Corrigan in Ireland after he landed. In 1941, he wrote:

You might say that Corrigan's flight wasn't as exciting as Lindbergh's, which was the first solo flight across the ocean. Yes, but in another way, the flight of this unknown little Irishman was even braver. Lindbergh had a plane specially built, the best money could buy. He had lots of money helping him, and friends to assist him at every step. Corrigan had only his own dream, courage, and skill. His plane, a nine-year-old Curtiss Robin, looked like the worst old car.

When I looked at it at the Dublin airport, I truly wondered how anyone could be brave enough to even fly in it, let alone try to fly across the Atlantic. He built it, or rebuilt it, almost like a kid would build a scooter from a soapbox and old roller skates. It looked exactly like that. The front of the engine cover was a mess of patches that Corrigan himself had soldered together in a crazy pattern. The door where Corrigan sat cramped for twenty-eight hours was held together with a piece of baling wire. The extra gasoline tanks Corrigan put in left him so little room that he had to sit bent forward with his knees squeezed, and not enough window space to see the ground when landing.

Aviation officials needed 600 words to list all the rules Corrigan broke during his flight. Even though Corrigan broke so many rules, he only received a small punishment: his pilot's license was taken away for 14 days. He and his plane returned to New York on a ship called the Manhattan. They arrived on August 4, which was the last day of his license suspension. His return was met with huge celebrations. More people came to his Broadway ticker-tape parade in New York than had celebrated Lindbergh. He also had a parade in Chicago. Later, he even met with President Roosevelt at the White House.

Later Life and Legacy

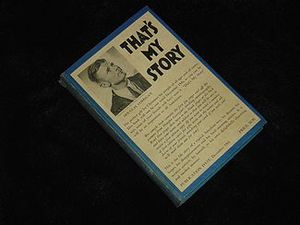

Corrigan wrote his autobiography, That's My Story, just a few months after his flight. It was published on December 15, 1938, in time for Christmas. He also promoted "wrong-way" products, like a watch that ran backward. The next year, he starred as himself in a movie about his life called The Flying Irishman (1939). He earned $75,000 from the movie, which was like 30 years of pay from his mechanic jobs. Although he didn't immediately admit his flight was on purpose, Charles Lindbergh wrote a friendly four-page letter to Corrigan in 1939 after Corrigan sent him a copy of his book.

In a letter to a fan in 1940, Corrigan said he had "no hobbies except working on airplanes or machinery." When the United States entered World War II, he tested bomber planes and flew for the Ferry Command, which was part of the Air Transport Command. In 1946, he ran for the U.S. Senate as a member of the Prohibition Party, but he received less than 2% of the votes. After that, he worked as a commercial pilot for a small airline in California.

Corrigan stopped flying in 1950 and bought an 18-acre orange grove in Santa Ana, California. He lived there with his wife and three sons until he passed away on December 9, 1995. He didn't know anything about growing oranges, but he said he learned by watching his neighbors. His wife died in 1966. Corrigan then sold most of his orange grove for new houses, keeping only his ranch-style house. One of the streets in the new neighborhood is named after him. He became more private after one of his sons died in a plane crash in 1972. However, in 1988, he joined the 50th anniversary celebration of his famous "wrong way" flight. He allowed people to get his plane, the Robin, out of its hangar. The plane was put back together, and its engine ran successfully. Corrigan was so excited that the organizers put guards near the plane's wings while he was at the show. They even thought about tying the plane's tail to a police car to stop him from taking off in it! Later, Corrigan became secretive about where the plane was. People rumored that he had taken it apart and stored it in different places to prevent it from being stolen.

Even up until his death, Corrigan always said that his flight across the Atlantic was an accident. In October 2019, Corrigan's Curtiss Robin plane was moved to the Planes Of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California, where you can see it on display today.

Among people who study aviation history, Corrigan is remembered as one of the brave pilots who made early flights across the ocean. When he died in 1995, he was buried at Fairhaven Memorial Park in Santa Ana. His memorial is a small flat stone with a copy of his signature on it.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Douglas Corrigan para niños

In Spanish: Douglas Corrigan para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |