Dudley Canal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dudley Canal |

|

|---|---|

The end of the No. 2 Line near Hawne Basin in 1987

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Locks | 12 (originally 14) |

| Original number of locks | 14 |

| Status | part navigable |

| Navigation authority | Canal and River Trust |

| History | |

| Original owner | Dudley Canal Company |

| Date of act | 1776 |

| Geography | |

| Connects to | Birmingham Canal Navigations |

The Dudley Canal is a canal that goes through Dudley in the West Midlands area of England. It's part of a big network of waterways in England and Wales. This canal is also a key part of the popular Stourport Ring route for narrowboats.

The first short part of the canal opened in 1779. It connected to the Stourbridge Canal. Later, in 1792, the Dudley Tunnel linked it to the Birmingham Canal system. Soon after, work began on a new section called Line No. 2. This line went through another long tunnel called Lapal and reached the Worcester and Birmingham Canal. It was finished in 1798. However, a lot of trade didn't happen until the Worcester and Birmingham Canal was completed in 1802.

In 1846, the Dudley Canal company joined with the Birmingham Canal Navigations. This led to many improvements. One big change was the Netherton Tunnel. It was similar in length to the Dudley Tunnel but much wider. It even had paths on both sides for horses and was lit by gas. This was the last canal tunnel ever built in England.

Over the years, the canal faced big problems because of coal mining. The ground above the canal would sink, which is called subsidence. The Lapal Tunnel was often affected by this. In 1894, a part of the canal near Blackbrook Junction fell into old mine workings. The route was fixed, but a nearby short section called the Two Locks Line was closed in 1909. The Lapal Tunnel also closed in 1917. Most of the Dudley Canal was closed in the 1960s. But then, a group formed, which became the Dudley Canal Trust. They worked hard to restore the canal. The Dudley Tunnel was finally reopened in 1973. The Lapal Tunnel is still closed today. A group called the Lapal Tunnel Trust now plans to create a surface route instead of reopening the tunnel.

Contents

History of the Dudley Canal

The first canal connecting Birmingham to the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal was the Birmingham Canal. This canal joined the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal near Wolverhampton. People wanted the Dudley Canal to help transport coal from mines near Dudley to Stourbridge. There, the coal would be used by factories. Limestone and ironstone were other important goods to move.

In February 1775, a meeting was held in Stourbridge. Robert Whitworth was asked to survey a route for the canal. The main person pushing for the canal was Lord Dudley. The planned route went from Dudley to Stourton. A bill (a proposed law) was put before Parliament. But the Birmingham Canal Company opposed it, so the plan was withdrawn. The promoters then split the canal into two parts. They presented bills for the Stourbridge Canal and the Dudley Canal. Both became Acts of Parliament (laws) on 2 April 1776, even with more opposition from Birmingham.

Thomas Dadford, Sr. became the engineer for the project. He worked on it until 1783. The Dudley Canal was planned to meet the Stourbridge Canal at the bottom of the Black Delph locks. The law allowed the company to raise £7,000. This money was collected by July 1778, but it wasn't enough. The company asked shareholders for more money, raising £9,200. Construction finished by June 1779. However, not much traffic used the canal until the Stourbridge Canal was completed in December of that year.

Building the Dudley Tunnel

In 1784, the Stourbridge and Dudley companies wanted to connect to the Birmingham Canal. This would mean building more locks at Park Head. It also required a tunnel to link to Lord Dudley's existing mining tunnel, which met the Birmingham Canal at Tipton. The Birmingham company agreed. But they charged high tolls for boats using the new connection. This was to make up for money they would lose from goods that used to travel a different route. Lord Dudley agreed to sell his tunnel to the Dudley Canal Company. He never received payment, as the benefits of the new canal were seen as enough.

A new law was passed in July 1785 to allow the work. John Snape and John Bull surveyed the route. Thomas Dadford checked their work and became a consulting engineer. Abraham Lees was the manager on site. John Pinkerton got the main contract for the tunnel. It was planned to be about 9.25 feet (2.8 meters) wide. It would have 7 feet (2.1 meters) of headroom and 5.5 feet (1.7 meters) of water. The contract said it should be finished by March 1788.

In 1787, Pinkerton's work was not good enough, and construction stopped. Dadford was paid off, and Pinkerton had to pay back some money. Work restarted with Isaac Pratt in charge. Lees stayed in his role. In May 1789, more problems arose. It was found that the tunnel was not straight. Pratt resigned. Josiah Clowes was hired to finish the project. He completed the tunnel and built a new connection to the Birmingham Canal at Tipton. The tunnel officially opened on 15 October 1792.

Line No. 2: The New Extension

Right after the first tunnel was finished, a meeting was held in Birmingham in August 1792. They proposed a new canal from Birmingham to the coal mines at Netherton. The canal company then suggested their own similar canal. After talks with the Worcester and Birmingham Canal, it was agreed to build this new line. It would be at the same level as the Dudley Canal at Park Head.

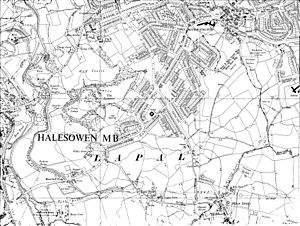

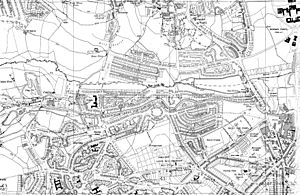

This new section needed a very long tunnel at Lapal, about 3,795 yards (3,470 meters) long. It also needed a shorter tunnel at Gosty Hill, about 537 yards (491 meters) long. Another short tunnel was planned at Halesowen, but it became an open cut with a bridge instead. The new canal would be about 10.8 miles (17.4 km) long. John Snape surveyed the route. Despite objections from other canal companies, a new law was passed in 1793. The Stratford-upon-Avon Canal was approved soon after. This canal would connect to London.

The original canal was renamed "Line No. 1." The new section became "Line No. 2." It linked the canal at Park Head Junction (near Netherton) to Halesowen. From there, it went through the tunnel at Lapal to the Worcester and Birmingham Canal at Selly Oak, Birmingham.

Work began in early 1794 with Josiah Clowes as engineer. Clowes died in 1796. William Underhill then managed the project for a year. Robert Whitworth checked the work and was happy with it. Underhill continued to manage the tunnel and an aqueduct. Benjamin Timmins managed the rest of the project. The section from Netherton to Halesowen was built about 1 foot (0.3 meters) too high. This was fixed, and the wharf at Halesowen opened in early 1797.

Building the tunnels was very hard. Thirty shafts were dug to allow many teams to work at once. Much of the route went through sand. Large amounts of water had to be pumped out using three steam engines. The new route was completed on 28 May 1798. Lord Dudley, who had led the company for 22 years, resigned. The company's money had grown a lot, but no profits had been paid out yet. Not many boats used the new tunnel until 1802. That's when the Stratford Canal provided a link to the Warwick and Birmingham Canal, which connected to London. The first profit payment to shareholders was made in 1804.

Decline of the Canal

The original canal line at Bumble Hole changed. It became the Bumble Hole Branch Canal and Boshboil Arm after a part of the canal collapsed. The two-locks line had problems with the ground sinking for many years. It was closed in March 1909 and later filled in. Today, this area is an industrial estate. Only the junctions, bridges, and a few yards of water remain.

After collapsing many times, the Lapal Tunnel was closed in June 1917. A short part of the canal remained open between Selly Oak and a brick works at California until 1953. After that, it was drained and filled in.

Restoring the Dudley Canal

After the canal was not used much following its nationalization in 1948, people started suggesting it should be restored. This idea came from the Inland Waterways Protection Society (IWPS) in 1959. However, in 1961, the British Transport Commission planned to close the Dudley Canal and Tunnel right away. There were no plans to save the route for future restoration. Both the Inland Waterways Association and the IWPS protested, but the canal closed in 1962.

Despite the closure, the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal Society explored the tunnel in 1963. After this, a Dudley Tunnel Committee started running boat trips through it. These trips became very popular. The Committee became the Dudley Canal Tunnel Preservation Society in 1964. It eventually became the Dudley Canal Trust in 1970.

In June 1970, a government committee called the Inland Waterways Amenity Advisory Council made recommendations. They suggested that the Dudley Canal and eight other canals should be brought back into use for boats. The Waterways Recovery Group, formed in 1970, started working on the canal that year. They helped people learn about the canal and its potential. In December 1970, a report suggested that much of the Birmingham Canal system should be kept. The Dudley Canal was in a group where local councils should help with restoration plans. This plan was adopted for the Dudley Tunnel Branch.

The Dudley Canal Trust began restoring the canal. In September 1971, they organized an event called "Dudley Dig and Cruise." Over 600 people helped clear a lock chamber and two lock sections of rubbish. In early 1972, Dudley Corporation said they would pay half the cost of restoration. They also planned to improve the area around the Park Head end of the Tunnel. About 50,000 tons of mud were removed from the canal. The locks reopened later that year. The Dudley Tunnel reopened at Easter 1973. About 14,000 visitors came to the opening ceremony.

A short branch north of the tunnel was restored in 1977. This was part of the Black Country Museum project. Money for this came from a scheme to provide work and training for unemployed people. The Trust used the museum as a base for their electric trip boat. By then, over 25,000 people had taken trips into the tunnel since 1964.

Plans for the No. 2 Line moved forward in 1980. A boat rally was held at Hawne Basin. This was an old railway interchange where tubes were moved from boats to trains. The railway had closed in 1967, and the basin had not been used since. But thirty boats came to the rally. The Combeswood Canal Trust made plans to turn it into a marina.

Part of the Lapal Tunnel was uncovered when the M5 motorway was built in the 1960s. The empty space was filled with concrete. The Lapal Canal Trust is working to restore parts of the lost canal. They plan to build a completely new route over the hill through Woodgate Valley Country Park instead of reopening the tunnels.

In February 2012, plans for improving the Selly Oak area were submitted. These plans included a navigable section of canal. It would go from a new connection with the Worcester and Birmingham Canal to the Harborne Lane bridge. This section follows the route of the old Dudley Canal.

On 28 February 2016, after part of the Harborne Lane Wharf was dug out again, a canoe paddled by a member of the Lapal Canal Trust became the first boat since 1953 to travel along the eastern part of the canal. This section goes through Selly Oak Park and still has water. Members of the trust thought this might be the first boat to go past Harborne Lane Wharf since the brickworks at the eastern end of the Lapal Tunnel closed in 1926. Pictures were shared on the Lapal Canal Trust's website.

Route of the Canal

The Dudley Canal connects directly to the Stourbridge Canal at the bottom of the eight Delph Locks. These are often called the Nine Locks, even though they were rebuilt as eight in 1858. There's a well-restored stable building near lock 3. Also, a Grade II listed (meaning it's historically important) lock keeper's house is nearby. It was built in 1779.

Above the locks, the canal passes the Merry Hill Shopping Centre. This center was built where the Round Oak Steelworks used to be. Even though it closed over 100 years ago, a cast-iron footbridge from 1858 still carries the towpath over the old entrance to the Two Locks Line. The canal then goes on an embankment (a raised bank) to Blowers Green Lock. This is the deepest lock on the Birmingham Canal Navigations. It replaced two older locks that were affected by the ground sinking. A pumphouse managed by the Dudley Canal Trust is nearby.

At Park Head Junction, Line No. 2 turns off to the south-east. But the original line continues through three locks. It then reaches a junction with the remains of the Pensnett Canal and the Grazebrook Arm. From there, it enters the southern entrance of Dudley Tunnel. At the other end of the tunnel is the Black Country Museum. This museum offers boat trips into the tunnel and the old mines connected to it.

Following Line No. 2 from Park Head Junction, the canal goes around Netherton Hill. There are mass graves for cholera victims in St. Andrew's churchyard here. After that, it goes through a cutting (a channel dug through the ground). This cutting was made in 1838 for the Lodge Farm Reservoir. Brewins Tunnel was built here, but its roof was removed after 20 years. A short branch managed by the Withymoor Island Trust is on the west bank and is used for mooring boats.

Beyond that, the Bumble Hole Branch partly goes around Bumble Hole. This is a water-filled old clay pit. This used to be the main canal line. But the raised route that cuts off the loop was built as part of the Netherton Tunnel project. Another part of the old loop, the Boshboil Arm, turns west opposite Windmill End Junction. To the north of this junction is the southern entrance of Netherton Tunnel. Both the north and south entrances of this tunnel are Grade II listed structures.

From Windmill End Junction, Line No. 2 continues towards the closed Lapal Tunnel. This area used to have a lot of factories. But most of them are gone now. They have been replaced by houses, small industrial buildings, and playing fields. At the northern end of Gosty Tunnel, a layby (a stopping place) marks where a tug boat used to be kept. This tug would pull barges through the tunnel. Beyond lies Hawne Basin. It was fixed up as a marina after it stopped being used for railway transfers in 1967. The end of the navigable canal is just past the basin entrance. Much of the rest of the route to the tunnel mouth can still be seen. The Lapal Tunnel Trust has done some restoration work. They have also worked on the section from the eastern entrance to the Worcester and Birmingham Canal at Selly Oak.

Points of Interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dudley Tunnel north portal | 52°31′24″N 2°04′44″W / 52.5233°N 2.0789°W | SO947917 | |

| Dudley Tunnel south portal | 52°30′04″N 2°06′03″W / 52.5012°N 2.1007°W | SO932892 | |

| Park Head Junction | 52°29′52″N 2°05′56″W / 52.4978°N 2.0990°W | SO933888 | Line No 2 meets Line No 1 |

| Delph Flight bottom lock | 52°28′32″N 2°07′24″W / 52.4756°N 2.1233°W | SO917864 | Jn with Stourbridge Canal |

| West end of Two Locks Line | 52°29′25″N 2°06′22″W / 52.4902°N 2.1060°W | SO929880 | |

| East end of Two Locks Line | 52°29′19″N 2°05′56″W / 52.4887°N 2.0990°W | SO933878 | |

| Lodge Farm Reservoir Cut | 52°29′04″N 2°05′33″W / 52.4845°N 2.0926°W | SO938873 | |

| Netherton Tunnel north portal | 52°30′55″N 2°02′58″W / 52.5153°N 2.0495°W | SO967908 | |

| Netherton Tunnel south portal | 52°29′36″N 2°04′09″W / 52.4934°N 2.0693°W | SO953883 | |

| Windmill End Junction | 52°29′30″N 2°04′13″W / 52.4916°N 2.0703°W | SO953881 | |

| Gosty Hill Tunnel north portal | 52°28′12″N 2°03′06″W / 52.4701°N 2.0517°W | SO965857 | |

| Hawne Basin | 52°27′28″N 2°02′23″W / 52.4577°N 2.0396°W | SO974844 | |

| Lapal Tunnel west portal | 52°26′44″N 2°01′43″W / 52.4455°N 2.0287°W | SO981830 | |

| Lapal Tunnel east portal | 52°26′39″N 1°58′35″W / 52.4442°N 1.9765°W | SP016829 | |

| Harborne Lane bridge | 52°26′37″N 1°56′33″W / 52.4435°N 1.9426°W | Proposed limit "in water" from Worcester & Birmingham | |

| Jn with Worcester & Birmingham Canal | 52°26′37″N 1°56′16″W / 52.4435°N 1.9378°W | SP043828 |

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |